Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of mortality in developed countries and one of the leading causes in developing countries. It is a progressive, dynamic, inflammatory, multicausal disease with both changeable and immutable factors, starting with endothelial damage with tissue repair characteristics. It begins in childhood, without symptoms, until the main complications occur (heart disease and stroke).

The need to prevent atherosclerosis in childhood is becoming increasingly evident due to the greater advancement of scientific knowledge about atherosclerosis; the possibility of obtaining serum cholesterol concentrations on an outpatient basis; and the increased awareness of the general population about cholesterol.

Changes in food composition made by the industry have had a major impact on the eating habits of children and adolescents, since excessive consumption of foods with a high amount of fat (

junk food ) generates an imbalance in the diet and requires nutritional educational measures to balance it.

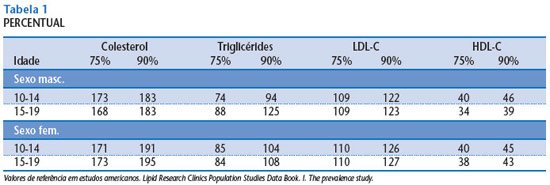

The reference values measured in several studies will be used as a basis.

CLASSIFICATION OF DYSLIPIDEMIAS

Dyslipidemias can be classified in two ways:

a) laboratory;

b) etiological.

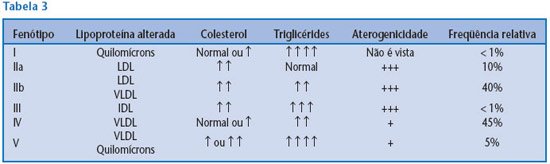

Laboratory – Uses the Fredrickson formula, which uses cholesterol, triglyceride (TG) and lipoprotein values (does not include HDLs).

Etiological – Dyslipidemias are subdivided into primary and secondary. Primary dyslipidemias are caused by a genetic defect. Secondary dyslipidemias are mainly caused by another disease (diabetes, obesity, hypothyroidism, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, etc.), medication use (diuretics, contraceptives, beta-blockers, etc.) and/or lifestyle (sedentary lifestyle, smoking, alcoholism).

Primary dyslipidemias are quite rare, the most important being familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), which is an autosomal dominant mutation of the specific gene for the LDL receptor on the short arm of chromosome 19. LDL receptors bind to LDL, facilitating its compression by endocytosis-mediating receptors and its release into lysosomes, where LDL is degraded and its cholesterol is released for metabolic use. Its characteristics are: ↑LDL, ↑TC, tendon xanthomas and atheromas. The homozygote is more severely affected, with a prevalence of 1:1,000,000 for homozygotes and 1:500 for heterozygotes.

CRITERIA FOR SCREENING DYSLIPIDEMIA IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

The screening criteria for dyslipidemia are related to family history, and all children and adolescents born to hypertensive, obese, or cardiac parents with a history of sudden death (before age 55 for men and 65 for women) and dyslipidemia should be screened.

All obese children with a BMI > 25 to 30 kg/m2

in relation to sexual maturity; signs of peripheral fat deposition (xanthoma, xantheloma, and arcus corneum) on physical examination; body composition with triceps and subscapular skinfolds > 90 percentile for age should be screened. The waist/hip ratio can also be used for screening (> 102 cm abdominal circumference for men and > 80 cm for women) with laboratory evaluation. Adolescent smokers and sedentary individuals should be screened.

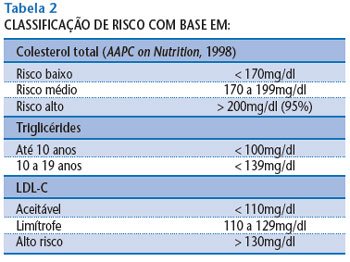

These assessment criteria can be performed by measuring total cholesterol (TC) or LDL cholesterol.

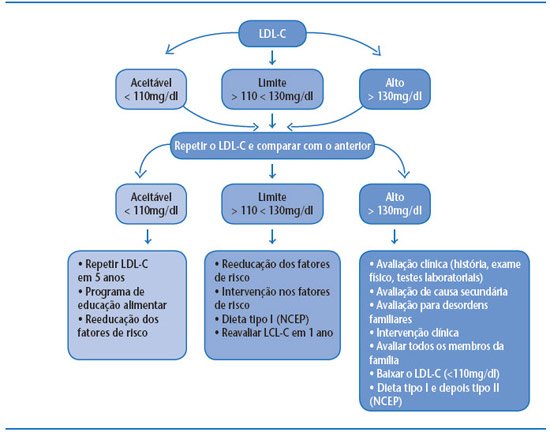

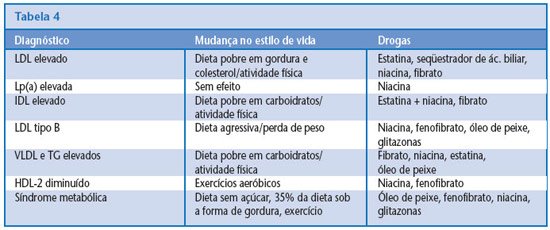

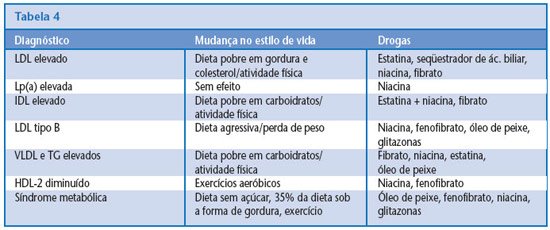

TREATMENT ROUTINE

Treatment of dyslipidemia should begin in early childhood. Children of parents with heart disease, hypertension, stroke victims, hypercholesterolemia and/or who died of sudden death should begin treatment at two years of age, with a healthy diet and physical activity. Medication should only be started after the age of ten and after the previous methods have been exhausted: strict diet and physical activity for at least six months.

In adolescents and adults, diet is always the first form of treatment and medication, the last.

1. Diet modification with healthy eating:

- lipids: between 20% and 30% of the average daily caloric intake;

- saturated fatty acids: < 10% of total calories; in case of higher risk, < 7%;

- polyunsaturated fatty acids: <10% of total calories;

- monounsaturated fatty acids: between 10% and 15% of total calories;

- cholesterol: < 300mg/day; in case of higher risk, < 200mg/day;

- carbohydrates: between 50% and 55% of total calories;

- proteins: between 15% and 20% of total calories.

2. Treatment of other risk factors: ↑ physical activity, ↓ smoking, ↓ stress, ↓ high blood pressure, diabetes control.

3. Medication: used in children over 10 years of age who do not respond to a diet to reduce LDL cholesterol (acceptable levels or a 15% decrease in the value). The risk/benefit ratio should be considered and medication should be instituted in cases of increased likelihood of familial dyslipidemia.

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of atherosclerosis in adults is closely correlated with dyslipidemia in childhood and adolescence. For this reason, it is extremely important to diagnose primary and secondary dyslipidemias at these stages of life.

The best form of treatment and prevention of dyslipidemias is diet therapy. The association with physical activity – feasible, supervised by a qualified professional and under medical supervision – should also be attempted. In a final phase, after unsuccessful attempts to control dyslipidemia through diet and physical exercise, drug treatment will be introduced.