From the earliest moments of life, eating is intertwined with emotions, symbolism, and socioeconomic and cultural influences. Growing up and eating involves establishing relationships, making choices, identifying or not with family or other people’s models and values, adapting well or badly to established standards, and living with habits, schedules, and different lifestyles. In adolescence, the need to establish new positions or break away from the family can also be expressed through emotional issues or conflicts in the area of sexuality that are transferred to eating. Eating too much or not eating at all can mean unconscious ways of satisfying deficiencies, refusing external controls, or being fashionable. And eating out can represent a new opportunity to create friendships, but also new food trends. In short, being different and still being the same as all your friends in the search for the here and now, an immediacy characteristic of adolescence.

Eating well is not the same as eating too much or too little. Taking care of a growing body means learning to choose foods better to maintain a nutritional balance between caloric gains and losses, with the necessary extras to ensure the increased growth rate, which is a characteristic of the pubertal growth spurt. The sensations of hunger and satiety and the differences between appetite, gluttony and voracity can serve to stimulate the adolescent’s own curiosity about nutrient groups and how to adapt their routine to achieve a healthy, balanced and palatable diet.

An imbalance in the balance between energy intake and expenditure at this stage has an impact on the health of adolescents and causes problems such as excess or loss of weight, acute and chronic malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, overweight, obesity, atherosclerosis, high blood pressure and an increase in the number of low-weight newborns among adolescent mothers.

The eating habits and exercise routines that are formed as adolescents gradually achieve independence can enhance or harm their lifestyles and health in adulthood. Nutritional deviations can also mean risky behavior and change the person’s trajectory from healthy to unhealthy; hence it is a problem that should always be investigated by the health professional who deals with adolescents and their families.

MANAGEMENT OF NUTRITIONAL GUIDANCE

The principles of nutritional guidance should be based on scientific and practical knowledge of the specific nutritional needs of adolescence and adapted to understandable terms of colloquial language that can be taught to each adolescent within the daily life of their social context.

The tools available for assessing food intake are forms in which intake is recorded over three or seven days, questionnaires on the frequency of food consumption, and data relating to the last 24 hours. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Data relating to the last 24 hours provide a fairly good estimate of energy intake and can be easily used during the consultation, but they obviously do not provide information on the variety from one day to the next and depend on the ability to recall the foods being asked about and the skill of the evaluator. Complementing this recall with a check on the frequency of food consumption solves some of these problems. The food diary covering three or seven days allows information to be collected prospectively, but it is time-consuming, both for the person completing it (the patient) and for the person analyzing it (the doctor). Motivation is an essential element in the reliability of the data, and time should be devoted to explaining to the adolescent or his/her parents how to fill out the forms correctly. Sometimes, many attempts are necessary before usable data are obtained(12,18).

It is also important to take into account the extra habits of weekends and special occasions such as the day before exams, birthdays, school holidays, sports competitions, etc.

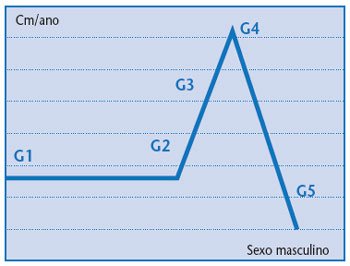

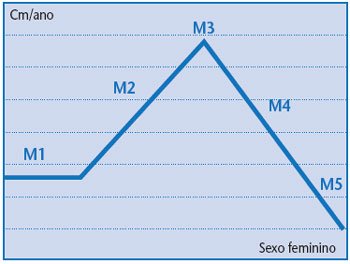

PUBERTAL VARIATIONS

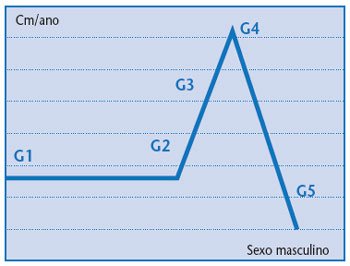

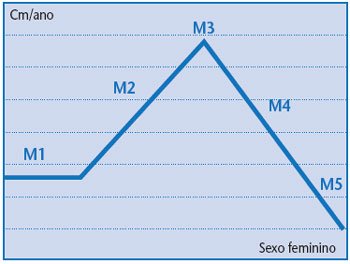

In order to assess nutritional needs in adolescence, it is necessary to know the wide variation of normal with regard to growth, which implies the great diversity of adolescents’ demands(1,3). At a certain point, chronologically variable between 11 and 13±2 years, the growth acceleration phase begins, followed by the deceleration phase until it stops completely. The increase in weight and height is due to the increase in the skeleton, muscle mass, fat, organs, with expansion of blood volume. The onset of these phenomena, their amplitude, the duration in each phase and their end vary greatly from individual to individual, even of the same sex, giving rise to different nutritional needs(9). It is known that the peak of nutritional needs for weight gain precedes the start of the pubertal growth spurt in height increase by four to six months, until it coincides with the period of maximum growth(21,24).

The differences between the sexes must also be taken into account. In females, growth acceleration begins two years earlier than in males, but growth ends earlier and the event is less extensive. In females, growth increases are mainly due to fat, and in males, muscle mass, which has a different impact on nutritional needs. Especially during the growth spurt, males need a greater intake of protein and energy, as well as a greater amount of iron per kilogram of weight than females. It was observed that, at the end of growth, there is twice as much fat and only two-thirds as much muscle mass in females compared to males. In females, the increase in nutritional needs during pregnancy and lactation deserves particular attention(2,25).

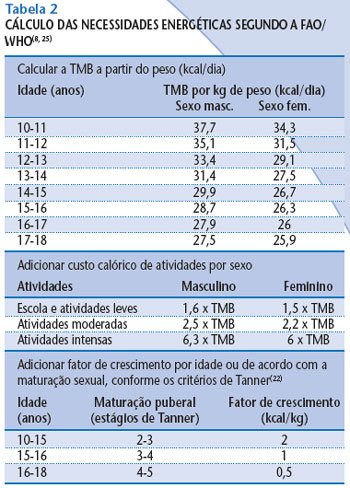

Sexual maturation, associated with the growth phases, is involved in nutritional diagnosis and prognosis, and is a determining factor in nutritional needs at each stage of adolescence. If an adolescent is seen in the prepubertal stage or stage 1, according to the criteria of sexual maturation(22), it is known that the growth spurt and maximum needs phase will be coming. If, through the maturation stage, it is perceived that the adolescent is close to menarche, one should carefully consider the nutritional needs and their relationship with this event in terms of body composition and fat percentage. On the other hand, when menarche has already occurred, the adolescent is probably in the growth deceleration phase, which implies a reduction in some nutrients in relation to the growth spurt phase and an increase in the intake of others, such as iron and folic acid(23). In males, the maximum growth rate generally occurs in an advanced phase of genital and pubic hair development, stages 3 and 4, coinciding with the maximum peak of nutritional needs.

Therefore, it is essential that at each medical visit or nutritional assessment, even when in community screenings, adolescents are evaluated with anthropometric data and nutritional indicators appropriate for a correct diagnosis(6,25). The most important data are:

- height;

- weight;

- calculation of height/age, weight/age, weight/height and body mass index indices;

- triceps and subscapular skinfolds;

- arm, thoracic and abdominal perimeters;

- sexual maturation according to Tanner criteria(22);

- use of recommended curves and tables (10, 15, 16, 20), as the choice of reference is important (19);

- periodic and longitudinal monitoring, whenever possible, every four to six months, or, in cases of nutritional risks, monthly or bimonthly.

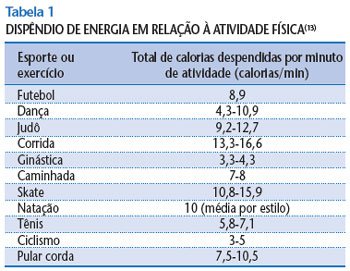

EXERCISE OR SPORTS

The greatest variation in terms of nutritional needs for adolescents is related to physical activities. To get an idea of the energy expenditure, some of these activities will be considered, as shown in Table 1.

It is always important to ask adolescents directly about their exercise habits, including the number of hours per week spent on weekdays and weekends, where they exercise (indoor or outdoor, exposed to sunlight, beach or street), access to water and/or other beverages and snacks, etc. Many adolescents frequently over-exercise, such as anorexics or gymnasts and dancers who “want to stay in shape after overeating,” and should also be carefully evaluated, as there are often additional emotional or stressful components associated with these over-exercising routines.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The imbalance between physical activity and food intake can lead to the onset of nutritional disorders such as malnutrition or obesity; in the latter case, adolescents often enter a vicious cycle, as their fat is not well accepted by themselves or their peers, which makes it difficult for them to participate in sports and outings, making them increasingly turn to food and inactivity. It is always important to take the opportunity to emphasize the contraindication of medications that can alter appetite, laxatives, diuretics, hormones or the use of anabolic steroids (pills or pumps), or drugs such as caffeine, marijuana, nicotine and others that can also impair the speed of pubertal growth, causing further hormonal imbalances.

In our environment, where the main concern is still pubertal delay due to malnutrition (5), obesity is also beginning to appear at all socioeconomic levels, being mainly linked to the excessive consumption of carbohydrates, which are cheaper and more accessible.

Caloric requirements during adolescence can be estimated in kcal/cm of height, varying with age, sex, sexual maturity, and adding the extra expenditures for daily activities. Maximum consumption for females should be estimated at around 2,500 kcal at the time of menarche, which occurs on average between 12 and 12.6 years of age, decreasing progressively thereafter to 2,200 kcal. For males, caloric intake requirements increase with the pubertal spurt to around 3,400 kcal around the age of 15-16, then decreasing to 2,800 kcal until the end of growth. Energy requirements can also be calculated using the equations for basal metabolic rate (BMR) with the addition of the growth factor and the activity factor by age group, according to FAO data(8).

NUTRITIONAL COUNSELING

Strategies for nutritional counseling of adolescents are based on the following principles:

1. Use a nonjudgmental and common-sense approach;

2. Recommend small increments and incremental changes;

3. Use a contract and incentive system that is agreeable to the adolescent;

4. Use simple and culturally acceptable terms;

5. Discuss food choices, amounts, and preparation methods;

6. Focus on the positive aspects of the diet rather than just the nutritious aspects; Explain that all foods can be eaten in moderation;

7. Be aware of the psychological, cultural, and socioeconomic aspects that influence diet and exercise patterns and facilitate positive support;

8. Encourage lifestyle changes for the entire family;

9. Avoid family conflicts that occur during mealtimes, especially during the day.

10. Do not underestimate or devalue the adolescent because of his/her body shape or size.

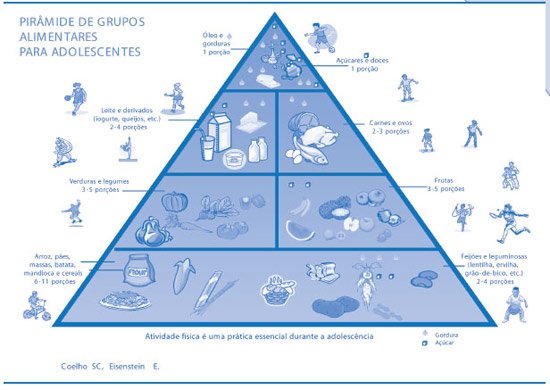

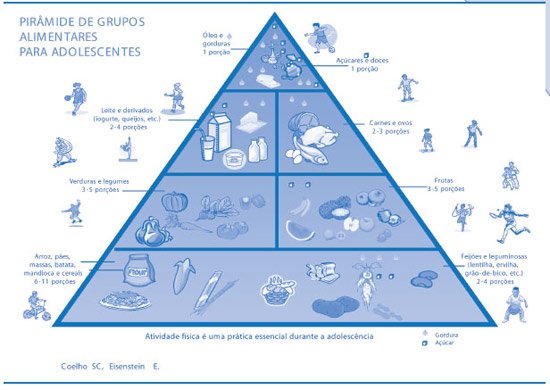

The macronutrient indications should follow the food groups illustrated in Figure 3, but always adapted to the most accessible foods in each region of the country and the time of year.

Figure 3

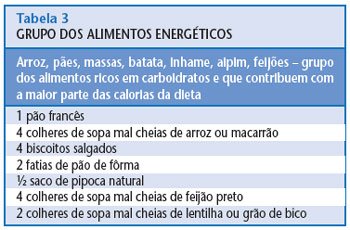

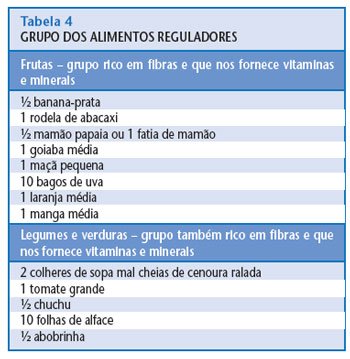

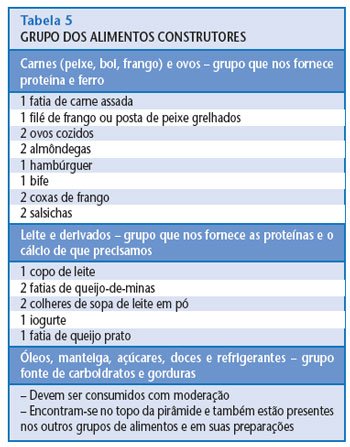

Examples of portions that can be used according to the food groups in the pyramid are presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Important tips for teenagers(6):

- eat at least one food from each group at each meal, according to the required portions;

- wash fruits and vegetables well before preparing them;

- try to eat all your meals at the right times and avoid snacking non-stop;

- breakfast is very important, don’t skip it in a hurry;

- drink at least five glasses of water a day, and six to eight glasses on hot or sunny days;

- Don’t forget to wash your hands before each meal and brush your teeth afterwards.

PROTEINS

They have a plastic function, enabling the essential growth and development of the organism, including tissue regeneration. The main sources of animal and vegetable proteins, such as meat, poultry, fish, milk, soy, grains and seeds, legumes and cereals, provide 20% to 25% of total calories and should be consumed in two to three portions a day(4).

CARBOHYDRATES

They have an energy function, ensuring metabolism and body temperature. They are the carbohydrates, sugars and starches found in cereals such as wheat, corn and oats, flour, rice, bread and pasta, vegetables and fruits, which constitute 50% to 55% of total calories, and should be divided into six to 11 portions a day.

LIPIDS

They have an essential caloric function performed by saturated and unsaturated fats found in oils, olive oil, butter, margarine, lard, bacon, sausages, creams, sauces, fried foods, and mayonnaise, and which can contribute 20% to 30% of total calories, and should be divided into one to two portions per day. Saturated fats should represent less than 10% of total calories, and cholesterol, less than 300 mg/day (17).

VITAMINS AND MINERAL SALTS

They have a function of regulating or regulating the rhythm of cellular and enzymatic reactions. The main sources are fruits, vegetables, whole grains, milk, seeds, meats, eggs, and grains, which should be part of three to five portions per day.

The daily requirements of most minerals double during adolescence, especially in relation to calcium, iron, and zinc. Restrictive diets and sports competitions affect bone mineralization, causing osteopenia, osteoporosis, amenorrhea, and delayed puberty. Of the total body calcium, 97% is contained in skeletal mass, and this proportion increases dramatically during the pubertal spurt, when the daily calcium deposition is almost double the average increase for the entire growth period, and is higher for boys. Calcium content is height-dependent, and therefore a tall adolescent in the 95th percentile may require 36% more calcium than a short adolescent in the 5th percentile. In females, this difference is about 20% between taller and shorter women. Approximately 20% to 30% of the calcium ingested is absorbed, so an average intake of 1,200 mg of calcium per day is recommended, depending on the needs of each adolescent.

Likewise, the need for iron increases with the growth of muscle mass, blood volume and respiratory capacity, in addition to menstrual losses and increased exercise. The iron content of the diet is also quite variable, from 4 to 6 mg/kcal. Therefore, adolescents with deficient eating habits will not be able to receive the total amount of iron they need during the pubertal growth spurt and with the onset of menstruation, calculated at around 15 to 18 mg per day.

Zinc has been associated with growth retardation, hypogonadism, decreased taste sensation and hair loss in adolescents with anorexia and also in athletes and pregnant women. The need for mineral supplementation will depend on the variety and quality of the diet, especially during the pubertal growth spurt.

Vitamin requirements increase due to increased anabolism and energy expenditure during puberty. Other factors also contribute to this increase, such as physical activity, pregnancy, oral contraception and chronic diseases. The increased need for vitamins A, C and D and the B complex is progressively greater during the pubertal growth spurt, with cellular differentiation and bone mineralization(14).

Folic acid supplementation, 400 mcg/day, should be routinely prescribed for sexually active or pregnant adolescents and those of low socioeconomic status. Vitamin deficiencies are more frequent in adolescents who do not have the habit of daily intake of fruits, vegetables, milk or cereals(11). WATER

Water

, fruit juices, coconut water and other sources of liquids and hydrants should be consumed, on average, in a proportion of four to six glasses per day. On hot days, after going to the beach, swimming pool, sun activities or exercising and sports, increase the dose to six to eight glasses per day (2 liters). Alcoholic beverages, energy drinks or anabolic supplements should always be contraindicated. Milk, an important source of calcium, proteins and vitamins during this growth phase, should be part of the daily menu with two to three glasses per day, in addition to one to two servings of dairy products and dairy products, such as cheese, curds, yogurt, ice cream, puddings and desserts or sandwiches for snacks. Natural milk can be replaced by skimmed or fat-free milk, if necessary for weight control.

There is no standard diet that works for all adolescents. It is important to adapt all groups of nutrients to the different stages of the pubertal growth spurt, and, according to daily activities and different lifestyles, divide the diet into three meals and two to three snacks per day, balancing daily intake and expenditure, without overdoing it on the weekends.

FAMILY AND SOCIAL SUPPORT

The family environment, with its socioeconomic structure, dynamics and cultural characteristics, provides support for all these individual factors. Family conditions determine, even before adolescence, the formation of eating habits that will undergo, to a greater or lesser extent, modifications resulting from the factors mentioned above.

Meeting the nutritional needs of adolescents is therefore a complex problem that involves an individual and environmental approach. The preventive aspect must always be present when caring for children and pre-adolescents by promoting the formation of appropriate family habits. One should try to adapt the adolescent’s eating conditions, providing adequate qualitative and quantitative food availability. One should try to encourage snacks and school meals, which serve as a complement to daily needs. In cases of overweight or obese adolescents, these snacks should be replaced by fruits, fruit juices, cereal bars, natural sandwiches, etc., instead of soft drinks, chips, cookies, etc. When it comes to weekends and parties, it is important to guide the adolescent so that he avoids excesses, especially with alcoholic beverages and snacks, and knows how to make substitutions to compensate the following day. The adolescent must learn to recognize his growth characteristics and relate them to nutrition and well-being.

The aspects of psychosocial development should be considered carefully, avoiding rigid guidelines or, on the contrary, the absence of clearly established guidelines and limits to improve the adolescent’s diet. Whenever possible, group activities and educational lectures held at schools, clubs and on outings should be emphasized, both for the adolescents themselves and for parents and educators.

It is important that the family is aware of and accepts the changes in the adolescents’ eating habits so as not to create situations of further conflict in this area, which are often used to hide or disguise emerging problems related to sexuality or the lack of dialogue between parents and children.

The main prerequisite is that the professional is able to provide guidance, not only based on his or her knowledge of the various nutrients, but mainly taking into account the unique characteristics of this age group.

The attitude should basically be one of exchanging information, with freedom of choice without impositions. The adolescent should be involved in the process that may result in changes in eating habits and, to this end, ready-made formulas or the single model generally originated from the adult’s point of view should be abandoned. Within this approach, the basic premise will be based on the fact that it is easier to make the filling of a sandwich suitable than to replace it.

CONCLUSIONS

Puberty is an intense period of growth, with sexual and physical maturation increasing the need for all nutrients. Adolescence itself is a phase of transition and search for new patterns and alternatives in life. For this reason, it is also the best time to emphasize and invest in prevention and health education programs to spread new eating habits among young people, as they are the best promoters of social change in a community. The food security of a population also depends on the collective effort of parents, health and education professionals, as representatives of society in general, in addition to the government and public policies regarding nutritional issues.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3