INTRODUCTION

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the second most common group of rheumatic diseases in childhood and adolescence in underdeveloped countries, where rheumatic fever is very prevalent, unlike in developed countries, where it is rare and JIA is the main cause of illness in this age group. JIA is a chronic arthritis that begins in children under 16 years of age and can affect one or more joints. Its diagnosis is predominantly clinical, and infectious, neoplastic, hematologic and other rheumatologic diseases should be ruled out.

Juvenile spondyloarthropathies (JSA) are being recognized and diagnosed more frequently, and this group includes juvenile ankylosing spondylitis (JAS), Reiter’s syndrome and other reactive arthritis, and arthropathies associated with inflammatory bowel diseases(1). Most of these diseases meet the criteria for arthritis associated with enthesitis in the new JIA classification(2), since enthesitis is a frequent manifestation of these diseases in the pediatric age group (Table 1).

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) appears as the end of the spectrum of a disease whose onset is represented by syndromes consisting of peripheral arthritis, axial involvement, enthesopathy

(involvement of the entheses, as will be reported below) and/or extra-articular manifestations, with absence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor, but with an increased frequency of the presence of the HLA B27 antigen(3). One of the controversial issues in its natural history is the percentage of children and adolescents with these previous complaints, often vague or frusto, frequently similar to undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies, who will progress to AJS. Peripheral joint involvement consists, in most cases, of an asymmetric oligoarthritis involving mainly the lower limbs. Axial involvement occurs later, appearing as low back pain with inflammatory characteristics, that is, it improves with movement and worsens with rest, in addition to sacroiliitis, which manifests as pain in the gluteal region. Radiological changes in AS generally do not appear in adolescence. Laboratory changes such as normocytic, normo or hypochromic anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, increased acute phase proteins and hypergammaglobulinemia are associated with disease activity (4,4A,5,5A).

ENTHESOPATHY

Enthesitis, that is, inflammation of the entheses, which are the final part of the tendon that connects it to the bones, occurs mainly in the lower limbs: metatarsal heads, base of the fifth metatarsal, insertion of the plantar fascia and Achilles tendon in the calcaneus, anterior tuberosity of the tibia, 10, 2 and 6 o’clock positions of the patella, greater trochanter, pubic symphysis, iliac crests and anterior superior iliac spine. The limitation of spinal movements is assessed by the full realization or not of the movements of the different segments of the spine and by the sequential measurement of the anteversoflexion of the same (modified Shober test for children)(6,7).

The initial drug treatment for enthesitis and AJS is done with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to suppress pain and inflammation, allowing physical therapy exercises to be performed. The most frequently used drugs are acetylsalicylic acid (80-100mg/kg/day in three to four doses), naproxen (10-20mg/kg/day in two doses), and ibuprofen (20-40mg/kg/day in three to four doses), but indomethacin (1-3mg/kg/day in two to four doses) seems to provide the best response in spondyloarthropathies. Sulfasalazine (SSZ) at a dose of 40-60mg/kg/day also seems to be a good option for the treatment of AJS, although it does not seem to act as a disease-modifying drug in relation to the prevention of spinal ankylosis or joint erosions. The use of corticosteroids orally, intra-articularly, directly into the entheses or topically (ophthalmological use) may eventually be necessary, as may other immunosuppressive drugs and biological agents such as anti-TNF (infliximab and etanercept)(7A). Early physical and occupational therapies are extremely important in maintaining or recovering movement, muscle strength, good posture, and functional position of the joints involved in these patients. We must not forget psychosocial and educational support for adolescents and their families, in addition to professional guidance.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Joint involvement in inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis or regional enteritis) can be defined as non-infectious arthritis, occurring before or during the course of the disease in approximately 20% of cases(8). It is considered the most frequent systemic manifestation. It appears to have a higher incidence in children with more extensive disease in the digestive tract. Joint involvement may be peripheral or axial, the latter being less frequent and usually related to the presence of the HLA B27 antigen. There is a predominance of males (4:1) in forms with axial involvement, but females predominate (1.2:1) in forms that present with peripheral arthritis. There is a familial association between inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and other ACEs. Sacroiliitis may be asymptomatic, but frequently manifests with pain in the gluteal region, and may be accompanied by inflammatory low back pain and enthesitis. Axial involvement is not related to the activity of the underlying disease. Peripheral involvement usually occurs as an asymmetric oligoarthritis of the lower limbs lasting four to eight weeks and which may recur in flare-ups, generally associated with the activity of the underlying disease. Other musculoskeletal manifestations include polyarthralgias, myalgias and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. The mucocutaneous lesions most frequently associated with IBD are oral ulcers, erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, linked to peripheral joint involvement. Gastrointestinal and constitutional symptoms (diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fatigue, fever) usually precede the joint condition by years and, more rarely, the involvement is simultaneous or preceded by arthritis. Acute uveitis rarely occurs. Laboratory tests show significant anemia, hypoproteinemia, elevated acute phase proteins and negative rheumatoid factor and ANA. Control of the underlying disease usually leads to improvement in the peripheral joint condition, therefore the use of corticosteroids or sulfasalazine is indicated. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) may eventually be used until the intestinal inflammation is controlled. The indication for colectomy is associated with the intestinal disease, and not with the intention of neutralizing the joint involvement. Since the axial involvement is independent of the intestinal inflammatory activity, even with control of the underlying disease, these symptoms may persist, and then NSAIDs and physical therapy are indicated(6,8).

REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

Reactive arthritis is that which generally occurs one to four weeks after infection, although the agent responsible for the initial infection is not present in the joints. The organism that initiated the immunological process can often be identified, either serologically or by cultures of secretions from initially affected organs. Occasionally, joint involvement may be simultaneous or even precede the acute symptoms of some infectious diseases. The classic name Reiter’s syndrome (RS) is reserved for reactive arthritis that occurs with the triad of arthritis, conjunctivitis and urethritis, but the current trend is to call these conditions simply reactive arthritis. As in adults, there is a predominance of cases in males (6).

In the pediatric age group, reactive arthritis is more frequently associated with gastrointestinal infections by gram-negative bacteria, such as

Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, Campylobacter jejuni, Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (9). Reactive arthritis related to sexually transmitted diseases (

Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealiticum ) is less frequent in children, but can be observed in sexually active adolescents. The clinical picture of the joints is generally acute, very painful, but self-limited, manifesting as asymmetric oligoarthritis, mainly of the lower limbs, and enthesitis. Sometimes the joint picture may be recurrent or persistent. Axial involvement, when it occurs, may initially manifest due to enthesitis in the spine, although evolution as AS does not usually occur in childhood, only later. The laboratory tests are nonspecific. Most children respond well to NSAIDs. Occasionally, other drugs such as corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, methotrexate or azathioprine may be used. There is no evidence that antibiotic therapy in children, in cases related to enteropathogens, alters the course and evolution of the joint picture. In adolescents, regarding sexually transmitted diseases, antibiotics seem to alter the acute picture of reactive arthritis, but there is no data on their influence on the long-term course of the disease. The course of reactive arthritis and RS is usually self-limiting and the prognosis is good(9,10).

PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS

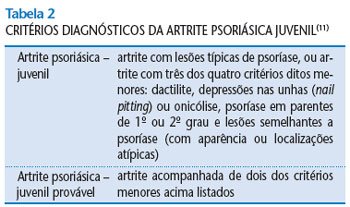

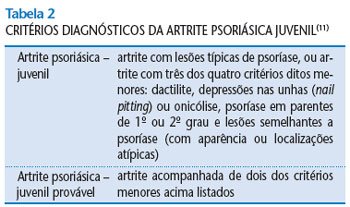

Juvenile psoriatic arthritis (JPA), defined as chronic arthritis, appears before the age of 16 and is associated with psoriatic skin lesions. Since the joint symptoms can sometimes precede psoriasis by years, these children are often misdiagnosed with JIA or JEA. To facilitate early identification of the disease, even in the absence of skin lesions, Southwood et al. (1989) proposed criteria for definitive or probable diagnosis, which became known as the Vancouver criteria(11) (Table 2). Although JPA is classically classified in the group of spondyloarthropathies, it is currently considered a separate entity, as seen in the new classification of childhood idiopathic arthritis.

Adult psoriatic arthritis is classically subdivided according to its mode of onset into asymmetric pauciarticular (most common), symmetric arthritis (similar to RA), arthritis with predominance of distal interphalangeal (DIP) involvement, axial involvement and mutilating arthritis. Children and adolescents have a similar relative distribution to adults, although they present more overlap in relation to the different subtypes. The most common form of onset is also asymmetric pauciarticular of large or small joints, which, over its course, will become polyarticular in most cases. Treatment consists of the use of NSAIDs, corticosteroids and/or methotrexate, with other immunosuppressants occasionally being indicated(12).