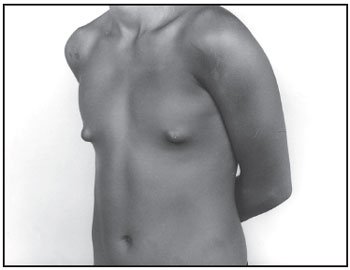

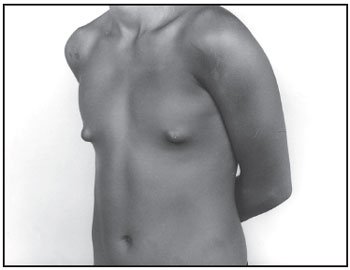

Pubertal gynecomastia is the growth of glandular tissue in the male breasts during the period of sexual maturation. It should be distinguished from pseudogynecomastia, which causes fat accumulation in the subareolar region. Accurate diagnosis, counseling and treatment (if necessary) are essential to alleviate the feeling of deformity and lack of sexual attractiveness, which often occurs at the very moment when self-image is developing. Sensitively determining the best time to intervene is crucial to optimizing aesthetic, functional and psychological results. This prevents puberty from passing without intervention and the consequences from lasting a lifetime (Figure 1).

Figure 1

There are no data in the national literature on the subject. Foreign studies report 19.6% of gynecomastia in boys aged 10.5 years, with a peak prevalence of 64% at 14 years, decreasing thereafter(6). The average age of onset is 13 years and 2 months. Approximately 4% of adolescents will have severe enlargement (>4 cm in diameter), which will persist into adulthood. Still on residual gland, a study found a palpable 2 cm breast in 17% of boys aged 19 years or younger and in 33% of those aged 20 to 24 years. Gynecomastia is also common in the neonatal period (60% to 90%) and between 50 and 80 years in a man’s life.

RELATIONSHIP WITH PUBERTY

Gynecomastia appears most frequently at the beginning of the pubertal growth spurt, and it is important to correlate it with the stage of sexual maturation according to Tanner’s criteria (1962):

- genital stage I: 20%;

- genital stage II: 50%;

- genital stage III: 20%;

- genital stage IV: 10%.

CLINIC

When obtaining the clinical history of gynecomastia in adolescents, it is important to assess the age of onset and duration, in addition to palpating one or more subareolar nodules, of equal or different diameters, which may be asymmetrical and cause pain. The increase is bilateral (77% to 95%), concentric and under the nipples, and may be concomitant or sequential, although eccentricity is less common. The consistency is elastic, identical to that of the female breast, or fibrous in more prolonged cases. It is important to observe whether the consistency is hardened, whether the nipple is retracted by the mass and whether the skin has an altered texture, checking for bloody nipple discharge. In these cases, it is necessary to rule out breast cancer. It is important to assess, from the beginning of the consultation, the stage of sexual maturation and ask about the use of medications or any substance, be it alcohol, marijuana, anabolic steroids or others. Breast enlargement can be classified as: class I, one or more mobile subareolar nodules; class II, breast nodule(s) extending beyond the perimeter of the areolas; class III, breasts similar to female breasts (Tanner III).

Previous history of testicular trauma, orchiopexy and other surgeries, viral orchitis, liver disease, kidney disease and pituitary tumor, among others, should be questioned, in addition to checking for sexual dysfunction and even infertility.

In the family, questions should be asked about gynecomastia in the father, premature thelarche in the sisters and other genetic diseases affecting sexual development in relatives.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Assess the general health and nutritional status of the adolescent, observing physical stigmas of liver disease, thyroid or kidney disease, presence or absence of eunuchoid habit, voice timbre and hair distribution. Examination of the testicles is mandatory, observing size, consistency, nodules or asymmetry. The breast examination is performed with the patient in the supine position, in front of the examiner, who will pinch the mass between the thumb and index finger, gently pulling it towards the nipple and bringing the fingers together. In the case of gynecomastia there will be a mobile nodule and a firm or elastic consistency, concentrically distributed under the nipple in most cases. It may be eccentric and asymmetrical in a smaller number of cases.

ETIOLOGY

It can be physiological, pathological or idiopathic (Table 1). The first occurs due to transient hormonal changes and influences in the newborn, during puberty and aging. Pathological gynecomastia can be caused by decreased or absent testosterone action, increased estrogen production or increased conversion of androgens to estrogens. Pathological conditions associated with gynecomastia include congenital anorchia, Klinefelter syndrome, testicular feminization, hermaphroditism, adrenal carcinoma, liver disease and malnutrition. Many pharmacological agents can cause gynecomastia (Table 2). Some men have increased aromatase activity within fibroblasts, suggesting that aromatization of androgens within breast tissue could be responsible for idiopathic gynecomastia(3). It has also been suggested that patients with protracted neonatal gynecomastia would be more susceptible to persistent pubertal gynecomastia, supporting the concept that breast tissue is inherently more responsive to estrogenic stimulation in some men.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The breast tissue of men and women is similar at birth. During puberty, in boys, it demonstrates mesenchymal, ductal and periductal proliferation, regressing and atrophying as testicular androgens are secreted in increasingly higher levels. Estrogens stimulate ductal proliferation and androgens antagonize this effect. At the beginning of puberty, there is an imbalance in this antagonism. Since estradiol levels increase only three times their childhood basal value, while testosterone, at the end of puberty, reaches 30 times childhood levels, the estradiol peak is reached much earlier, causing a relative increase in estrogen and thus stimulating gynecomastia. Aromatase transforms testosterone into estradiol and androstenedione into estrone, and plays a fundamental role in estrogen synthesis in men. Adult testes produce only 15% of circulating estradiol and less than 5% of estrone; the remainder is produced in extraglandular sites through aromatization(6). Because of this, significant increases in extraglandular tissue, as in obesity, result in elevated circulating estrogens.

DIAGNOSTIC CONDUCT

In healthy adolescents at the beginning of the pubertal growth spurt who present with firm or elastic, subareolar, bilateral breasts, without drug use or evidence of other pathology, the probable diagnosis is pubertal gynecomastia. Laboratory tests are not necessary, and the adolescent should be assured that the breast will disappear within a period of six months to one year and periodic assessments should be scheduled for individualized monitoring. If there is significant increase (≥4 cm), with significant psychological repercussions, and no evidence of spontaneous regression, treatment should be considered. If drugs are being used, they should be discontinued and the patient reevaluated in one month. After this period, the condition should begin to regress. If pubertal gynecomastia, drug use, and liver or kidney disease are ruled out, then an endocrinological diagnostic study is desirable. It is important to measure human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone, and estradiol, as well as other hormones, such as thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and prolactin. If necessary, consider testicular ultrasound, computed tomography, or adrenal magnetic resonance imaging. If breast tumors are suspected, perform a mammogram and fine-needle biopsy. Chest X-rays and computed tomography of the chest and abdomen should be performed to screen for tumors that produce HCG and other hormones.

TREATMENT

Most adolescents with pubertal gynecomastia, particularly mild to moderate degrees, do not require treatment. Treatment should only be ensured that the process is temporary, with complete regression almost always occurring within six months to a year. A physiological explanation of the process helps with understanding and reduces anxiety. Adolescents need clarification and emotional support, and mental health monitoring may be necessary. It is important to be aware of problems at school, as the affected student may be humiliated. Sometimes it is important for the health team and the school to work together to ensure that the young person does not fail a school year. New appointments should be scheduled to assess the progress of the process on an individual basis, always taking into account the disturbance in self-image and the psychosocial repercussions.

Several drugs can be used to treat pubertal gynecomastia, but none are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). There are few studies of these drugs in adolescents, such as danazol, tamoxifen, clomiphene, dihydrotestosterone and testolactone, the latter two not being available in Brazil. Dihydrotestosterone is non-aromatizable and can lead to a reduction in breast volume in 75% of patients, with 25% having a complete response (Kuhn, 1983). Breast pain disappears in one to two weeks, and no side effects are observed. Danazol has been studied, and some results indicate the disappearance of gynecomastia in 23% of patients and in 12% of those taking placebo. The side effects of danazol are: weight gain, edema, acne, cramps and nausea, which has limited the use of this treatment.

Both clomiphene and tamoxifen have been used for their antiestrogenic effects. The first was effective in 64% of patients at a dose of 100 mg per day for six months. The second reduces volume and pain without side effects at a dose of 10 mg twice a day. Given the safety of the drug, it is reasonable to try a three-month course in patients with recent-onset painful gynecomastia.

Testolactone is an aromatase inhibitor that has been used in a small number of patients with pubertal gynecomastia at a dose of 450 mg per day for up to six months without side effects(3).

If drug treatment is ineffective, or if the gynecomastia has been present for several years and no longer responds to antiestrogenic drugs, or if it compromises the patient’s physical, psychological and social well-being, the glandular tissue should be surgically removed.

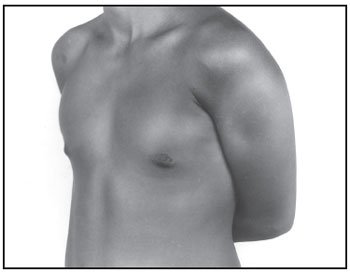

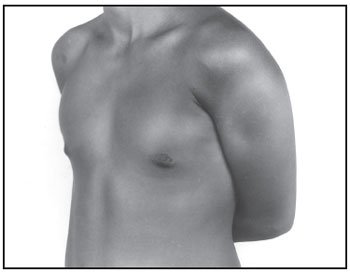

Surgical resection or subcutaneous mastectomy may be the choice, with different techniques available depending on the degree of gynecomastia. Liposuction has been used to complement mastectomy, or even in cases where lipomastia is the isolated procedure of choice (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

Gynecomastia is a common finding during puberty and can cause several problems, affecting adolescents’ communication with those around them in different ways. Initially, the professional who most often comes across this manifestation is the doctor, but it is important that all those who are in contact with adolescents are alert to the occurrence of gynecomastia. Parents, educators, physiotherapists and physical education teachers in different sports, clubs, gyms, camps and sports clinics, should be familiar with this possibility, which, once identified, should be referred to the health service. What is often observed is the existence of a practice of not considering gynecomastia a problem, always thinking of it as something benign in its biology, with a favorable evolution to disappear, without taking into account, even because the adolescent hides it, how much this problem can mark the young person’s life. At school, it can interfere with academic performance; In the sexual sphere, it includes dating as a consequence, causing a feeling of rejection, which can be stimulated by the group members or self-imposed by fear of other people’s reaction to their problem, which is felt as a deformity. Another aspect is the interruption of sports and other activities. It is also worth noting that the diameter of the breast increase, considered embarrassing for one young person, goes completely unnoticed by another, and it should be valued that this increase is felt only by the adolescent who is being treated.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3