INTRODUCTION

The first sexual relations involving genitals usually occur during adolescence, and these have currently occurred at earlier ages and with a greater variety of partners, contributing to the increase in the occurrence of unexpected pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). STDs favor HIV infection, and the largest number of AIDS cases reported to the Ministry of Health are in the age group between 20 and 34 years, with sexual intercourse being the main means of transmission(4). Since the latency period of the disease is long, reaching 11 years, we can infer that most carriers must have become infected during adolescence.

Biological, psychological, social, and other factors interfere with sexuality. The young age of menarche/semenarche may favor earlier sexual initiation, since puberty hormones intensify sexual desire. In relation to psychological development, adolescence is a phase in which sexual identity is defined, in which there is experimentation and variability of partners(13). Abstract thinking, which is still incipient, makes young people feel invulnerable, lacking self-protection attitudes and exposing themselves to risks without foreseeing the consequences. Despite information about STDs, this does not result in effective actions to protect health. According to some studies, the family plays an important role in the sexuality of children through the transmission of values and attitudes(8). A study conducted with adolescent mothers revealed that not having a father who is effectively present, especially from an emotional point of view, is a risk factor for early sexuality. Young people who did not receive affection and care from their family early on engage in unprotected sexual relationships, perhaps to fill an emotional void(12).

From a social point of view, group influence, economic level, low education level and violence in its various contexts are related to the young age at first sexual relations, the number of partners and protective attitudes against STDs. Early sexual activity is not an isolated phenomenon and frequently occurs when there is involvement with drugs or alcohol and, sometimes, delinquent behavior(3). Social models of male and female sex also exert a powerful influence on young people, increasing their vulnerability to health risk factors.

The objective of the present study was to understand the sexuality of adolescents treated at the Center for Studies on Adolescent Health (NESA) and to verify possible factors associated with the onset of sexual activity with genital involvement.

POPULATION STUDY AND METHOD

This is an observational, cross-sectional study, whose target population was adolescents who sought medical care at NESA between August 2001 and July 2002. NESA is a public institution whose outpatient clinic serves adolescents between the ages of 12 and 19, most of whom belong to low-income classes, in a variety of specialties.

The study sample was a convenience sample, and participants were randomly selected (non-probabilistic) from among the patients waiting in the waiting room. The reason for the consultation and whether or not the adolescent was sexually active were not known in advance. The instrument used was a semi-structured interview that followed a previously established script and was tested in a pilot study with 20 young people not included in this sample. All interviewers received training from a single researcher before going into the field, and weekly research team meetings were held to check the data. The validity of the information was ensured in several ways. When there was doubt as to the veracity of the interview, the participant was excluded from the sample. In addition, approximately 5% of the interviews were repeated by another interviewer who obtained the same answers. These procedures were carried out in order to guarantee internal homogeneity.

The adolescents were interviewed alone, after informed consent. The interviews were conducted successively over a period of twelve months. As a criterion for inclusion and selection of this sample, we intentionally prioritized the STD, gynecology and urology outpatient clinics, where the possibility of sexually active patients was greater. At the same time, adolescents were interviewed at the other outpatient clinics.

The interview schedule, composed of three parts, included open and closed questions. The first part investigated personal data such as age, family income, education, work, exercise, use of alcoholic beverages, tobacco and other drugs. School delay was considered to be a gap greater than two years in relation to the expected age for the grade attended. Regarding exercise, it was classified as regular when performed at least three times a week. Alcohol and drug use was categorized as

once in a lifetime, in the last month, and six times or more in the last month .

In the second part of the interview, we asked in detail about the family: who they live with, their opinion of their father and mother, their relationship with each parent and with each other. The questions were open-ended and the interviewer was careful not to suggest the answers, such as asking if their father was a good person.

The third part investigated the adolescent’s sexual and pubertal history, as well as the time of menarche/semenarche and first intercourse. Next, we asked about the occurrence of homosexual relations, prostitution, sexual abuse and pregnancy. The last questions were about the number of partners and the use of condoms.

In the statistical analysis of the structured responses, we used the chi-square test with a significance level of 95%. The statements to the open-ended questions were read and reread exhaustively, and from this, categories were constructed, then quantified and statistically analyzed.

The research project was previously evaluated and authorized by the Research Ethics Committee of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital. The informed consent form was signed before the interview.

RESULTS

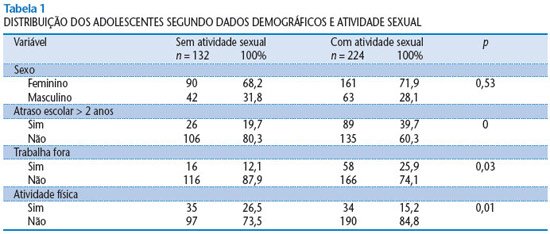

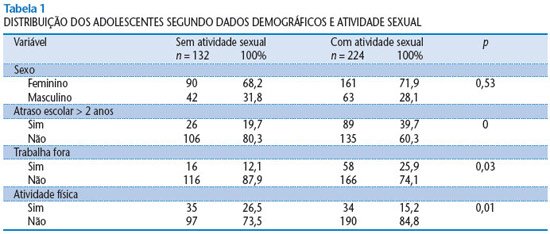

We interviewed a total of 356 adolescents in an environment where privacy was guaranteed. The average length of each interview was 25 minutes. Among the interviewees, 132 had not yet initiated sexual activity and 224 were sexually active, of which 109 were STD carriers and 115 were non-carriers. Boys comprised 29.5% of the sample and girls, 70.5%. The predominance of females occurred due to the large volume of care provided by the gynecology outpatient clinic. The percentage of men and women in each group was similar. The average age of the non-sexually active (15 years and 11 months) was ten months younger than that of those who had already initiated sexual activity (16 years and 9 months). Family income was similar in both groups (four minimum wages). Regarding education, there was a statistically significant relationship between being behind in school and no longer being a virgin. Paid work outside the home was significantly more frequent among the sexually active. Regular physical activity was found predominantly among those who had not yet had their first sexual relations. The distribution of personal demographic data can be seen in Table 1.

The categories

of alcohol consumption in the last month and six or more times in the last month were computed together, as well as

once in life and

never . Regarding tobacco and drug use, we categorized them only as yes or no, regardless of the frequency of consumption. We observed that tobacco, alcoholic beverages and other illicit drugs were used in a significantly higher percentage among sexually active adolescents than among non-sexually active adolescents, as can be seen in Table 2.

In the analysis of family data, we created two classes of family: biparental and non-biparental, according to whether or not the interviewee lived with both parents. There was a statistically significant relationship between virginity and biparental family. The responses about parents were categorized as father/mother

with qualities, with defects or

not informed , and the adolescent’s relationship with parents was categorized as

good, average, terrible or

not related . We observed a significant relationship between the variables

having a father/mother with qualities and

a good relationship with children and

not being sexually active . These data are presented in Table 3.

In the survey on puberty and sexuality, we observed that the average age of menarche/semenarche among those who had not yet had their first sexual relations was lower than that of those who were sexually active (11 years and 6 months and 12 years and 4 months, respectively). The rate of sexual abuse among those who were sexually active was 21.4%, and in the other group, it was 3%. There was a statistically significant relationship between having suffered sexual abuse and already being sexually active. Most of the interviewees in both groups had already had some type of sexual orientation, however, among those who were not sexually active the percentage was significantly higher (80.4% and 92.4%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This study used a convenience sample that cannot be generalized. However, our results are similar to those of other studies(1, 6) and can serve as an aid to understanding issues of sexuality in adolescence.

One of the main concerns of health professionals who treat adolescents is to understand why some of their clients have their first sexual intercourse under protected conditions and others do not, and, within the current scenario in which the age of sexual intercourse is decreasing and the number of STDs and teenage pregnancies is increasing, to know what to do to promote the sexual health of this population.

We live in an eroticized society, where young people receive mixed messages about what is good or bad in relation to sex. There is a negligent social permissiveness. In general, sexual activity begins without sufficient clarity between what is desired and the influence suffered by peers and society. Through the media, adolescents are encouraged to

have sex early. On the other hand, religious communities condemn sexual activity before marriage. Even among non-believers, virginity is still valued for women(2). Hegemonic models of sex associate, among men, sex and pleasure, and, among women, sex and procreation. Men are expected to begin their sexual life very early (in adolescence) and to have several sexual partners inside and outside of marriage. As for women, they are expected to abstain from sex before marriage and be faithful to their husbands afterwards.

In the present study, we observed some factors associated with the onset of genital sexual activity, including low education, use of tobacco, alcoholic beverages and drugs, and a history of sexual abuse. As for virginity, it was related to families in which both parents are present. These results are corroborated by other national and international studies(10,11).

Since the 1980s, efforts have been made to include sexual orientation content in the elementary and high school curriculum, with the aim of enabling young people to avoid the undesirable consequences of early and irresponsible sexual activity. However, this has not resulted in a concrete reduction in sexual activity in adolescence and its harmful consequences. Simply providing information is insufficient. However, in our research, we observed that the sexually active group reported having received significantly lower rates of sexual orientation when compared to the non-sexually active group.

Among the factors associated with the initiation of genital sexual activity in adolescence, we would like to highlight two: family and the use of legal or illegal drugs. A ten-year longitudinal study conducted with 203 virgin adolescents, whose objective was to evaluate the transition of those who had had sexual relations, revealed that the group of virgins had a higher rate of conversation with their parents(5). Another study shows a strong association between virginity and a structured family(7). Regarding drug use, we noted great tolerance on the part of society. Smoking and drinking alcohol are normal during adolescence. Families are not surprised to see a drunk child come home from a party or a nightclub.

We need to reverse the current situation of premature engagement by many adolescents in unprotected sexual activity, which has led to unwanted pregnancies and STDs. In addition to the importance of raising awareness among the population about the harm caused by early sexual relations, the work of health professionals must enable adolescents to negotiate safe and pleasurable sexual practices, respecting their partners and being respected. Sexuality needs to be part of a space for exchange, not only as an eroticization of sexual relations per se, but, above all, as a place for the two to manage sexuality, pleasure and risk; a form of

savoir-être and

savoir-faire required for the exercise of sexual freedom through the “prudent use of pleasures”, in the words of Rudelic-Fernandez(9).

In listening to adolescents, supporting families, providing educational work in schools, training young health promoters, training professionals, and, ultimately, in the various practices that support research, it is important to highlight the need for a truly effective focus on family relationships. We consider it extremely important that all sexuality guidance and health promotion work include the family and the prevention of alcohol and drug use. Strategies need to be created to encourage greater communication between parents and children.

In indicating avenues for further research, we would like to emphasize the relevance of a multidisciplinary perspective. Thus, when appropriate efforts are put into action, we believe it is possible to help young people to become involved as subjects in the exercise of their sexuality.