INTRODUCTION

Over the past 15 years, a consensus has developed regarding the process and techniques that should be used to interview minors who are victims of abuse and mistreatment. There are guidelines that professionals can follow when interviewing minors who have been victims of sexual abuse(1). The development of these frameworks is related to the importance of the information obtained during interviews in determining whether or not sexual abuse has occurred when there are no physical signs of the event.

In order to conduct an adequate interview and interpret both the minor’s behavior and the content spoken, the professional must have experience working with minors and basic training in interviewing cases of sexual abuse.

IMPORTANT ASPECTS FOR INTERVIEWING MINORS

For professionals who intend to interview minors, it is useful to seek to understand some aspects of child and adolescent development, including reasoning processes, attention, language, and memory(2). Psychological studies show that minors, particularly young children, are influenced by adult suggestions(3). Interviewed many times, they may reconstruct events that did not happen and, after a while, forget important events.

Understanding the effect of trauma on these cognitive processes is also important. For example, children and adolescents protect themselves by distancing themselves from traumatic events, i.e., they dissociate. The cognitive process of dissociation means that minors may have trouble retrieving unpleasant memories that they have tried not to keep or forget, once they have been recorded.

The process

The existing protocols agree on the fact that the professional (or professionals, if more than one is present) responsible for the interview must establish a relationship with the minor, introducing themselves and explaining the interview process, which should give priority to the narrative style rather than questioning. When it is necessary to obtain information from the minor to clarify aspects of his/her account, open-ended questions generate more precise and less contaminated information. The questions can be incorporated into playful activities. The interview should take place in a place where the minor feels safe, if possible adapted to the process. In an ideal situation, the interviewer will look for a suitable place for the interview, which will be quiet, with objects that will help in the conversation, such as toys, dolls, paper and colored pencils for writing and drawing.

Before starting the interview, it is recommended to gather all the information that agencies from different sectors have about the minor in order to place the information obtained in the context of his or her life. During the interview, the number of people present in the room should be limited. It is useful to have two people present because one can ask questions while the other records the content of the conversation and notes observations. Since most cases of sexual abuse are committed by men, at least one of the interviewers must be a woman. In the rare case where it is suspected that the abuser is female, it would be better for the interviewers to be a woman and a man.

The interview process can be aided by the presence of a person with whom the minor identifies. If the minor is able to answer, ask who he or she would like to be present during the interview. If not, the professional should seek information about who the appropriate person would be, since it is not always a family member. It is also important to decide who will be responsible for interviewing the minor and what their availability will be if more than one interview is necessary.

Children and adolescents have difficulty talking to people they do not know, and they gradually get used to talking to the same person. If different adults ask the same questions, they may get different answers, because the child thinks that repeating the question means that he or she did not give the right answer the first time. It is always necessary to record the content in writing, or to record it on audio or video, to eliminate the need for repeated interviews with the child.

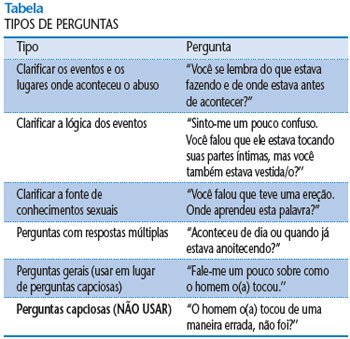

In general, the interview is more effective if the interviewer is sensitive to the child’s level of development. This means that when the professional asks a question, he or she must remember aspects of the cognitive and emotional development of children and adolescents, which will influence the structure of the story and the information that will be included in it. For example, if the memories were recorded when the child was small and did not speak, it is possible that this was done visually. In this case, it is more useful to ask the child or adolescent to visualize what happened before speaking. It is also known that, from a young age, children remember events, people and places, but they are not good at assessing what is true. To help the recall process, it is sometimes advisable to ask more specific questions, such as: “Did the person look like someone else you know?”; “If so, why?”. Other questions that help with the ability to remember the child are described in the

Table .

Being sensitive to a child’s developmental level also means:

- use appropriate interviewing techniques (drawings, stories, games, dolls, etc.);

- use observations (family interactions, the child’s reactions to different stimuli, whether people or places);

- use positive language. For example, say “Do you remember the color of your clothes?”, instead of “Don’t you remember the color of your clothes?”;

- use the same words that the minor uses to describe his private parts.

With young children, specific dolls with genitals can be used, but only after sexual abuse has been confirmed. Otherwise, the professional may be accused of introducing misleading information into the interview or, worse, of abusing the minor and traumatizing him/her by introducing sexual information that is not appropriate for his/her age and stage of development.

The format

An interview with a minor who is or has been a victim of sexual abuse could have the following structure.

- Initial phase of developing a relationship: the professional should begin the interview after having developed a relationship, or rapport , with the minor. The professional (or professionals) introduces themselves by stating their name, their profession, the purpose of the interview and how they will record the content of the interview, i.e. whether they will record or write down the conversation. They may also ask about the minor’s life, to obtain some information about their friends, school, etc. To get to know the minor better, the professional may mention that they understand the difficulty of talking about intimate matters.

At this stage, the professional can bring up important topics that may influence the information obtained, such as telling the truth. Questions such as “Do you know what telling the truth is?” and “If I told you I had green hair, would that be true?” are useful. You can also use a story in which the character lies to give an example of what a lie is to a younger child. Stories are a more concrete way to differentiate between, for example, lying and pretending during a game.

- Free narrative phase: this phase can begin with a request to talk about some past events (a party or a birthday) to estimate the child’s ability to remember. This allows the child to assess the quality and quantity of details that he or she can remember. In a second stage, the topic of the interview will be introduced by asking the child to give a narrative account, using the following phrases: “Tell me what happened to you”; “I want you to tell me about what happened, from the beginning to the end, telling me everything that happened in between”; “Tell me what usually happened when”, if it is a case of repetitive abuse. The interviewer can help the child to remember by asking him or her to “mentally reconstruct the circumstances of the event, and be sure to tell everything you remember”.

There are techniques that the interviewer can use to facilitate the free narrative process, including asking the minor to talk about all the details at the beginning of the interview, even if they do not consider them important. The interviewer should also mention that the minor can vary the order in which they talk about the events and tell the stories from different perspectives (for example, what other people said about what happened). If the minor says that they do not remember something, the interviewer can recommend that they try to reconstruct a mental image of what happened, since the memory may exist in visual form. The professional should not interrupt the minor during the story, because there is always a risk that they will stop talking. More specific questions can be asked later.

- Questioning phase: After allowing the child to talk about the events without interrupting, open-ended questions will be used, which do not require only yes or no answers. These open-ended questions can be of different types, depending on the information the interviewer wants.

- General questions help children remember more details about events and places. Children can be encouraged to talk by asking, “You said that. Do you remember any more details about that?” If the answer to this type of general question is no, the interviewer must assess whether this is due to anxiety or lack of memory. In the first case, the interviewer may suggest that the child make a signal, such as raising his or her hand or stamping his or her foot on the floor, to indicate that he or she knows something but should not talk at that moment. The interviewer may then suggest that the child draw or write about the subject, but never pressuring him or her too much.

- More specific questions are useful for clarifying events, facts, etc., but they should not be confused with leading questions, which put ideas in children’s and adolescents’ heads. Remember that if the interviewer persists too much on a topic, the child is likely to give up answering. If the interviewer uses a sequence of questions without breaks, the child may get confused in his or her answers.

It is essential to minimize the contamination of responses. You should not ask, “What color was the man’s hair?” if the child has not said that the abuser was male. The differences between general questions and leading questions are shown in the Table, as are other types of questions.

- Final stage: The goal of this stage is to conclude the interview on a positive note and leave the child feeling relaxed and unafraid. The professional can praise the child’s efforts, referring again to the difficulties in talking about sensitive subjects such as sexual abuse. The adult, or even the adolescent, who is caring for the child should be given a contact phone number in case they want to speak to someone or have questions about the interview process.

Maximizing a child or adolescent’s ability to remember consists of asking good questions that help them remember the events.

HOW TO EVALUATE THE INTERVIEW

After the interview, the information obtained must be analyzed and evaluated, so that the situation of the child can be understood and whether or not further interviews are necessary. The information from the interview(s) will be used to make important decisions about how to intervene to ensure the child’s safety and well-being. These decisions will often have an impact on the child and the people around them, so it is important to know whether or not the child’s or adolescent’s account adequately describes what happened. Analyzing the following aspects of the interview will help the professional evaluate the quality of the account(4):

- language used by the minor: the use of vocabulary or descriptions not characteristic of a child or adolescent of his or her age, or with his or her level of development – if it was more explicit than normal – indicates the possibility that the minor has been exposed to information and/or sexual acts not appropriate for his or her stage of development;

- pre-interview techniques: interviewers should find out who interviewed the minor to find out whether the interview techniques could have influenced the content of the story;

- lying: adolescents usually have the cognitive skills needed to invent a story of sexual abuse. It is more difficult for a child to construct and maintain a false story of abuse. If the professional suspects that a minor is not telling the truth, he or she should gather information about the situation to find out if the minor has any reason to lie, pretend or disguise, or if he or she is afraid or threatened. Divorce and separation are examples of situations that are related to such behaviors;

- emotions: during the interview it is important to monitor emotions and how they are expressed, for example, in tone of voice, behavior or facial expressions. Professionals who are interviewing must ask themselves whether the emotions presented are those of a child or adolescent who is recounting an experience of sexual abuse, such as anger, anxiety, fear or sadness;

- story logic: the interviewers, preferably two, will pay attention to whether the story has a logical progression or not. That is to say, the child’s story goes from beginning to end. There needs to be a distinction between a logical progression, which gives meaning to the story, and a change of theme in an effort to remember the story completely. In other words, you have to ask yourself: “Does the story make sense or not?”;

- sexual abuse occurs within the context of the child’s daily life: if the story can be understood as being part of the child’s daily life – for example, it happens when he is told to make a phone call at a neighbor’s house, because the family does not have a landline at home – there is an indication that he is talking about events that happened in his life;

- Specific details: If the story has many specific details, such as descriptions of where the act took place, the abuser’s clothing, and explicit details of sexual acts, it is more likely that the minor is not lying. Another important sign that may prove that the minor is telling the truth is the fact that he or she can describe how he or she felt or what he or she thought during the episodes of sexual abuse;

- reproducing some conversations word for word: an important sign that the minor is being truthful is when he or she can reproduce sections of dialogues he or she had with the abuser.

CONCLUSION

This article has focused on the complex process of interviewing minors. In fact, a good assessment not only of the minor, but also of his/her family, is essential for adequate intervention in risk situations. Many times we need evidence of sexual abuse to intervene and stop such behavior. We know that physical evidence is more convincing, but it is not always present. The information that results from the assessment of the minor and his/her family is essential in the absence of evidence, because it influences both the primary protective intervention – focused on protection – and the therapeutic intervention that follows. Therefore, it is necessary that professionals who work with sexually abused minors seek training, support and supervision so that they can interview competently and not retraumatize them.