INTRODUCTION

Assessing the family context of a child or adolescent who has suffered abuse or mistreatment by a family member or stranger can help health professionals make important decisions. The information obtained through a thorough assessment will also help professionals from the Child Protection Agency and the Judicial System, who will finalize the measures to meet the needs of the child or adolescent. They will also indicate who will be responsible for the well-being of the child and his or her family, and which health and mental health professionals will be in charge of treatment and monitoring.

Without an assessment, it will be impossible to answer important questions about the quality of family relationships, attachment between family members, and the parents’ perception of the impact of the abuse on their children and their needs. Furthermore, without an initial assessment, it will be impossible to determine whether or not there have been family changes after the intervention recommended by the authorities and to know whether it is advisable for the child or adolescent to remain with his or her family.

The format of the interviews, the techniques used, and the details obtained during the assessment may vary. This depends on whether the assessment process is part of an investigation or expert assessment to obtain evidence, or whether the most important goal is to assess the family and make decisions about how to ensure the future well-being of the child or adolescent. This article aims to describe high-risk family relationships, as well as detail some aspects and themes that will help the health professional in structuring an interview with families in which:

- there is suspicion that mistreatment is taking place;

- there is concern for the well-being of a child or adolescent.

FAMILY ANALYSIS

Over the past 20 years, the systemic thinking that underpins family therapy has contributed significantly to understanding how abusive and mistreated families function, the cycles of violence, and the dynamics of professional networks responsible for the safety of children and adolescents within these families.

The systemic perspective recognizes the family as a functioning unit greater than the sum of its individual parts, i.e., an organism(1) that has its own life cycle(2). The systemic literature is extensive and describes families in terms of characteristics, dynamics, and functions.

Important concepts for assessing families include patterns of interaction, hierarchies, and subsystems, as well as spaces and boundaries, emotional bonds, and connections between different members and different ages. The family is responsible for both the care and development of its members, internally, and for aspects aimed at adapting to society and continuing its culture.

One of the essential functions of the family is raising children, from birth until they become independent, providing support and protection to each of its members.

A

functional family is one that is perceived as being predominantly affectionate, with good communication, cohesive and with flexible rules, but clearly defined limits and boundaries, providing its members with the resources necessary for individual growth and support in the face of life’s difficulties or intercurrent illnesses. The balance between protection and autonomy offered by the family will develop, in children and adolescents, the basic confidence necessary for organizing their behavior and integrating their self-esteem.

- High-risk families: abused parents and family dynamics

In families known as high-risk, there are often problems with attachment and communication, and there is a lack of sensitivity even to the needs of children of different ages. Parents’ expectations regarding responsibilities and general behavior are not appropriate for children and adolescents. Abusive parents may have suffered from lack of care or mistreatment during their childhood. They did not have adequate role models to help them develop the skills to be parents. Parents who are victims of abuse and who repeat the cycle of violence and abuse may display rigid and inflexible behaviors and thoughts. They often have low self-esteem and a lack of empathy and trust in others. Conflicts over care and control that developed during childhood or adolescence may persist into adulthood if they do not receive help or support from health professionals or loved ones they trust.

In the absence of such support, adults who have been abused may form dependent relationships, becoming deeply affected by the experience of loss. They experience many conflicts in intimate relationships, which are the result of insecure attachments developed during childhood, resulting in unstable relationships in adulthood. If they also had difficult childhoods and idealized them, they probably do not understand the impact of these experiences on their interpersonal relationships, especially with their children. The structures of the families they form may have rigid or diffuse limits and boundaries that make communication between the current subsystem of parents and children difficult.

Incestuous families

have been described as rigid and patriarchal, maintained by a fragile union. The fathers of the family are dominant, that is, they are people who use force over the women. Due to the weak positions of the women and the protective mothers, the daughters find themselves in vulnerable positions. Other descriptions of these families portray blurred boundaries between the subsystems of parents and children. Weak men, dominated by their wives, turn to their daughters in an attempt to find a partner on the same emotional level, especially if the wife refuses to have sexual relations with him. Parents may seek comfort and security that they have not received in their relationships with their children. Children and adolescents who do not meet expectations of providing affection when requested are punished, sometimes severely. The normal needs of children who want constant attention and care can provoke a reaction of anger and frustration because the parent is unable to give what he or she has never received.

Discipline issues are seen as a conflict over control, not as a matter of imposing limits on an immature and dependent being in order to educate him. These distortions in perception can also be the result of a lack of understanding and/or knowledge of children’s development or of concern for their unmet needs, because they did not have a family context that facilitated this learning. The result is the same: the family does not fulfill its basic functions of providing care, security, support and education to children, and thus the various types of mistreatment and neglect appear.

Child abuse and mistreatment occur in all social groups, but circumstances of poverty, inadequate housing, poor health and education are risk factors for some types of abuse – especially cases of physical abuse and neglect. In this context, it is necessary to identify the responsibility of authorities and society to help families living in extreme poverty – a situation seen as

family social abuse – to create a better environment for their children. It will be very difficult for these families to change on their own, without the support of material and economic resources.

Other risk factors include families with drug and alcohol problems or families who are isolated and unsupported by services or other family members. Sometimes families do not use community support or support networks because they lack information or for other reasons, such as mental health problems, which should be identified during the assessment.

Finally, it is important to remember that the concepts and descriptions developed here are intended to help professionals understand the dynamics and processes within a family unit. They should not be used to stigmatize families, but rather to make pertinent observations that can help them.

The best way to promote the well-being of children and adolescents is to first communicate a desire to work with family members to identify the support, therapy, and other services that are needed to improve their health care. Adults who abuse because of their own experience of abuse and other disadvantages can, with the help of appropriate services, develop new patterns of interaction as alternatives to abusive patterns.

An important goal of the assessment is to differentiate the minority of

sociopathic or psychopathic adults who develop superficial and violent exploitative relationships, attacking without feelings of guilt or empathy, and who do not change their behaviors and social conduct. It is up to the professional to determine the capacity for change of the non-sociopathic or psychopathic parent and the conditions necessary for these changes to occur.

IMPORTANT TECHNIQUES AND TOPICS

Before beginning any assessment, the professional should clearly explain the goals of his/her work and verify that the family understands what he/she is proposing, in order to avoid any problems later on. The need to obtain data using a variety of techniques arises from the complex nature of the problems involved in cases of child abuse and maltreatment, which are always susceptible to misdiagnosis. Assessment techniques include observations in different contexts of the patterns of interaction between family members and semi-structured interviews with family members that complement those that took place with the children. Today, there is a more frequent use of standardized instruments, such as the Family Environment Scale (FES)(3) and the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale III (FACES)(4), to assess the characteristics of families.

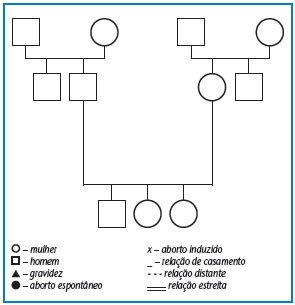

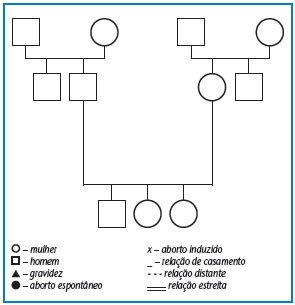

Due to the complexity of family dynamics, it can sometimes be useful to draw the family structure. There are different techniques, but one of the most commonly used is the genogram (Figure).

Figure – Genogram and some symbols(2)

A genogram is a family tree, usually describing the characteristics of each person up to three generations, to:

– place the current problem in a historical context;

– clarify intergenerational patterns, such as violence, neglect or sexual abuse;

– explore myths and beliefs;

– help understand the complexity of the family, the repetition of patterns of behavior and the myths and legends that support these patterns between generations.

Identifying patterns of behavior within high-risk families and the difficulties parents face helps determine where problems exist. Issues related to parents’ behaviors that are recognized as important for assessment (5) include:

– Analysis of parents’ knowledge and attitudes toward the job of being a parent – parents often have unrealistic expectations of their children’s abilities.

– Perceptions and interpretations of their children’s behaviors – often normal behaviors (crying, complaining, or arguing about limits) are interpreted negatively (as if the child or adolescent wanted to hurt the adult).

– Emotions and behaviors in the face of stress – if domestic violence is present, a parent may be neglectful, neglectful of children because they are traumatized, or dissociate themselves, demonstrating symptoms of post-traumatic stress. There is also research on physical violence that indicates that parents who mistreat children become more irritable and feel more discomfort when faced with their children’s emotions.

– Parent-child relationship style – whether there is affection, concern, fear, anger, or whether a parent identifies his or her child with an unloved relative.

– Quality of attachment – interviews and observations are necessary to determine whether an act of violence by an adolescent toward his or her mother is a behavioral disorder that is related to a lack of limits or violent models within the family or to a violent attachment resulting from a difficult long-term relational history between them.

– Quality of parenting – details and observations related to the following topics can help the health professional understand the experience of being a parent to an adult, how their care is related to their own family history and capacity for change(6).

The following questions related to each topic are examples to guide the information that the professional needs to take from previous reports of others, interviews and observations that he or she will make but that should not be directed directly to the family, but rather adapted to the understanding of its members.

- Parents’ relationship with their role

– Do the father and mother provide basic physical care for hygiene, health and nutrition?

– Do the father and mother provide appropriate emotional care for the child or adolescent’s level of development? Is there overprotection or not enough protection?

– What attitude do the father and mother demonstrate when faced with the tasks of caring for a child or adolescent?

– Do the father and mother understand and accept the responsibility of being a parent?

– Who is responsible for the safety of the children? The parents or the children themselves?

– If there are problems related to care and safety, are the father and/or mother aware of them?

- Relationship between parents and child

– What emotions and feelings do parents demonstrate towards the child or adolescent?

– Do parents have empathy for the child or adolescent?

– Are the child and/or adolescent seen as a separate being? Or is there a lack of limits and respect?

– Are the children’s needs seen as more important than the parents’ desires?

– What level of awareness and understanding do parents have of the impact of their family history on caring for their children? Do they idealize their childhood?

– Can parents maintain a good quality relationship with a supportive person?

– Is the child or adolescent too involved in the parents’ dysfunctional relationship? Are they being used in a process of blackmail?

– What is the impact of stress on the parents’ relationship? Does it result or has it resulted in violent behavior and neglect?

– What is the meaning of the child or adolescent to the parents? Is he or she viewed negatively because he or she was unwanted or the child of an unloved parent?

– What are the characteristics of the child or adolescent that make it difficult to care for him or her? Special needs, illness, learning difficulties, etc.?

– What is the child’s attitude toward his or her parents? Aggressive, resistant to imposing limits, passive, seemingly fearful, etc.?

- Interactions with the world

– What social support networks and relationships exist? Family or community? Does the family seem to isolate themselves?

– How do family members behave with health professionals now and in the past? Is there a possibility of collaboration?

– Has there been any previous intervention in the family? What were the parents’ reactions when they received help previously?

– Has there been follow-up? What was the outcome?

– What would be the impact of therapeutic intervention now?

CONCLUSIONS

This article briefly describes some important aspects of an assessment carried out with a high-risk family suspected of child or adolescent abuse. The interactions described can inform observations made during the clinical and therapeutic assessment process. The themes and questions can structure an interview that will help to understand the parents’ knowledge about their children’s needs, the way they treat them, their attitudes and emotions, as well as the vulnerable aspects of the family system.

Using this information with other details about the family’s community and social context and their previous relationship with health services and professionals involved in their care, it is possible to have a preliminary idea of whether or not there will be the possibility of changing the family context to promote the well-being of the children and children and adolescents who seek help from the health system in cases of abuse and maltreatment.

Figure – Genogram and some symbols(2)

Figure – Genogram and some symbols(2)