INTRODUCTION

Today’s world, marked by rapid technological change, globalization of markets, rapid development and dissemination of knowledge and information, has to face the great challenge of ensuring educational opportunities for the entire population. In this sense, distance learning (DL) has been used by many educational institutions, both public and private, as a way of responding to these challenges.

According to Brito(2), due in part to sectoral reforms, in most Latin American countries there is a growing interest in improving the quality of care in health services. Therefore, managers have been seeking to increase educational actions aimed at promoting substantial changes in staff performance on a massive scale and with national scope. Considering that significant technical learning can be the basis for improving and changing health practices, DL courses have also been encouraged in Brazil as a strategy for accessing continuing education in the health sector. Health education is a process that brings work to the core of the teaching-learning process, making it a source of knowledge and favoring collective and multidisciplinary participation.

At the request of the Ministry of Health, Technical Area for Adolescent and Youth Health and Family Health Program, the Center for Studies on Adolescent Health (NESA) of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) developed self-learning modules for professionals in the basic health network who care for adolescents and youth. These modules sought to promote reflection that would enable the transformation of the practices of these professionals in order to provide comprehensive care with a multidisciplinary approach.

The objective of this work is to present the methodology of the

Self-Learning Modules in Adolescent and Youth Health and the results of the evaluation of the first professional training courses.

METHODOLOGY

“Learning, like thinking, results from a process of construction…” (Freire, 1996)

The self-instructional modules are presented based on clinical histories, with different degrees of complexity, which aim to facilitate reflection by the professional, as well as to promote debates with the health team. As a work methodology, it was decided to develop modules with information that would lead to the learning of previously defined skills and abilities. The idea was to expand the knowledge of the professionals so that they could find solutions to health problems that they face when caring for this population group. In view of the need to cover several areas of knowledge, a development team was formed made up of professionals from different areas: speech therapy, history, medicine, nutrition, dentistry, psychology and social work.

The modules created address topics of specific skills, in three thematic axes: growth and development; sexuality/reproductive health; and main clinical problems. They also address transversal skills, fundamental for the comprehensive care of the clientele, such as teamwork, ethical issues and health promotion, among others.

To assist in analyzing the situation, generating hypotheses and solutions, and substantiating the proposed solution, theoretical summaries were created about the relevant aspects of each story. The material also has a glossary with the meaning of words that are difficult to understand and/or unfamiliar with could hinder the understanding of the information. There are also tips or reminders, which are issues emphasized in a short and simple way to be remembered when providing care to adolescents and young people.

One of the strategies used to make interdisciplinarity viable was the creation of a reflection and discussion session, so that clinical situations could be analyzed in detail, preferably as a team, with all professionals involved in the care. Studying and deciding together on the conduct of a case should allow for an assessment with different perspectives and help in the division of tasks.

An important point of this model is that the professional would learn by doing, so that in this way theory and practice would go hand in hand. A new pedagogical model was adopted – the pedagogy of interaction – in which a small group or the individual himself would develop his study method, train his skills, select resources more suited to his reality and thus learn to work as a team.

The purpose of the method is to make the group responsible for seeking new information and analyses for their problems. The group must understand and know the first steps on the path to learning how to learn, creating an active process of approaching knowledge in interaction with the object. Knowledge, in order to have meaning, cannot be separated from life; it must be understood as a process that is established in the relationship between people(7).

PEDAGOGICAL METHODOLOGY

The process of constructing knowledge used derives from a principle studied by Piaget called

constructivism , in which knowledge is an operation that constructs its object. Piaget introduces a dialectical position between the poles of the knowledge process: the subject and the object.

Professional training programs, based on this dialectic, aim to ensure much more than a simple mastery of specific knowledge and skills; they seek to transform the professional in their daily attitudes and practices. The conceptual framework is based on competencies that, in turn, can be classified as

transversal and

specific . Cross-cutting competencies refer to the capabilities that contribute to the development of the work as a whole: the ability to work in a team, interact with people, know how to seek information, communicate and express ideas. Specific competencies refer to the technical capabilities and skills defined according to the needs of the service in the exercise of its daily activities.

Within a specific context of public health, safety and well-being,

competence is the ability to apply knowledge appropriately to achieve a specific result. To be qualified for this practice, the health professional needs

skills to perform essential procedures in the management of problems. Monitoring of practical competence is carried out through the enumeration of certain behaviors, which are indicators of performance.

RESULTS

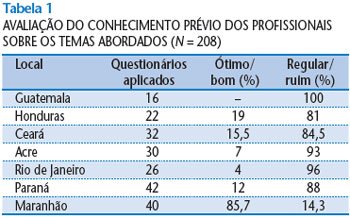

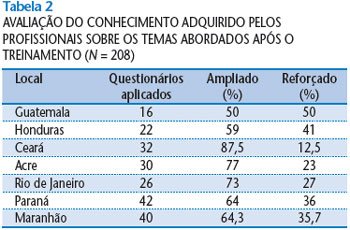

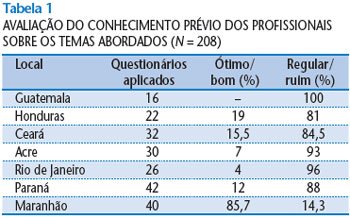

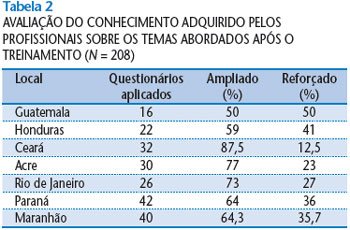

The educational material was used in eight training courses, in different locations throughout the country (Ceará, Acre, Maranhão, Paraná and Rio de Janeiro), as well as in Latin American countries (Guatemala and Honduras), totaling 208 participants. Of the 26 Brazilian states, 12 were represented by professionals from the following categories: medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, nutrition, education, sociology, pedagogy, occupational therapy and veterinary medicine.

The results regarding the pre- and post-training evaluation with the pedagogical material demonstrated that there was a significant improvement in the professionals’ knowledge about the topic addressed (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, there were positive assessments regarding the pedagogical proposal, indicating the possibility of its significant contribution to team training. Regarding the quality of the teaching material, there were positive references indicating clear language, pleasant visual presentation and objective instructions for use.

The additional advantage of not having to travel from their workplaces in search of access to information in more distant training centers was also highlighted.

DISCUSSION

Professional training programs in comprehensive care aim to provide the necessary information for professionals to be able to solve the main problems involving their clientele. In addition, adequate training of professionals and the way in which the content is worked on enable the appropriation of this knowledge by the target population. For this task to be carried out effectively, there must be a qualitative change in the learning processes, so that health teams are trained to interact with adolescents and young people. The new paradigm, which has been developing within cooperative learning, shows access to knowledge that is, at the same time, massive and personalized(10).

Services with better levels of quality, productivity and effectiveness in adolescent care depend mainly on the adequate performance and commitment of each individual. Interdisciplinary teamwork is the only way to have a comprehensive view of the individual, valuing their uniqueness. One of the purposes of professional training as a development strategy in health services is to promote change and the improvement of practical skills.

Therefore, this pedagogical model encourages critical thinking and the construction of new knowledge linked to reality, which takes into account individual and team commitments in decision-making. The purpose of the method focuses on the group’s responsibility to seek new information, analyses and solutions for the problems detected.

This proposal differs from the traditional model of thinking about the training of health professionals, in that the professional himself would be responsible for establishing limits for his practice, referring to other professionals, when possible, and seeking his self-training to climb higher steps in his learning process.

“The process of greater effectiveness in the quality of work, based on continuing education, does not end with the application of strategies. The reason for this is the same as that which generated the difficulties: these are complex social processes that tend to revert and return to previous levels of performance, even when effective changes have been introduced, unless measures are taken to increase the level of effectiveness achieved and unless the changes produced can be monitored and recorded”(16).

The analysis of the assessment instruments indicates that the transversal and specific skills worked on during the course were learned by the participants. The challenge in this work was to construct situations that are close to reality and essential for the safety and effective practice of new knowledge for a new professional. Each professional must seek to be aware of his/her own limits, with a constant effort to improve his/her skills and competencies.

Distance learning is currently a tool that contributes to improving the training of future health professionals and to the qualification for quality performance of personnel already incorporated into the services. The training of professionals who work in the health care of adolescents and young people is essential for the development of health services.

According to Brito(2), when learning by working, professionals seek to give meaning to a situation that often seems incomprehensible. Thus, they find meaning:

a) when they compare or relate this situation to another previously experienced or imagined and rely on previously constructed models and the criteria they used to resolve it;

b) when they understand how the nature of the work and the procedures to which this situation leads fit into the specific professional development project, and decide when to qualify the practice;

c) when they interpret it as a field that opens institutionally or more broadly to an entire work team.

Therefore, when we create a self-learning methodology, we are facilitating learning, both for the professional and for future professionals, and making it truly meaningful. This can bring positive changes in the care provided to adolescents and young people, considering the pleasure they have in learning. The relevance of the course for the professional training of students was also noted, with the perspective of constant adaptation of the content and improvement of the didactic-pedagogical process.

According to L’Abatte(9), there is a need for the human resources training policy to constantly promote and evaluate the processes of continuing education in health. This is only possible through the involvement of the institutions to which the students belong and those that provide the courses, aiming to promote greater integration between the content, the teaching processes, the research and, mainly, the intervention projects.

With regard to the care of adolescents and young people, these initiatives should, ultimately, result in greater adherence to services and the incorporation of healthy habits, which lead to an improvement in the quality of life.