INTRODUCTION

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a term used for a group of disorders characterized by chronic arthritis. JIA is the most common chronic rheumatologic disease in childhood and adolescence, with an incidence of one to 20 per 100,000 people. The diagnosis of this disease is clinical, and is characterized by the onset of arthritis in children under 16 years of age, lasting more than six weeks, with no other identifiable cause of arthritis. The disease should undergo early therapeutic intervention, given its potential to cause deformities and functional impotence; therefore, treatment aims to control pain and inflammation, preserve function and growth. To this end, physical treatments associated with some medications, such as hormonal and non-hormonal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying agents and, more recently, therapy with biological agents such as gamma globulin and anticytokine factors (1-3), can be used.

Cytokines, represented by interleukins (IL), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon, are soluble mediators of immune system cells. Several cytokines are elevated in patients with JIA, including IL-1 and 6 and TNF. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drugs have improved the quality of life of patients, since they relieve pain and swelling of the affected joints. In addition, there is evidence of delayed progression of radiographic lesions(1,4-6).

The objective of this study is to review the use of anti-TNF drugs in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, analyzing their efficacy and main side effects.

JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

Since the late 1970s, this disease has been the focus of study with regard to diagnostic criteria and classification. In the early 1990s, it was decided that the diagnosis would be made based on arthritis that had been present for more than six weeks, ruling out other diagnoses in patients under 16 years of age, and that the subtype classification would be made after six months of disease progression. In 1997, in South Africa, the disease was characterized as juvenile idiopathic arthritis and the classification shown in Table 1 was proposed(1,7).

The most common subtype is oligoarticular (50%-60% of cases), followed by polyarticular (30%-35%), systemic (10%-15%), psoriatic (2%-15%) and enthesitis-related (1%-7%)(1,3,8).

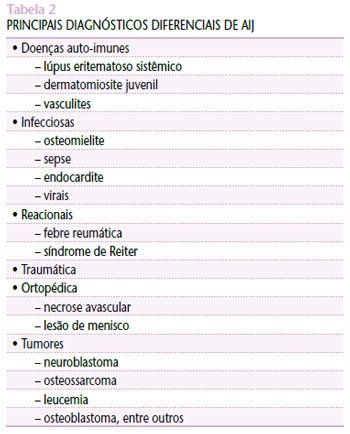

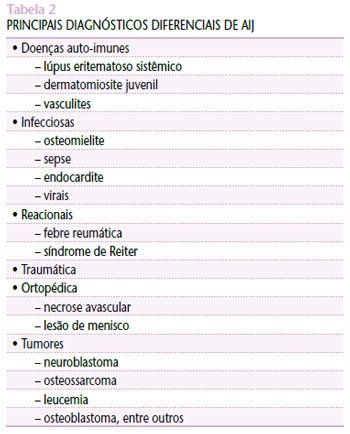

The etiopathogenesis of JIA remains unclear, and knowledge about the real cause of its onset is vague. The main hypotheses include bacterial and viral infections, such as rubella virus and parvovirus B19, trauma, among other possibilities in genetically predisposed individuals(1,7). The differential diagnosis of JIA requires careful investigation, with exclusion of other possible diagnoses. The main diseases to be considered to confirm its diagnosis are shown in Table 2(1,3,7).

Treatment for JIA should begin as early as possible, given its great potential to cause functional impotence and deformities. Multidisciplinary monitoring with physiotherapists, ophthalmologists, orthopedists, psychologists and occupational therapists, among other professionals, is necessary(7). The goals of treatment should be to relieve pain, maintain joint movement and prevent joint deformities and muscle atrophy. To achieve these goals, in addition to medications, physical treatment and occupational therapy should be used(1,7,9).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, cyclosporine and chloroquine are examples of medications that can be used to treat JIA. NSAIDs and corticosteroids are first-line drugs, while the others are called second-line. In recent years, a new class of medications has been added to the list of drugs used in JIA: the so-called biological agents(1,7,9).

NSAIDs are usually the first drugs to be used, and many patients require only these drugs to improve symptoms. They are generally used for four to eight weeks before starting another drug, although there is currently a trend towards starting second-line drugs earlier. Acetylsalicylic acid, naproxen, ibuprofen, indomethacin and diclofenac are examples of anti-inflammatory drugs. These drugs have two major obstacles in the treatment of patients. The first is the fact that, although they reduce morbidity, they are not disease modifiers, that is, they do not prevent erosive arthritis and do not provide a cure. The other problems of this class are their side effects, which include abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, peptic ulcer, headache and epistaxis, among others(1,3,7).

Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs and can be used topically in the joint space, orally or intravenously. However, it is known that this class of drugs can cause significant side effects such as hyperglycemia, cataracts, glaucoma, hypertension, peptic ulcers, growth disorders, etc. Therefore, these drugs should only be used in selected cases, such as severe systemic and polyarticular diseases, chronic iridocyclitis that does not respond to topical medication, and severe systemic complications. Intra-articular corticosteroids can be used as a supportive measure while awaiting the effect of systemic medication(1,7).

Second-line drugs are used when inflammation has not been controlled with the previous drugs. Of these drugs, those that have demonstrated the best effect in JIA are methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and biological agents, such as etanercept and infliximab(1).

Sulfasalazine has proven effective mainly in patients with oligoarticular onset, but it has side effects such as headache, rash, etc. Methotrexate, one of the most prescribed drugs for the treatment of this disease, is mainly used in systemic and polyarticular forms, and patients frequently report nausea as a common side effect(3,7). The association between drug classes can be used to optimize the treatment of patients with severe arthritis, thus increasing the efficacy of the drugs and reducing their toxicity(7).

Biological agents have been increasingly used in the treatment of JIA. Among them, we can mention the IL-1 inhibitor (anakinra), anti-TNF (infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab) and IL-6 inhibitors, which are under study.

ANTI-TUMORAL NECROSIS FACTORS

Etanercept is a soluble and recombinant form of the TNF receptor linked to an Fc fraction of an immunoglobulin. Each molecule of the drug can bind to two TNF molecules, thus allowing their inhibition. In addition to directly inhibiting TNF, this drug can also block biological responses initiated by TNF, reducing serum concentrations of cytokines and expression of adhesion molecules(9-13). Etanercept has been shown to improve the quality of life of patients, in addition to slowing the progression of erosion caused by the disease. When 25 mg of etanercept is administered subcutaneously, its half-life is approximately 102±30 hours, which is why a dosage with this dose is recommended for adults and 0.4 mg/kg for children and adolescents, with a maximum dose of 25 mg twice a week. In a study conducted by Keystone et al., the same beneficial effects were observed when the drug was administered at a dosage of 50 mg in a single weekly dose (or 0.8 mg/kg)(4,6,9). Etanercept is indicated for patients with extended oligoarthritis and those with polyarthritis who are refractory or intolerant to anti-inflammatory treatments and methotrexate. However, in patients with systemic arthritis, its efficacy has not been proven in large studies(1,14,15). Lovell et al., in an open study of 69 patients with polyarthritis, used etanercept in combination with NSAIDs and methotrexate. At the end of the study, they selected the patients who had improved and performed a double-blind study in which some of the patients received etanercept and the other, placebo. In this second study, they observed an improvement of over 70% in 11 (44%) of their patients and over 50% in 18 (72%) when compared to those who used placebo(6,16). Kimura et al., in a study with 82 patients with systemic JIA treated with etanercept for approximately 25 months, obtained a poor response of less than 30%, fair between 30% and 50%, good between 50% and 70% and excellent above 70%(14).

Etanercept is generally well tolerated by patients and, although several side effects have been described, in most cases they are not serious. Infection at the site of administration of the drug is one of the most frequent adverse reactions, followed by upper respiratory tract infections, allergic events and headache, among others(1,3,14). Another adverse effect described with the use of TNF inhibitors is granulomatous infections, which can even be reactivated, with tuberculosis being particularly noteworthy. Other opportunistic infections described are histoplasmosis and listeriosis(6). Lovell et al. reported the presence of varicella-zoster in three cases (one complicated by aseptic meningitis) in patients using etanercept. Therefore, it is recommended that children susceptible to this infection be immunized, whenever possible, three months before starting the drug. Susceptible patients who are exposed to the virus should start taking varicella immunoglobulin and acyclovir as soon as signs of infection appear(1,17).

INFLIXIMAB

Infliximab is an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody composed of a variable fraction of rat antibodies with a constant fraction from human class G immunoglobulin (IgG), i.e., it is chimeric. It is recommended to use it at a dose of 3 to 10 mg/kg, intravenously, in weeks 0, 2 and 6 and, thereafter, at intervals of four and eight weeks(1,13,18,19). Although no large randomized studies have been conducted with infliximab in JIA, it is indicated for use in systemic, polyarticular forms and in juvenile psoriatic arthritis when these are refractory to conventional treatment, having, in these cases, approximately the same effect as etanercept(1,15,20). Side effects were more frequent with the use of infliximab than with etanercept. From an infectious point of view, an increase in the incidence of sinusitis and opportunistic infections, especially tuberculosis, was observed. There is no data proving that viruses such as chickenpox, herpes simplex, and hepatitis B or C, among others, could be reactivated with the use of this drug(1,20). This drug can induce the appearance of anti-double-stranded DNA, which is why some authors recommend its association with methotrexate or another immunosuppressant; however, lupus-like manifestations are rare in these patients. Furthermore, as an immunological manifestation, individuals using infliximab may experience a worsening of multiple sclerosis, and it is therefore contraindicated for patients with this disease(20). People using this drug may manifest symptoms such as headache and hives, but it is rarely necessary to discontinue its administration. Anaphylaxis is a rare effect with the use of this drug(20).

The use of TNF inhibitors in patients with heart failure should be judicious, considering that studies differ on the real negative action of this drug on the heart, causing worsening of cardiac function(20).

CONCLUSION

TNF inhibitors have been of great value in the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, greatly improving the quality of life of patients refractory to traditional treatments, considering that they are capable of controlling the underlying disease, thus improving the daily activities of patients. Despite the side effects, they can already be used with good safety. More randomized studies are needed for better use of anti-TNF in children and adolescents.

Adalimumab is a fully humanized antibody and used subcutaneously every 14 days, but it is not yet routinely used in the pediatric age group.