INTRODUCTION

Every pregnancy entails a certain degree of risk for both the mother and the fetus. However, some factors expose certain groups of pregnant women to increased risk, and these are classified as high risk. According to Caldeyro-Barcia (1973), a high-risk pregnancy is “one in which the life or health of the mother and/or newborn have a greater chance of being affected than that of the average population considered”. When it comes to teenage pregnancy, it is traditionally believed that the risk of obstetric morbidity is greater when compared to pregnancy in adulthood, classifying pregnancy in this age group as high risk. As studies on teenage pregnancy have become more advanced, it has become clear that the increased risk in this age group is due less to age than to socioeconomic level(1).

Teenage pregnancy includes all women under the age of 20. In this group, we found young women who are in their late teens, have a certain level of education, are already married, economically established and have made a conscious choice to become mothers. However, we also found those who are in early teens, who are younger, with different attitudes and physical, social and cultural situations. The fact that we did not divide the group of pregnant adolescents into early and late may represent a bias in this study. However, we cannot deny that young age alone (12 to 19 years) is already a risk factor during pregnancy(1).

In this study, we associated the occurrence of teenage pregnancy with some events to establish social characteristics of pregnant adolescents and show how pregnancy influences these factors, thus establishing the social risk imposed on the adolescent by pregnancy. To this end, we chose some social parameters that can provide us with an insight into the behavior of pregnant adolescents, such as literacy (illiteracy and low level of education), marital status (insecure), smoking (pregnant woman who smokes cigarettes) and nutritional status (<45 and >75 kg), which are considered risk factors in pregnancy by the Ministry of Health (MS)(2). Uncertainty about the date of the last menstrual period, access to prenatal care and the time of the beginning of this care can indicate the socioeconomic level of pregnant women, as they show the level of information and support that these pregnant women are receiving from both their parents and the government(3). The introduction of syphilis as a social fact is due to the importance of the association of this disease with the sexual behavior of pregnant women. As it is a sexually transmitted disease, it can demonstrate the

sociosexual transformations that are occurring with adolescents, who begin their sexual life earlier without, however, being well informed about it(4).

The objective of this study was to evaluate adolescence as a risk factor for some social outcomes during pregnancy.

METHODOLOGY

The population eligible for the study was admitted to a level II maternity hospital, the Maternidade-Escola da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), from January 1, 1996 to October 31, 1999. The study was designed as a retrospective cohort study. The research sources were data taken from the prenatal monitoring card and medical records from the period of hospitalization, recorded by filling out the Perinatal Computer System of the Latin American Center of Perinatology (SIP/CLAP) form. The EpiInfo version 6 program was used for data management and statistical analysis. The study factor was adolescence compared to adulthood. Patients whose ages ranged from 12 to 19 years (adolescents or exposed group) and from 20 to 34 years (adults or unexposed group) were included in the study. A total of 4,956 patients were observed, of which 1,004 (20.3%) were classified as adolescents and 3,952 (79.7%) as adults. The following social outcomes (group characteristics) were considered and classified: literacy (yes/no), marital status (married=marital life/unmarried=living without a partner), doubts about the date of the last menstrual period (yes/no), prenatal care (yes/no), time of initiation of prenatal care (trimester), smoking (yes/no), syphilis (VDRL+/VDRL-), and nutritional status (assessed by body mass index [BMI] divided into three categories: 13-19.5 [nutritional deficit], 19.6-29.5 [normal weight], and >29.6 [overweight]).

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Maternity Hospital of UFRJ.

RESULTS

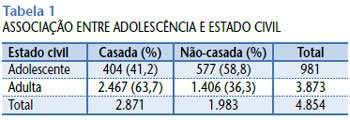

We observed that unmarried marital status (RR=0.65; CI=0.6-0.7; χ

2 =164.21;

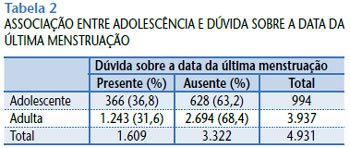

p < 0.001) (Table 1), presence of doubts regarding the date of the last menstrual period (RR=1.17; CI=1.06-1.28; χ

2 =9.95;

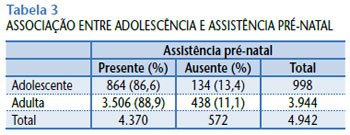

p = 0.001) (Table 2), lower attendance at prenatal care (RR=0.97; CI=0.95-1; χ

2 =4.19;

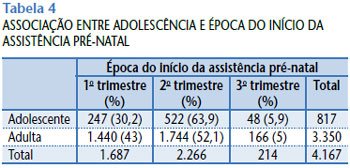

p = 0.04) (Table 3), late start of prenatal care (30% of adolescents versus 43% of adults in the first trimester) (χ

2 =44.38;

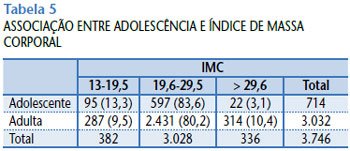

p < 0.001) (Table 4) and a higher proportion of low BMI (13.3% of adolescents versus 9.5% of adults) (χ

2 =43.3;

p < 0.001) (Table 5) are statistically associated with teenage pregnancy.

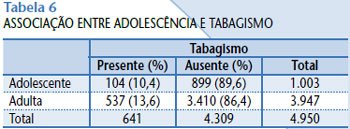

Smoking was lower among adolescents (RR=0.76; CI=0.63-0.93; χ

2 =7.43;

p =0.006) (Table 6).

The associations between teenage pregnancy and illiteracy (RR=1; CI=0.99-1.01; χ

2 =0.05;

p =0.82) and teenage pregnancy and positive serology for syphilis (RR=1.08; CI=0.68-1.7; χ

2 =0.1;

p =0.74) were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Comparing our results with those in the literature, we can observe that there is support for our conclusions, as well as contradictions in relation to them.

In this retrospective study, we observed that pregnant teenage women are more likely to not have a partner than adult women, which is supported by the literature(1,5,6). This may be due to young age, as well as to the pregnancy itself, since the partner may feel pressured and withdraw from the pregnant woman’s life.

Lower frequency of prenatal care, as well as later initiation of prenatal care by pregnant adolescents, seems to be a fact recognized in the literature(1,6,7), and may be due to restricted access to the health system, ignorance regarding the benefits of prenatal care, delay in pregnancy diagnosis(1), the tendency of adolescents to deny their pregnancy and fear of being rejected(8). We also see that adolescents tend not to be able to accurately report the date of their last menstrual period. These facts may be associated not only with their young age, but also with poverty and low level of education(9).

Regarding the nutritional status of pregnant adolescents, we observed that they tend to be shorter and weigh less, because they matured earlier(10), and should have a greater weight gain than adults during pregnancy, to minimize risks to the health of the fetus(11,12).

According to our studies, the presence or absence of illiteracy among pregnant adolescents and adults is not statistically significant. What we see in the world literature is the association of teenage pregnancy with low education level(1,9), not with illiteracy per se, since at the age at which adolescents become pregnant, in most cases, they are already literate.

Other studies show that pregnant adolescents, contrary to what might be expected, tend to use not only cigarettes, but also alcohol and illicit drugs less than adults(13,14). Regarding smoking, this is also our view. We observed that adolescence was a protective factor against smoking during pregnancy. There are, however, studies that observe greater cigarette use among adolescents, compared to adults(7).

Regarding positive serology for syphilis, there was also no statistically significant difference between the groups studied in this study. However, we found reports in the world literature of a greater probability of pregnant adolescents, in relation to adults, to present sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including syphilis(15-17). It is also reported that syphilis is related to the use of illicit drugs and the exchange of sex for money and drugs(18).

CONCLUSION

We observed that adolescence influences several social outcomes of pregnancy. Of the parameters chosen by us for the study, we see that some represent a social risk for pregnant adolescents in relation to adults.

Thus, we found that pregnancy in adolescence is associated with

unmarried marital status , lower frequency of prenatal consultations, later start of prenatal care and, also, greater difficulty in correctly informing the date of the last menstrual period.

Smoking is less related to pregnancy in adolescence than in adulthood.

As for the other parameters studied (illiteracy and syphilis serology), we did not find statistically significant differences, which makes the social risk similar for both adolescent and adult pregnant women.