INTRODUCTION

The adolescent population, with individuals between the ages of 10 and 19, can be considered the healthiest compared to other age groups. However, due to pubertal changes, adolescents experience this period in a remarkable way both in biological and psychosocial aspects. At this time, they begin to feel a series of impulses that lead them to seek new relationships, with the formation of an emotional partner and independence from their family. All of these events lead them to go through experiences that will mark them for the rest of their lives.

Little by little, adolescents begin to face situations arising from the process of independence. Thus, in the school environment, they try to personally resolve their pedagogical problems with teachers and principals; in the sports area, with coaches and sports technicians; in the health system, with doctors and health professionals, among other examples. This is when adolescents need support and respect the most, because when dealing alone with adults who provide services, a relationship begins that can be positive, establishing trust in their surroundings whenever they need support and/or treatment; or negative, which can lead them to avoid seeking help in the event of a need, making it possible to increase and worsen their problems.

Hospital care for adolescents is very often provided in emergency hospitals due to the characteristic of this phase of life in which the subject is more exposed to problems involving accidents and traumas in their daily activities. From these units, they are referred, if necessary, for hospitalization in the hospital network, where, after discharge, few return for outpatient follow-up.

Thus, the study of hospital morbidity among adolescents takes on special significance, as it can provide information to those responsible for formulating and implementing health programs, in order to prioritize preventive actions.

This article aims to present the causes of hospitalization of the adolescent population in the city of Rio de Janeiro, by sex and age group, indicating which could be avoided through effective health promotion actions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hospitalizations of adolescents aged 10 to 19 years in the city of Rio de Janeiro, in hospitals of the Unified Health System (SUS) and associated hospitals, between January 1993 and 1998, were studied based on secondary data made available by the Hospital Information System of the Unified Health System (SIH/SUS)(22). These data are obtained by processing the records contained in the hospital admission authorization forms (AIH). Long-term hospitalizations (psychiatric and those classified as beyond therapeutic possibility) were excluded, and only normal AIHs were used, that is, the records representative of each hospitalization.

The information from the SIH/SUS individualizes the hospitalization through a sequential number and contains, among other things, data on diagnoses (primary and secondary), coded based on the new revision of the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9), in addition to the procedures performed. The records in this database are organized according to the months of the presentation dates and the dates of competence of these forms(2). From 1997 onwards, the diagnoses of hospitalizations began to be classified according to the tenth revision of the ICD (ICD-10). Therefore, for this reason, only some problems were studied until 1998.

To calculate the coefficients or hospitalization rates, the number of hospitalizations by age and sex was used; as the denominator, the population data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE)(3) from the 1991 Demographic Census and the 1996 Population Count, estimating the values year by year, by sex and age group. To calculate the birth rates, the total number of births, including surgical births, was used, divided by the total number of hospitalizations due to complications of pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium (chapter XI, ICD-9), and multiplied by 100. For the cesarean section rates, the total number of surgical births by age group was calculated as the numerator and the total number of hospitalizations due to childbirth was calculated as the denominator, multiplying it by 100. For the abortion rate, the number of post-abortion curettage procedures was adopted, which was divided by the total number of hospitalizations due to childbirth and multiplied by 100. The hospital maternal mortality rates were calculated by dividing the number of deaths resulting from hospitalizations (according to chapter XI, ICD-9) by the total number of hospitalizations due to complications mentioned in the same chapter, multiplying it by 100,000.

Among the causes of hospitalization, due to their large volume and relevance, we selected for study: diseases of the genitourinary system; injuries and poisonings; and pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium.

AIH records are computed at the time of delivery to be reimbursed by the SUS. Therefore, if a delivery occurs at the beginning of the month, it will only be charged at the end of the same month. Monthly records were used to construct the model. Since the data refer to the patient’s post-discharge, this fact may have influenced the interpretation of the results.

This study used a database from the SUS Hospital Information System (SIH). The SGT (Table Generator System)

software was used to retrieve the data and subsequently process it on a microcomputer. The data were prepared for statistical analysis using Microsoft Excel version 5.1, and the STAMP version 5.0 and SPSS software (18, 19) were used to analyze and model the historical series . Microsoft Power Point

software was used to present the graphical results of the study .

RESULTS

According to the IBGE, the Brazilian adolescent population in 1996 was estimated at 25,850,150 individuals, representing 22% of the total population. Individuals in the 10 to 14 age group were those who least used the hospital network for hospitalizations, corresponding to only about 2% of the total; those aged 15 to 19 accounted for 6.8% of the total hospitalizations.

In the same year, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the adolescent population was estimated at 945,284 individuals and suffered 32,960 hospitalizations. Of this total, the 10 to 14 age group accounted for 1.6%, while the 15 to 19 age group accounted for 5.3%. Based on these data, it can be seen that the 15 to 19 age group had 3.5 times more hospitalizations than the younger age group.

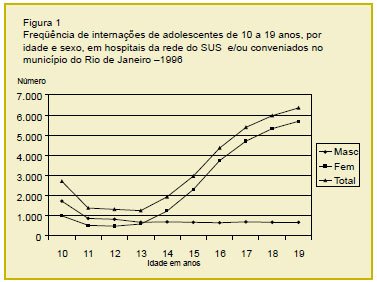

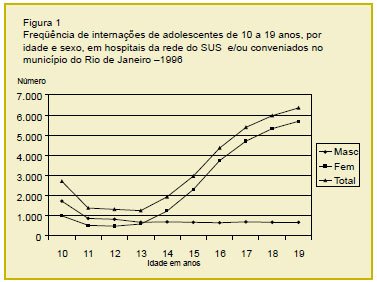

The reasons for hospitalization of adolescents in hospitals in the SUS network and associated hospitals in the city of Rio de Janeiro vary between genders and according to age group. In this descriptive study, overall, it is observed that hospitalizations of female adolescents show a growing increase, mainly from the age of 13. The volume of hospitalizations of adolescents of the opposite sex, at the age of 10, is large, with a progressive decrease until the age of 13 and then stabilizing until the age of 19 (Figure 1). Hospitalizations due to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium represent 63% of the total, with 74% of hospitalizations of adolescents being found in this group.

It is observed that in the age group of 10 to 14 years, male adolescents are predominantly hospitalized in surgical beds, which represent twice the number of female hospitalizations in the same age group. It is worth mentioning that, in this last group, hospitalizations due to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium are in second place in terms of frequency, when compared to other problems that led to hospitalization. However, despite this fact, adolescents with clinical problems were mostly hospitalized in pediatric beds. In the segment of 15 to 19 years, these young women begin to show a predominance in the use of hospital beds, mainly in hospitalizations resulting from causes related to reproductive health, with 89% of hospitalizations for this age group.

Hospitalizations for births in younger age groups (10-13, 14-16 and 17-19 years) showed, proportionally, a progressive increase in the two youngest groups in the last three years studied, while the oldest group, which was in decline in the first three years, began to show an increase in the last. Regarding hospitalizations due to

cesarean sections and

post-abortion curettage procedures , it was observed that younger adolescents had a proportionally higher percentage of hospitalizations than older ones.

Maternal mortality in hospital did not occur in the group aged 10 to 13 years. However, the age group of 14 to 16 years showed the highest percentages in 1993, 42.3%; 1994, 43.1%; and 1995, 41.7%. However, in 1996, the rate dropped to 17.1%, and the 17- to 19-year-old age group surpassed the youngest group, with a rate of 35.6%.

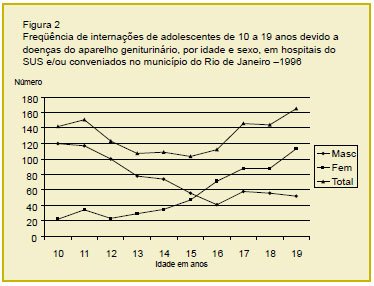

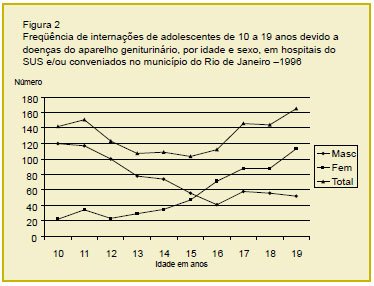

In the age distribution based on more disaggregated age groups, i.e., year by year, it can be seen that hospitalizations of male adolescents due to diseases of the genitourinary system show a downward trend until the age of 17.5, followed by a slight increase. In contrast, adolescents show a progressive upward trend, especially after the age of 12 (Figure 2).

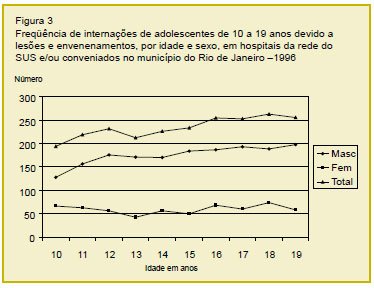

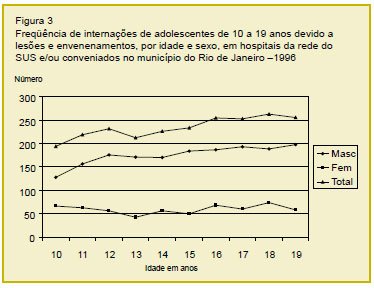

Among hospitalizations due to injuries and poisonings (chapter XVII [codes 47-56] of the ICD-9), fractures predominate for both sexes and age groups, but are more frequent in male adolescents. The same findings were observed in hospitalizations due to injuries and traumas (Figure 3).

During adolescence, individuals go through a period of rapid changes, both biological and psychosocial, which lead to ambivalent behaviors, sometimes childish, sometimes mature(7). Motivated by examples of family behavior, peer pressure, self-affirmation in the community, or even emotional difficulties, unhealthy habits may emerge, especially those related to the consumption of inappropriate foods and experiments with alcoholic beverages, smoking and drugs, among others. It is important to emphasize that these habits can cause health problems, which are avoidable with preventive measures.

This study found that post-abortion curettage procedures showed a progressive increase in younger adolescents, the opposite occurring in older ones. These findings lead to the debate about the insufficient health promotion measures that aim to reach this age group. This study also observed that adolescents, even presenting indicators of early sexual initiation, when they have clinical problems are still treated in pediatric wards.

On the other hand, the high number of cesarean sections indicates late arrival at prenatal care, with complications that could be avoided if these girls actively sought medical care from the beginning of pregnancy.

Dryfoos emphasizes that intervention with adolescents should occur systematically between 12 and 15 years of age, before they begin to be interested in issues related to sexuality(6). Effective intervention in early adolescence could play a relevant preventive role, if we consider the increasing precocity of sexual activity, associated with school failure and dropout.

Borges and Schor, researching a group of adolescents from São Paulo, observed that not only did the adolescents begin their sexual life earlier when compared to those of other generations, but they also had their first sexual intercourse at practically the same age as the men(3). This phenomenon is attributed to the changes that have occurred in the sexual behavior of the Brazilian population, due to the massive entry of women into the job market, the increasing level of education, the widespread use of modern contraceptive methods, as well as the fact that the issue surrounding sexuality is currently on the agenda of the Brazilian public scene.

Stern points out that in Mexico, the poorest sectors show a tendency for adolescent fertility rates to increase, regardless of the age at first pregnancy(20). This consideration shows that in order to also act on this problem, health services will have to go beyond clinical care, seeking partnerships with other sectors to achieve greater effectiveness.

A relevant finding of this study was the number of hospitalizations with diagnoses of genitourinary tract diseases in adolescents, which increased with age, while the opposite occurred among adolescents.

It is known that dysuria is a very common complaint among adolescents. Its diagnosis is often cystitis, urethritis and pyelonephritis, or some other genital tract disease, such as cervicitis and vulvovaginitis(2). Infections are generally not complicated and suggest the onset of sexual activity. Among younger boys, urinary infections are related to anatomical changes in the urinary tract. However, little importance is given to these health problems in the basic network.

Health and/or education professionals do not realize, most of the time, that accurate action/information at the time an adolescent seeks care can provide support for this adolescent to make an appropriate choice to protect his or her health. This is how, with role models and information, adolescents gradually create their own lifestyle. Among the lifestyles adopted, some are considered highly responsible for the causes of morbidity among young people, extending as a chronic disease into adulthood(7).

Muscari believes that, although the problems arising from unhealthy habits constitute a small set, dealing with them remains a major challenge for the organization of care programs for this age group(13). To obtain better results, Rickert et al. propose incorporating the identification of adolescents’ problems and concerns into routine clinical care activities, in addition to health promotion activities(15).

However, Coupey(5), Stringham and Weitzman(21), and Lyra(11) point out that the combination of clinical care and health promotion is the greatest difficulty in organizing services for adolescents. The authors indicate the need to adapt the classic models of the doctor/patient relationship, but do not yet present a solution. Moreno et al. suggest intersectoral integration, especially of education and health, aiming at early and anticipatory action(12).

Cáceres et al. examined the relationship between psychosocial, contextual (drug and alcohol use, sexual coercion and prostitution) and behavioral factors on the one hand and events such as pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) on the other(4). The study proved that cultural factors involved in the non-use of condoms leave young people in vulnerable situations, both in terms of unwanted pregnancy and STDs.

Our study indicated a significant number of hospitalizations due to trauma and accidents, mainly among male adolescents. Sells and Blume Flisher et al. emphasize the great vulnerability of male adolescents and propose better attention to health and environmental conditions(8,17).

Stringham and Weitzman refer to the importance of incorporating questions about involvement in violence into routine consultations with adolescents, as well as outlining counseling and prevention practices(21). It is suggested that health units be integrated with the community and other sectors such as education and culture at the local level, to improve the effectiveness of action on this complex public health problem.

It is also necessary to consider that a program for adolescents must play a relevant role in the health of the population. Major conflicts involving issues that are hidden by society, such as sexuality and drug use, need to have public spaces for discussion and strategic planning, for better resolution. All segments of society should participate, regardless of age, race, religion and/or social class. Global involvement in these issues could help adolescents become aware of the importance of opting for healthy behaviors. Likewise, it is important to find indicators of the effectiveness of actions, through permanent monitoring of missed opportunities in providing comprehensive care to this age group(16).

The discussion of equity in care becomes relevant as recognition of the diversity of this population group indicates that needs are different for different individuals. It also implies the possibility or not of access to the health system. Often, those most in need are those with the least access. When they manage to overcome the difficulties, they arrive late to the services, and in addition, the lack of information leads them to abandon treatment(10).

Care for adolescents raises an ethical issue, since the search for global solutions encourages choices regarding priority of care. We can mention, for example, attention to a health issue in isolation, to the detriment of comprehensive care with effective actions against relevant problems, responsible for the highest mortality rates that affect this age group, such as external causes.

Currently, developed countries have been discussing health promotion as part of their public policies, in the search for healthy lifestyle practices and how to avoid large expenses on problems that could be avoided. Based on these principles, the aim is to democratize knowledge, transmitting information on how to maintain health and avoid disease, preventing unnecessary injuries and, consequently, improving quality of life.