INTRODUCTION

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that occurs after pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (

Streptococcus pyogenes ) in genetically predisposed individuals, mainly those aged between 5 and 15 years. The manifestations of the disease are varied and mainly affect the joints, heart and central nervous system (CNS). It is the most common rheumatic disease among children and adolescents in Brazil, and its morbidity and mortality are mainly associated with the presence of cardiac involvement, which can cause serious injuries and have physical, emotional and social repercussions on the affected individual. Our objective in this article is to review RF, emphasizing its neurological involvement.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenetic mechanism involved in the origin of the disease appears to be linked to a cross-reaction of antibodies originally produced against streptococcal products and structures, which recognize the tissue of the affected individual (such as the heart, articular cartilage and CNS), thus triggering the entire inflammatory process. This cross-reaction, in which host cells are targets for antibodies produced primarily against products of an infectious agent, is also known as molecular mimicry(22).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

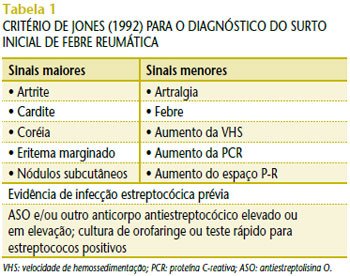

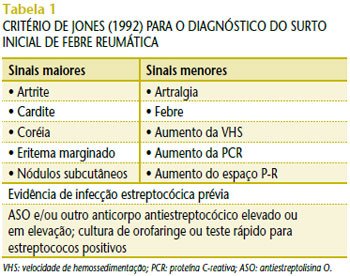

For the diagnosis of RF, we use the Jones criteria; however, these criteria, initially established in 1944, have undergone several revisions and updates. Today, we use the latest revision from 1992(5). The presence of two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria, when there is evidence of previous streptococcal infection, shows high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of this disease (Table 1).

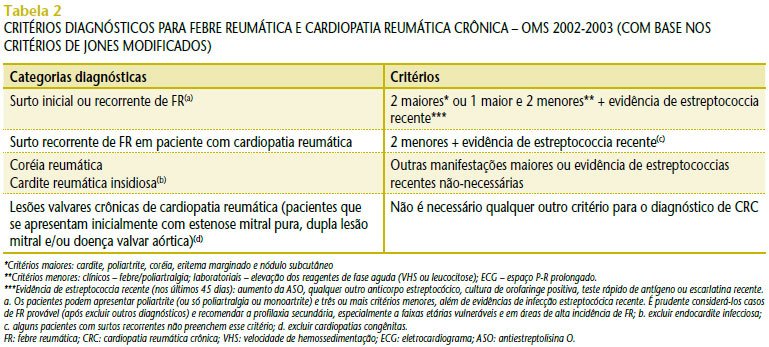

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed, based on the Jones criteria modified in 1992, that the diagnosis of RF be made by diagnostic categories, that is, based on its different forms of presentation (Table 2)(29).

TREATMENT AND PROPHYLAXIS

The treatment of RF consists of two stages: symptomatic and prophylactic. We will comment later on the treatment of chorea.

Symptomatic treatment basically consists of the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for joint manifestations and corticosteroid therapy when there is cardiac involvement. Primary prophylaxis, that is, the treatment of streptococcal infections in the oropharynx with the objective of preventing the onset of RF, is based on the application of a single dose of benzathine penicillin and/or oral antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin, cephalosporin, oral penicillin, ampicillin and macrolides) for ten days, with the exception of azithromycin, which can be used for five days.

For secondary prophylaxis, more than half a century ago, in 1952, Stollerman and Rusoff showed that monthly benzathine penicillin was effective in preventing RF relapses(21). Twelve years later, Wood et al. showed that sulfadiazine and penicillin were also effective(28). However, the superiority of benzathine penicillin in preventing recurrences led the American Heart Association (AHA) and the WHO to recommend its use in prophylaxis at three-week intervals in high-risk countries(1,26-27). Studies conducted in underdeveloped or developing countries confirm the need for prophylaxis to be performed every 21 days(7,11-12,14,16).

The classic secondary prophylaxis regimen adopted in Brazil recommends benzathine penicillin every three weeks, at a dose of 600,000 U, for patients weighing up to 25 kg and 1,200,000 U for those weighing more than 25 kg. If the patient prefers oral penicillin, he or she will receive two daily doses without fail, which is very difficult to achieve for years in a row. In cases of proven allergy to penicillin, sulfadiazine is an option, at a daily dose of 500 mg for patients weighing up to 25 kg and 1,000 mg for those weighing more than 25 kg. The prophylaxis time is prolonged.

Patients without carditis should receive prophylaxis until the age of 18, provided that they have already received it for a minimum period of five years. Those who have contracted carditis should receive prophylaxis until the end of their lives, or at least until the age of 35 or 45. There is a Chilean proposal to administer prophylaxis until the age of 25 in patients who have had carditis but have no sequelae, or in those who have only mild mitral insufficiency as a sequelae, provided that ten years of prophylaxis have already passed(3).

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM INJURY

The spectrum of diseases that affect the CNS associated with possible streptococcal etiology has been increasing. In addition to Sydenham’s chorea (SC), tics, dystonias, parkinsonism, emotional disorders and sleep disorders have also been associated with changes in the basal ganglia due to a probable immune mechanism related to previous streptococcal infection(4).

CS, described by Thomas Sydenham in 1686, is also known as chorea minor, St. Vitus

‘s dance and rheumatic encephalitis and is considered one of the major manifestations of RF. Epidemiological studies conducted in the USA have revealed the occurrence of CS in approximately 10% of patients with rheumatic fever(2). Epidemiological data from studies conducted in Brazil report that CS occurs in 20% to 30% of patients with RF, and recurrence may be observed in approximately 20% to 30% of cases with chorea(9,24).

The diagnosis of CS is clinical and its clinical manifestations may appear within a period of up to six months after the acute RF episode. The signs and symptoms develop insidiously, usually over a period of one to four weeks, and are behavioral, such as hyperactivity, inattention, emotional lability and even obsessive-compulsive behavior. The affected patient presents with rapid, uncoordinated, arrhythmic and involuntary movements(13). Less frequently, other neurological manifestations may be found, such as weakness, headache, convulsions and sensory abnormalities(8). The sensory phenomena – rarely described – are premonitory experiences reported as appearing before the tics. Until now, these phenomena have not been frequently described in cases of CS. However, we intend to clarify whether there are sensory phenomena associated with choreic movements in children with CS, since they may have difficulty describing them due to the subjective nature of the premonitory sensations(17).

Neuropsychiatric symptoms vary in severity, duration, and character. Some of them are also found in Tourette syndrome (TS) and obsessive-compulsive disorders that begin in childhood. Genetic vulnerability is present in all three conditions, with the main differential diagnoses of TS being tics, juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE), neurological diseases, and CNS tumors.

TS is a chronic neuropsychiatric disease characterized by motor and oral tics. Its diagnosis is basically clinical, its prevalence appears to be 1:10 per 1,000 children and adolescents, and the prognosis is good, since most symptoms regress by the end of adolescence or early adulthood. Although many consider it a hereditary disease, environmental factors appear to be important in triggering its manifestation, with streptococcal infection being one of them(18).

Children with

pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) present with acute onset tics or obsessive-compulsive disorders associated with previous streptococcal infection(20). Studies discuss whether PANDAS should be included as a subdivision or a spectrum of CS. Thus, the diagnostic possibilities of CS would be expanded to include neuropsychiatric manifestations currently classified as obsessive-compulsive disorders or Tourette syndrome(15).

Children with CS and PANDAS present a series of similar neuropsychiatric symptoms, therefore distinguishing one disease from the other, especially at the beginning of the onset of symptoms, is not always easy. However, it is important to distinguish between the two diseases, since the therapeutic response of each one to the medications used differs(25).

The proposed pathophysiology for CS and PANDAS is that antibodies against group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus cross-react with the basal ganglia, resulting in abnormal behaviors, involuntary movements, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and/or tics(6).

Interestingly, approximately two-thirds of children with CS also have cardiac involvement. However, a study conducted in the United States between 1993 and 2002 selected 60 children who met the criteria for PANDAS, according to protocols of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). These children underwent two-dimensional echocardiographic examinations with

Doppler , aiming to look for cardiac valvular diseases.

From the results obtained, no significant evidence of lesion was found on echocardiography, except in one patient in whom evidence of mild mitral valve regurgitation was found. All patients had a normal-sized left atrium and a normal-sized and functional left ventricle. Follow-up echocardiograms in 20 of these children showed no significant valvular regurgitation. Thus, the lack of evidence of rheumatic carditis in these children supports the hypothesis that PANDAS may be a neuropsychiatric diagnosis outside the spectrum of Sydenham’s chorea(19).

There is no consensus regarding the treatment of CS. The two most commonly used drugs are haloperidol and valproic acid, both of which have potential side effects. Haloperidol is indicated at a dose of 1 mg/day, with progressive increases of 0.5-1 mg every three days, until remission of symptoms is achieved, without exceeding the maximum dose of 4 to 6 mg/day. Valproic acid is used at a dose of 20 to 30 mg/kg/day. Its action is slower in the first few days, but it is equally effective. The dose should be reduced after three weeks of absence of symptoms. Carbamazepine has been successfully used to treat various cases of movement disorders and was recently described as effective for the treatment of chorea(10).

A study showed that five children diagnosed with CS were treated with corticosteroids in a short period of time. Improvement in involuntary movements was observed within a period of 24 to 48 hours, with complete resolution of the condition between seven and 12 days after starting treatment with corticosteroids, with no recurrence. Although treatment with corticosteroids in patients with CS should be considered, further studies on this subject are necessary(26). It should be remembered that patients with rheumatic fever who developed CS and receive secondary prophylaxis with benzathine penicillin irregularly are subject to a high risk of CS recurrence(23).

The efficacy of secondary prophylaxis in patients with PANDAS in order to reduce tics and obsessive-compulsive disorders has not been established. These patients appear to benefit from treatment with intravenous gamma globulin or plasmapheresis(25).

CONCLUSION

According to different studies, the association of CS with PANDAS is still controversial. Because they present a series of common neuropsychiatric symptoms, some consider them to be the same disease. However, even though they present similar pathophysiology and clinical presentation, when the same medications are used for patients with CS and those with PANDAS, the therapeutic response is different.

The frequency of cardiac involvement associated with patients with CS differs from that of patients with PANDAS. These facts lead some authors to consider CS and PANDAS as different diseases. Further studies on this subject are needed, both because it is rarely addressed and to provide a better quality of life for patients with CS and PANDAS.

In our country, the number of patients with RF is still high. The population’s access to medical care is precarious and this fact, added to the difficult socioeconomic reality in which these people live, contributes to RF becoming a public health problem. Thus, it is clear that preventive medicine, carried out more effectively and focused on prompt care for upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) in children and adolescents, would lead to a decrease in the prevalence of RF, as well as to diminish the impact that the disease causes in emotional, physical and financial terms.