Adolescence is a physiological stage of human development. It is when, in a short period of time and in a rapid and disorderly manner, major physical, psychological and emotional changes occur, generating anxiety and insecurity. Puberty is the biological component of this phase, characterized by the increasing hormonal action that becomes visible with the emergence of sexual characteristics and culminates in the acquisition of reproductive capacity, an important and sudden change, with great repercussions on the behavior of adolescents and repercussions in adult life(1).

Because reproductive health plays an important role in human life, especially in females, the dissociation between the maturation of reproductive capacity and psychosocial maturation is responsible for creating risk situations for adolescents. Menstruation assumes vital importance in adolescence because it represents a significant event in the lives of adult women. The first menstruation (menarche), the beginning of reproductive capacity, the demonstration of the ability to be a mother, as well as the proof that, as females, they can perform their main function (motherhood), are surrounded by numerous taboos that reflect the concern with this moment. Subsequent menstruations bring with them the proof that they are not pregnant, that they can assume their sexuality, feel pleasure, passion, love, etc.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is probably the most common endocrinopathy among women of childbearing age and, because it interferes with reproductive health, it presents several psychological and social aspects, such as changes in body image and self-esteem. Its diagnosis in early stages, especially in adolescence, is quite difficult due to the heterogeneous characteristics of clinical and laboratory factors(4,9). In recent decades, numerous studies have shown that insulin resistance (IR) represents an important factor in the pathophysiology of PCOS(4,8,9).

Results of studies with adult women cannot be fully transferred to adolescence. Adult and adolescent women have different behaviors and interests regarding PCOS. Adult women will be more focused on infertility treatment and the presence of comorbidities, while adolescents will be mobilized and involved with their body image (weight gain, hirsutism and acne) and their sexuality (menstruation, pregnancy and contraception)(3).

PCOS DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA ACCORDING TO THE ROTTERDAM CONSENSUS

The criterion for diagnosing PCOS, according to the Rotterdam Consensus, is the existence of at least two of the following factors, after excluding other causes of hyperandrogenism and menstrual irregularity(10):

- oligo or anovulation (whose clinical manifestations are oligo or amenorrhea, dysfunctional vaginal bleeding and infertility);

- elevated levels of circulating androgens (hyperandrogenemia) and/or clinical manifestations of androgen excess (hyperandrogenism characterized by hirsutism, acne and alopecia);

- ovaries with polycystic morphology (presence of 12 or more follicles measuring between 2 and 9 mm in diameter and/or ovarian volume > 10 cm3 ) on ultrasound.

CLINICAL PICTURE

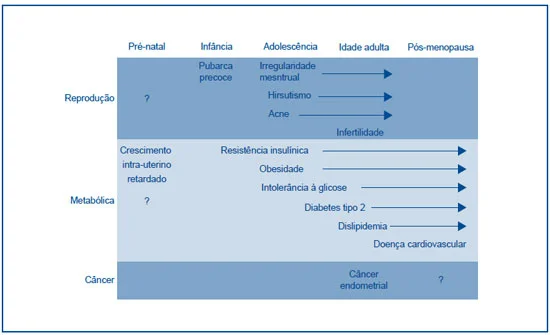

The clinical manifestations of PCOS vary and present diverse phenotypes, reflecting the variable levels of metabolic dysfunction (Figure 1). A history of low birth weight and precocious pubarche confer an increased risk for the onset of PCOS(5), whose symptoms usually begin in the perimenarcheal period(6). It can also begin after puberty, resulting from environmental modifiers such as weight gain and a sedentary lifestyle(2).

Figure 1 – Evolution of PCOS during the stages of life

Source: Sam S, Dunaif A. Polycystic ovary syndrome: syndrome XX? Review. Trends in Endocrinol Metabol. 2003; 14(8): 365-70.

Chronic anovulation presents as menstrual irregularities of the amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea type and, less frequently, with dysfunctional uterine bleeding and infertility. The presence of signs of hyperandrogenism depends on the degree of sensitivity of the pilosebaceous unit to androgens, as well as the time of exposure to them(7), and may manifest as hirsutism, acne, seborrhea and/or alopecia, in varying degrees of intensity and slow progression. Ethnic and genetic influences and local factors produced by the dermal papilla itself may be responsible for the variable intensity of these manifestations. Acne and hirsutism generally manifest in the perimenarcheal period, although hirsutism may appear later, since it depends on the time of previous exposure to androgens. Obesity, when present, has an android or central pattern, and is correlated with insulin resistance (IR) and hyperandrogenism. Acanthosis

nigricans is a marker of IR and type 2 diabetes

mellitus (T2DM). Approximately 50% of obese women with PCOS have acanthosis and tend to have higher IR when compared to PCOS patients without acanthosis.

LABORATORY TESTS

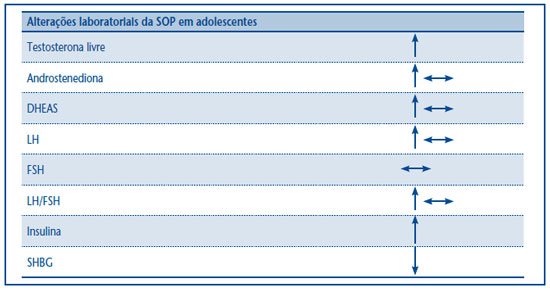

Biochemical alterations in PCOS, as well as its symptoms, are not uniform and their variation is related to the different phenotypes that the syndrome presents. However, most studies comparing patients with PCOS and control groups demonstrate that the most common alterations are increased concentrations of total testosterone, free testosterone, androstenedione, luteinizing hormone (LH), LH/FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) ratio, free estradiol, estrone, insulin and reduced sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG)(4) (Figure 2). The results are more informative when comparing obese and non-obese patients with PCOS. In obese women, we found high concentrations of insulin, free testosterone, estrone and low concentrations of SHBG, LH, insulin-like growth factor binding protein type 1 (IGFBP-1) and growth hormone (GH), compared to non-obese women(4).

Figure 2 – Laboratory tests in PCOS (11)

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; DHEAS: dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; LH: luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; SHBG:

sex hormone-binding globulin.

The clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS in adolescence have not yet been defined and are considered similar to those for adulthood, but it is not always possible to characterize them adequately in adolescence, especially if we correlate them with younger gynecological ages and if we take into account the evolutionary nature of the disease and the characteristics of this age group.

The hormonal changes that occur in the prepubertal period and perimenarche, such as increased gonadotropins, androgens, estrogens and insulin, are well documented. The dosages of gonadotropins and androgens are different in girls with regular and irregular cycles. Therefore, attention should be paid to the menstrual cycle pattern when studying these hormones. Puberty is a state of relative insensitivity to insulin with compensatory hyperinsulinemia(12), therefore the physiological changes of age make diagnosis difficult.

PCOS presents symptoms such as menstrual irregularity, acne and hirsutism in adolescence, isolated or in combination. Early signs can be confused with normal changes in pubertal development, thus missing the opportunity for diagnosis. Identifying hyperandrogenia in the various Tanner stages of pubertal development is not easy, since the cutoff point for androgen levels is not yet well defined, as are the ultrasound criteria for polycystic ovaries in adolescence. It is important to emphasize that ultrasound should preferably be performed transvaginally, which is not always possible, since many patients have not yet initiated their sexual life.

Menstrual irregularity in adolescence is classically considered a physiological change resulting from the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, and is explained by the absence of positive

feedback from estradiol on LH secretion, resulting in anovulatory cycles. Since this

feedback only develops years after menarche, it is a complicating factor, since the main approach in cases of irregularity in this age group is observation during the first two years. Therefore, the opportunity to diagnose the syndrome and its associated pathologies early is lost.

Studies conducted by Van Hoff et al.(12) demonstrate that the presence of oligomenorrhea in the first years after menarche correlates with the persistence of irregularity, and that regular cycles also do not change with gynecological age. In other words, those with regular cycles at the end of adolescence had this same pattern since menarche. Some authors consider that menstrual irregularity since menarche may represent an early or predictive sign of PCOS(13-15).

Approximately 66% of adolescents with PCOS will present symptoms of anovulation. Studies show a history of weight gain preceding the symptoms of hyperandrogenism and anovulation. Currently, the increase in dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DEHSS) occurs as the body mass index (BMI) increases, suggesting that it is an occasional marker of precocious puberty and subsequent manifestations of PCOS in girls. Several studies demonstrate metabolic alterations in adolescents with PCOS, such as hyperinsulinemia, IR, diabetes, changes in body composition, low levels of adiponectin and inflammatory alterations. Insulin levels are twice as high in obese adolescents with signs of hyperandrogenism, when compared to the control group(11).

Unlike what happens in childhood, there is no culture in our country of taking adolescents to the doctor as a preventive measure. However, sexuality, contraception and body image are topics that mobilize adolescents and are the main people responsible for medical consultations among them. We believe that greater knowledge of possible changes in reproductive and bodily functions at this stage, which allow for the identification of PCOS, will help to conduct earlier and more effective screenings. Therefore, adolescence is the ideal age group for implementing preventive actions that will be reflected in adult life.

TREATMENT

In the treatment of PCOS, we must take into account its evolutionary nature, its various phenotypes and the intrinsic characteristics of adolescence. In adolescence, the main concerns are related to body changes, menstrual irregularities and contraception. In adulthood, infertility becomes the focus of concern.

The first and most effective point in the treatment of PCOS will be lifestyle modification. Physical activity should be incorporated into the routine of adolescents. Weight loss in obese patients can restore ovulation and menstrual regularity, as well as reduce IR, acanthosis

nigricans , total testosterone and increase SHBG. Dietary reeducation should be associated with physical activity. This is, therefore, an ongoing task that requires multidisciplinary assistance(8).

Medication options include oral contraceptives (OCs), progestogens, antiandrogens, estrogen inhibitors, and insulin-sensitizing agents. When choosing treatment, we must consider the clinical and laboratory conditions, as well as the patient’s needs.

In current treatment regimens, metformin has been used in patients with signs, symptoms and/or laboratory abnormalities of IR. As an insulin sensitizing agent, it improves insulin sensitivity, signs of hyperandrogenism and menstrual irregularity. Studies with obese and non-obese patients with PCOS have shown the efficacy of the treatment and its ability to restore ovulation, with its effect being more effective in adolescents than in adult women.

OCs with antiandrogenic progestogens are used in combination with metformin in patients with marked hyperandrogenism and/or sexual activity. In patients without IR, we use OCs without combinations. We must take into account the studies that demonstrate the adverse effects of the use of OCs in IR, glucose tolerance and coagulation.

Adolescents with PCOS have a chronic disease, thus requiring constant assistance, with clarifications about the disease, its evolutionary character and possible complications. A relationship with the medical team should also be established to allow adherence to treatment.

CONCLUSION

PCOS is associated with serious health problems, including type 2 diabetes

mellitus (DM2), heart disease, high blood pressure, endometrial and ovarian cancer, infertility, and subfertility. Early diagnosis in adolescence may not only change the natural history of the disease, but also prevent harmful effects at this stage, especially those related to body image.