INTRODUCTION

On July 13th, the 17th anniversary of the Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA) was celebrated, an important milestone in the policy of care and social development of young people, ensuring their rights as citizens. This document determines a care policy that “respects the rights of children and adolescents, adhering to the principles of the 1989 International Convention on the Rights of the Child, which is based on the development of effective instruments in the defense and promotion of human rights” (1).

The ECA aims to protect adolescents, individuals in development; respect their dignity; seek to reintegrate them into society when they are juvenile offenders; and prevent their recidivism (2).

According to Minayo (1996), violence today constitutes a major concern in relation to the health of the Brazilian population, especially for the health sector. Vulnerability to violence is not exclusive to adults, but to all citizens, and is intensified in adolescents, “victims of different types of direct violence: in traffic, fights and conflicts in communities, assaults and family abuse” (4).

Adolescence, with organic and psychological disturbances and transformations, suffers the blows of social violence that manifests itself at all levels (repression and regulation of sexuality, educational and professional pressures, integration problems), marginalization, personality structuring, political and economic exploitation.

The picture of a violent adolescence is well known, whether it is focused on itself (suicides, drugs, mental and social problems, attitudes of failure) or directed towards the community (delinquency, aggression, etc.). Within this same focus, Trassi (5) states that violence constitutes everyone’s daily life, in its various and complex determinations and expressions, with criminality being its most blatant face. “The adolescent’s criminal practice reveals him – the individual – and reveals the collective” (5).

Against the backdrop of violence, there are teenage girls with life stories (and death stories) who have survived violence in its most diverse forms, reproducing it almost as a fate, within an institution that seeks, through its professionals, to rescue what is human within them, with resocialization as the greatest challenge. “Crime is not only a problem for the criminal, but also for the judge, the lawyer, the psychiatrist and the psychologist” (

Apud Dourado.

Op. cit. p. 59).

It is in this context that the study of the epidemiological profile becomes necessary, not only to diagnose and treat diseases and illnesses, but also to outline intervention strategies at the health and social program level that aim to change the approach to adolescents in conflict with the law.

METHODS AND RESULTS

During the years 2004 and 2005, 177 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years old were interviewed, who were serving socio-educational measures at the Educandário Santos Dumont, an institution for adolescents in conflict with the law linked to the Department of General Socio-Educational Actions (DEGASE), in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

After giving their free and informed consent, the adolescents underwent a medical history and a colpocytological examination. The exclusion factor was virginity.

All slides were read in the laboratory of the Integrated Cytology Technology Service of the National Cancer Institute (SITEC/INCA) and the results were presented to the patients, who were treated and/or followed up in the Cervical Pathology Service of the Jacarepaguá General Hospital.

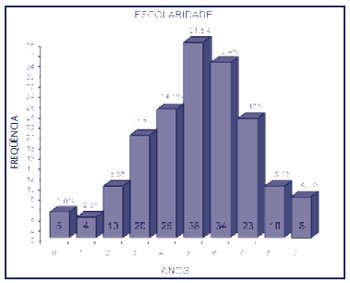

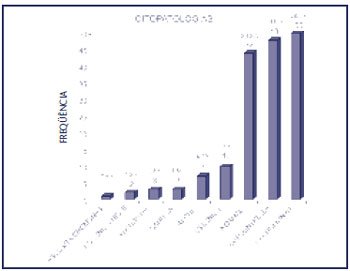

The data in

Figure 1 demonstrate that the majority of the adolescents interviewed had only five years of schooling, although they do not demonstrate the relationship between age and school year. Most of the interviewees were frequently behind in school and had repeated a grade.

Figure 1 – Education

Although 97.2% claimed to have attended school, the majority could only write their name and read with difficulty, and 2.8% were illiterate.

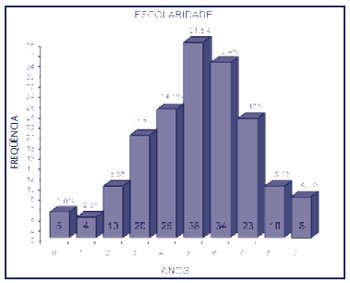

The data in

Figure 2 can be compared to those in

Figures 3 and

4 .

Figure 2 – Presence of drugs in the family (father and/or mother)

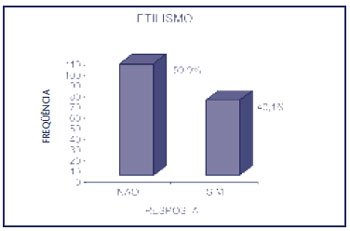

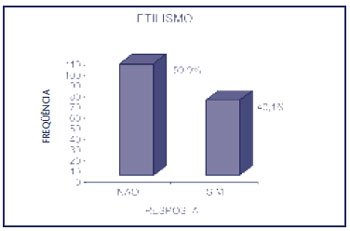

Figure 3 – Alcoholism

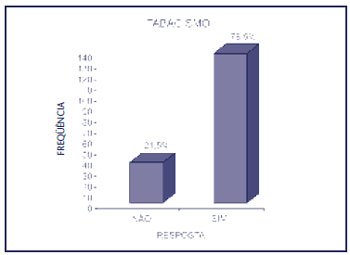

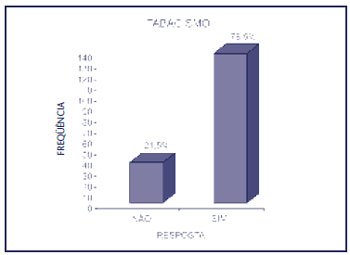

Figure 4 – Smoking

The drugs used in the family were mostly alcohol (37.3%), cocaine (4.5%) and marijuana (1.1%), or all three drugs concomitantly (5.6%). Regarding drug use, 24.4% were marijuana users, 2.3% cocaine users and 41.4% inhalant drugs (loló, cola) and

crack users .

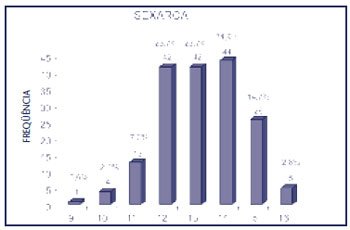

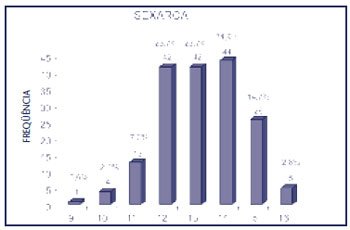

Regarding the age of first sexual intercourse (

Figure 5 ), the average was 12.3 years. The number of partners varied between one (17 girls) and 50 (one girl), with an average of 5.9%.

Figure 5 – Sexarch

The use of contraceptive methods varied between none (40 girls – 22.6%) and irregular condom use (78 – 44.1%).

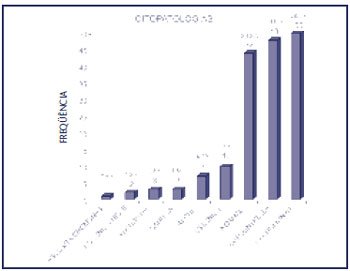

The results of the colpocytology are shown in

Figure 6 .

Figure 6 – Colpocytology result

A patient with high-grade intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) was referred to the Jacarepaguá General Hospital, where colposcopy with biopsy using high-frequency surgery (CAL) was performed, which resulted in carcinoma

in situ . The other patient provided a false address, and it was not possible to contact her after the system was disconnected. All patients eligible for treatment were treated according to the protocol for sexually transmitted diseases (STD) of the Ministry of Health.

CONCLUSION

According to Minayo(3), violence is a historical human phenomenon that affects various social groups. It exists to “dramatize causes, bring them to the public’s attention and, inconveniently, propose and demand changes”.

The study of adolescent offenders, who are poor, unrecognized, rejected, “prisoners of the masses disdained by social exclusion”, allows us to outline not only a profile or diagnosis of this clientele, but also to study health policy strategies to prevent recidivism in the penal system and reintegrate adolescents into society.

Prates(2) reaffirms that “juvenile crime can originate from several factors, such as families with fragile bonds, educational exclusion and government neglect”.

The analysis of the level of education reveals social inequality, which increases the chance of perpetuating inequality and poverty, making social mobility difficult. For Heilborn(6), one of the dilemmas of education in the country is formed by the high rate of repetition and the difficulties of progression or permanence in the school career, which are greatly accentuated in adolescence.

School continues to be a guarantee of non-social exclusion, but, according to Monteiro(7), the problems of public education, articulated with symbolic traits related to gender, contribute to school dropout. Dropping out of school “removes from their lives the only institutional support that mediates their relations with the broader society”(8).

When asked about the reason for dropping out of school, the adolescents gave answers such as: “I got pregnant and didn’t go anymore”; “it was the drugs’ fault”; “I had to take care of my younger siblings”; “I ran away from home to live on the streets”; “I had to earn money selling candy”; “school is very boring, I preferred to be with my friends, messing around”; “there are a lot of fights there, I was always getting beaten up”; “I was ashamed of being pregnant in front of the students and teachers”.

Pregnancy is one of the main causes of school dropout. According to Cunha(9), in his research with adolescents, 64% of them dropped out of school because of pregnancy. Bastos (1998) reports that pregnant adolescents in care centers say they do not want to stay in school “because they are under pressure from principals and teachers”.

The family is the place where affectionate relationships are established, but it is also one of the links in the web of violence that permeates the lives of adolescents. Domestic and school violence have been responsible for adolescents fleeing to the streets, which leaves them subject to other types of violence, drug trafficking and use, prostitution and delinquency. “The streets and/or the early formation of their own families appear as an escape from this situation” (10).

The presence of drugs, both in the family and in daily use, appears as one of the major problems in the lives of these adolescents. It is not surprising that article 12 (drug trafficking) is the main cause of crime among these girls. Drug trafficking becomes an alluring force in a context of precarious institutions – family and school – with a lack of personal prospects, significant adults and self-esteem. Entering into crime is almost a consequence of all these factors.

Studies conducted on families indicate that violent parents and those who suffered aggression in childhood have alcohol as a common factor, and that the use of illicit drugs represents a direct cause of child abuse(11).

Taquette(12), in a study with adolescents, found a statistical significance between the use of alcoholic beverages and/or illicit drugs and the variable of having an STD.

According to Oliveira(13), the abuse of alcohol and tranquilizers is one of the forms of reaction adopted by victims of violence. Alcohol consumption is one of the negative behaviors of people who have suffered violence.

The presence of smoking in the lives of adolescent offenders demonstrates not only the ease of acquiring cigarettes (denoting no mechanism of repression in the trade of this “legal” drug for adolescents), but also its effect on the health conditions of girls, reducing their immune defenses, creating physical and psychological dependence and acting as a facilitator for “illicit” drugs.

In a study on the variables tobacco, alcoholic beverages and illicit drugs, Taquette(14) found a significant association with having an STD. She also found an association between young age at first sexual intercourse and having an STD.

The use of contraceptive methods does not differ from that found in other studies related to the subject, with different theory and practice, when violence directly interferes in the negotiation of condom use and places the adolescent in a vulnerable situation in relation to her peers(15-18).

The results of the colpocytology demonstrate that the presence of an STD is an important factor in the transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and early diagnosis and treatment are desirable for this clientele exposed to STD.

In addition to raising awareness of the problem of violence in adolescence, knowledge of the profile of adolescents in conflict with the law will enable a comprehensive approach by a multidisciplinary team in serving this social stratum, as well as facilitating the adoption of public initiatives at the educational and health levels.

Understanding the factors that contribute to such disastrous results as those presented here can establish important partnerships with other health services and support networks for adolescents.

Figure 1 – Education

Figure 1 – Education Figure 2 – Presence of drugs in the family (father and/or mother)

Figure 2 – Presence of drugs in the family (father and/or mother) Figure 3 – Alcoholism

Figure 3 – Alcoholism Figure 4 – Smoking

Figure 4 – Smoking Figure 5 – Sexarch

Figure 5 – Sexarch Figure 6 – Colpocytology result

Figure 6 – Colpocytology result