INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis, a disease so old that it is almost intertwined with the history of mankind, remains a major public health problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates around 8 million new cases worldwide and almost 2 million deaths per year(19).

In Brazil, between 80 and 90 thousand new cases have been diagnosed per year in the last 10 years; this corresponds to an incidence rate of 45.5/100 thousand inhabitants. Among the federated units, Rio de Janeiro has one of the most worrying situations in the country, with around 13 thousand new cases reported in recent years, with an incidence rate of 83.4/100 thousand inhabitants(7, 8). In this state, chaotic urbanization, the high percentage of the population living in urban areas – 96.4% in 2000, the highest in the country – and deficiencies in the health system are likely justifications for the high number of cases and the high percentage in relation to the total in the country(12).

The pulmonary clinical form with positive bacilloscopy is the most common – around 60% of cases -, followed by 25% of pulmonary forms without bacteriological confirmation and 15% of extrapulmonary forms. The predominant sex is male, with two thirds of cases. By age group, the highest number is found among adults, especially those in their third decade of life(7, 8).

In children, tuberculosis presents clinically in various forms and with little characteristic clinical picture. As for adolescents, there are still few reports of clinical and laboratory presentation of the disease; however, these are generally included in the chapters on tuberculosis in childhood, which may not be a reliable portrait of the characteristics of the disease in adolescence(1, 19). In adults, tuberculosis is well described, with clinical, radiological and laboratory evidence already established.

In relation to children, adolescents are more susceptible to developing tuberculosis because of the hormonal changes and changes in calcium metabolism that occur during this phase of growth (13, 17). The time interval between the initial infection and the onset of the disease is also shorter for adolescents, when compared to that observed in individuals of other age groups (13).

The objective of the present study is to describe the demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of a group of adolescents with tuberculosis, comparing them with those of adults. The knowledge acquired may contribute to the design of new strategies for tuberculosis control in adolescence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted on a sample of tuberculosis patients treated between November 2002 and May 2007. The study included patients who were diagnosed and followed up during this period by the Tuberculosis Program of a public health unit of the City of Rio de Janeiro (Newton Bethlem Medical Care Center, located in the Jacarepaguá area). Patients

were invited to participate in the study upon diagnosis and signed an informed consent form.

Adolescents were considered to be individuals aged 10 to 19 years, and young adults were considered to be individuals aged 20 to 24 years, which are the definitions adopted by the WHO(18, 19). The characteristics of adolescents and young adults with tuberculosis (group A) were compared with those of adults also with tuberculosis (group B), individuals aged 25 to 39 years, since this is the age group with the highest incidence of tuberculosis both in Rio de Janeiro and in Brazil(7, 8).

A case of tuberculosis was one whose diagnosis was confirmed by bacilloscopy and/or culture for

Mycobacterium tuberculosis , or who presented clinical, radiological and epidemiological evidence of tuberculosis and who, after the prescription of the therapeutic regimen, evolved with significant improvement without having been diagnosed with another disease. For pulmonary tuberculosis, two clinical forms were defined: 1) positive pulmonary, for cases with bacteriological confirmation in sputum; 2) negative pulmonary, for cases without bacteriological confirmation in sputum(7, 8). For extrapulmonary tuberculosis, individuals who presented tuberculosis located in other non-pulmonary sites were considered.

The characteristics studied were demographic (sex and age), clinical (form of the disease, type of treatment, reason for termination) and laboratory (sputum bacilloscopy and culture, tuberculin skin test, anti-HIV serology). The statistical significance of the associations found was established through the chi-square test and

p

-values < 0.05. The SPSS 15 program was used to create the database and perform statistical analysis.

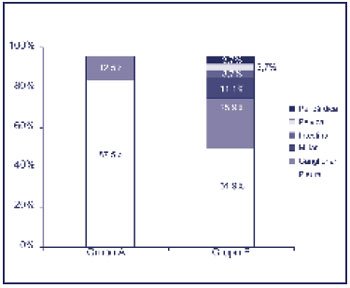

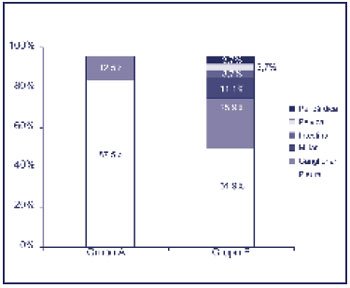

RESULTS The study included 203 patients with tuberculosis, 77 adolescents and young adults (group A) and 126 adults (group B). The most prevalent sex was male, representing 62.3% of patients in group A and 50.8% of individuals in group B (

Figure 1 ). In the analysis of this variable, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (

p = 0.109).

Figure 1 – Sex of patients according to groups

The age of the adolescents/young adults ranged from 12 to 24 years (mean of 20.2 ± 3.03 years), with 24 of them between 10 and 19 years of age and 53 between 20 and 24 years of age. The age of the adults ranged from 25 to 39 years (mean of 32.1 ± 4.37 years). Almost all of the patients in both groups came from lower social classes, reflecting the strategic location of this public health unit.

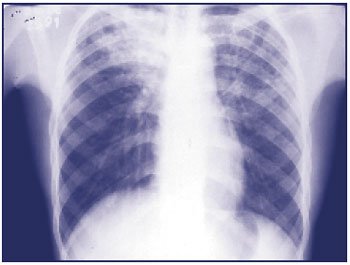

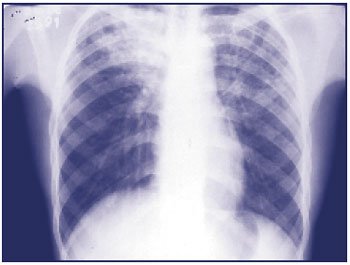

Regarding the clinical presentation of tuberculosis, no significant difference was observed between the groups (p = 0.913). The pulmonary form of tuberculosis was the most frequent in both age groups studied, having been diagnosed in 61 adolescents/young adults (79.2%) and in 99 adults (78.6%) (

Figures 2, 3 and

4 ).

Figure 2 – Clinical forms according to groups

Figure 3 – 18-year-old male adolescent complaining of cough, evening fever and hemoptysis. The sputum smear was positive for AFB. His chest X-ray showed infiltration in the upper third of the right hemithorax, in addition to a cavitary lesion in the left lung apex. AFB: acid-fast bacillus

Figure 4 – 14-year-old female adolescent complaining of productive cough, evening fever and weight loss. Positive sputum smear microscopy for AFB. His chest X-ray showed interstitial infiltration in the base of the right hemithorax. AFB: acid-fast bacillus

The distribution of patients according to the pulmonary form of tuberculosis (positive or negative) is shown in

Table 1. For this variable, no statistically significant difference was observed between groups A and B (

p = 0.523).

Extrapulmonary forms of the disease occurred in 16 individuals in group A (20.8%) and in 27 in group B (21.4%). Although pleural tuberculosis was the most frequent extrapulmonary form in both groups, there was a higher prevalence in adolescents/young adults than in those between 25 and 39 years of age (87.5%

vs. 51.9%). The distribution of these patients, according to the extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis, is shown in

Figure 5 .

Figure 5 – Extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis according to groups

Among those who underwent anti-HIV serology, the test was positive in one patient in group A (1.3%) and in nine in group B (7.1%) (p = 0.119). In sputum, bacilloscopy was positive in 35 adolescents/young adults (45.5%) and in 59 adults (46.8%), with no statistically significant difference (

p = 0.937). Regarding the tuberculin skin test result, the test was positive in 12 adolescents/young adults (15.6%) and 19 adults (15.1%) (

p = 0.744).

Table 2 shows the distribution of patients according to the complementary tests, as well as the p value .

In this case series, only one patient in each group died, while treatment abandonment occurred in seven patients in group A (9.1%) and four in group B (3.2%). Among the adolescents/young adults, three had relevant associated social conditions: one was part of the “street population”, one was an illicit drug user and one was an ex-convict. These three patients abandoned treatment.

In the sample studied, the cure rate was 88.3% and 94.4% in individuals in groups A and B, respectively. When the outcomes were grouped into “favorable” (discharge due to cure or completion of treatment) and “unfavorable” (death, abandonment or treatment failure), the groups remained without statistically significant difference (p = 0.116), as shown in

Table 3 .

DISCUSSION

Cross-sectional studies are of great value to health services, since they provide general data and correlations on the conditions of the population analyzed, and can produce measures of disease prevalence. These investigations can collaborate in the idealization and emergence of new strategies and programs for the control of the disease studied(10).

Due to its importance in public health, tuberculosis is an ancient disease that has been studied for a long time in all its aspects. Although the presentation of tuberculosis has been widely described in adults and the elderly, there are still few studies demonstrating the characteristics of this disease among adolescents(19).

Tuberculosis in adolescents is a socioeconomic and health issue worldwide, despite the lack of knowledge about it. To date, most chapters of books published on the subject refer to the presentation of tuberculosis in adolescents as being closer to that described in childhood(1). However, in the present case study – which compared adolescents and young adults (group A)

vs. adults (group B) with tuberculosis from an area on the outskirts of the city of Rio de Janeiro – it was found that the clinical and laboratory presentations and the outcome were similar in the two age groups studied.

Adolescence is the period in which endocrine and metabolic changes inherent to this phase of life occur, such as modifications in calcium and protein metabolism, various hormonal changes and the occurrence of the pubertal growth spurt(13, 17). This increases the adolescent’s susceptibility to developing tuberculosis. Research has even identified the possibility that endocrine effects may alter the adolescent’s body’s ability to control the tuberculosis bacillus, through changes observed in the immune system(4).

In the series studied of adolescents and young adults, tuberculosis was more frequent in males, which is consistent with the literature consulted(19). Furthermore, this predominance of the disease in males (62.3%) is similar to the distribution in the general tuberculosis population of the state of Rio de Janeiro (67.4%)(12). The higher prevalence in men can be attributed to biological factors, including lifestyle habits(15).

According to the results of the present case series, the most frequent clinical form of tuberculosis in both groups was pulmonary tuberculosis, a fact also observed in all other age groups(16). The hormonal changes mentioned above are probably also responsible for the evidence that tuberculosis in adolescents presents more similarly to the pulmonary form in adults, that is, with pulmonary infiltrates in the upper thirds, cavities, bronchial dissemination and more respiratory symptoms. In childhood, these symptoms are less present, and the condition is more prolonged. Symptoms such as hemoptysis and night sweats are often present in adolescents and adults, but are uncommon in children.

In some studies, the incidence of extrapulmonary forms increased with advancing age, which was not observed in our study(9). However, we found that pleural tuberculosis was much more frequent among adolescents and young adults than among adults (87.5%

vs. 51.9% of extrapulmonary forms); Pleural tuberculosis may result from the rupture of a primary subpleural focus or be secondary to a manifestation of hypersensitivity to the bacillus(6).

In the laboratory evaluation of groups A and B, we found similar rates of positive sputum smear microscopy and culture, reaction to the tuberculin skin test, and tests not performed, with no statistically significant differences. This may be explained by the fact that in adolescents, as in adults, it is easier to collect secretions to identify the bacillus; in children, this does not happen, making laboratory diagnosis more difficult.

HIV has been identified as one of the factors responsible for the increase in the number of tuberculosis cases worldwide(18). However, as our results show, only one case of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was diagnosed among adolescents and young adults, demonstrating that this is not an impacting factor in the magnitude of tuberculosis between 10 and 24 years of age. It is worth noting that the sample of individuals in this age group was small, which prevents the extrapolation of the finding to the adolescent population as a whole.

In this series of data studied, the outcome in both groups remained without statistically significant differences. However, even though group A had fewer individuals than group B, we observed more cases of treatment abandonment among adolescents and young adults, who therefore have lower adherence. This may be explained by the lack of information about the disease and the fact that adolescence is a period of profound psychosocial changes and greater emotional lability(5).

Some studies have shown that parental support and participation during the tuberculosis treatment period helps with adherence to therapy, a fact that is also related to the presence of self-esteem in adolescents(2, 3). In addition to family support, it is important for adolescents with tuberculosis to have a sense of autonomy, which can reduce the dropout rate(14).

A critical analysis of the results and limitations of the present study is pertinent. One of them is the fact that we did not obtain a sample of children with tuberculosis, which would allow direct comparison with data from adolescents and young adults. This would be interesting, since the description of tuberculosis in adolescents is frequently included in the literature together with that in children. Other limitations are the small number of patients with certain conditions (such as the pleural form of tuberculosis and HIV co-infection) and the population profile of the sample (individuals from less favored social classes), which makes it impossible to extrapolate our results.

In conclusion, the present study shows that the clinical and laboratory presentation of tuberculosis is quite similar between the adolescent/young adult group and the adult group, with the exception of the higher frequency of pleural tuberculosis in the younger age group. Treatment abandonment, detected mainly among adolescents/young adults, is a fundamental factor for strategies aimed at achieving greater adherence to antituberculosis therapy. Therefore, integrated into clinical care, greater psychological care is needed for adolescents, both by the medical team and by their families, providing them with more detailed information about the disease and its treatment.

Figure 3 – 18-year-old male adolescent complaining of cough, evening fever and hemoptysis. The sputum smear was positive for AFB. His chest X-ray showed infiltration in the upper third of the right hemithorax, in addition to a cavitary lesion in the left lung apex. AFB: acid-fast bacillus

Figure 4 – 14-year-old female adolescent complaining of productive cough, evening fever and weight loss. Positive sputum smear microscopy for AFB. His chest X-ray showed interstitial infiltration in the base of the right hemithorax. AFB: acid-fast bacillus

Figure 3 – 18-year-old male adolescent complaining of cough, evening fever and hemoptysis. The sputum smear was positive for AFB. His chest X-ray showed infiltration in the upper third of the right hemithorax, in addition to a cavitary lesion in the left lung apex. AFB: acid-fast bacillus

Figure 4 – 14-year-old female adolescent complaining of productive cough, evening fever and weight loss. Positive sputum smear microscopy for AFB. His chest X-ray showed interstitial infiltration in the base of the right hemithorax. AFB: acid-fast bacillus Figure 5 – Extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis according to groups

Figure 5 – Extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis according to groups