INTRODUCTION

Irregular or excessive bleeding is one of the most common complaints in the gynecology clinic, especially at the extremes of reproductive life, which makes it even more frequent in the daily routine of the pediatric and pubertal gynecologist. The term “dysfunctional uterine bleeding” (DUB) refers to excessive, recurrent and irregular uterine bleeding that cannot be attributed to systemic anatomical or pathological alterations(1). The normal menstrual cycle is defined as uterine bleeding that occurs every 21 to 35 days, lasting two to seven days and with a maximum blood loss of between 60 and 80 ml, since, above these values, there is damage to iron homeostasis and a decrease in ferritin(2). However, we have noticed that the search for treatment is more motivated by the perception of bleeding and the loss of quality of life – school, work and sexual activity – than by menstrual volume.

The causes of increased bleeding can be divided into organic and functional. In adolescence, the main organic causes include obstetric pathologies (abortion, hydatidiform mole, ectopic pregnancy); pathologies of the uterine cervix (cervicitis, intraepithelial lesions); sexually transmitted diseases (STD); pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); blood dyscrasias (thrombocytopenia, von Willebrand disease, leukemia); trauma; systemic pathologies (hypothyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]) and iatrogenic causes (hormonal contraception, anxiolytics, antidepressants, anticoagulants and corticosteroids)(1, 2). Uterine bleeding of functional cause, SUD, consists of a diagnosis of exclusion. It is more frequent in the first years after menarche and results predominantly from anovulatory cycles caused by the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic investigation should begin with a detailed menstrual history, including age at menarche, cycle length (

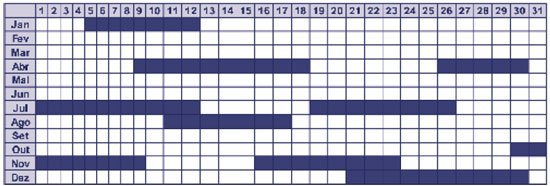

Figure 1 ), and characterization of bleeding in terms of duration, quantity, color, presence of clots, and dysmenorrhea. Given the subjectivity of assessing menstrual loss, we should attempt to quantify it using data such as the type and size of pads used, their filling (

Figure 2 ), the frequency of changes on the day of heaviest flow and nighttime changes, in addition to the size of the clots(2).

Figure 1 – Example of menstrual calendar

Figure 2 – Visual model of filling pads

A directed anamnesis helps to identify factors related to bleeding. Eating habits, exercise, weight changes, asthenia, psychosocial stress, use of legal and illegal drugs, and reports of the appearance or worsening of acne and hirsutism should be investigated. Reference to bleeding events (e.g., epistaxis, bleeding gums) alerts to coagulation disorders that may have their first clinical expression in menorrhagia. Von Willebrand disease, for example, has an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population and increases to 5% to 24% in patients with menorrhagia(2). In addition to the menstrual characteristics of the mother and sisters, the family history should investigate hemopathies, especially alterations in platelet function, and endocrine diseases such as obesity, thyroid disease, and hyperandrogenism. Information about sexual activity, use of contraceptive methods, and signs and symptoms of STDs should be obtained privately, respecting physician/patient confidentiality.

Ectoscopy and physical examination should be performed. The following are assessed: body mass index (measurement of height and weight [BMI] = weight/height ±

2 ); Tanner stages in the breast and pubis; signs of hyperandrogenism (acne, hirsutism, clitoral hypertrophy); signs of coagulation disorders (petechiae, ecchymosis and hematomas); signs of anemia (cutaneous and mucous pallor, bluish sclera) and other organic alterations (through striae,

acanthosis nigricans and goiter). The patient’s heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) are checked while sitting and standing. The presence of orthostatic hypotension indicates hemodynamic repercussions of the condition. Anemia can also be identified through brief cardiac auscultation with a pancardiac holosystolic murmur.

In patients without sexual activity, the gynecological examination should include a genital inspection looking for signs of trauma and foreign bodies. Sexually active women should undergo a complete examination, including a Pap smear and bimanual examination to assess the size of the uterus and adnexa, pain or signs of pregnancy.

Initially, we request a complete blood count, coagulation test and pelvic or transvaginal ultrasound (USG). In cases of primary menorrhagia associated with clinical signs of blood dyscrasia, von Willebrand disease should be investigated. In sexually active adolescents, the beta fraction of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) is mandatory to exclude pregnancy; cervical cytology to screen for intraepithelial lesions and screening for STDs including Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea, important causes of cervicitis and PID. Additional tests are requested according to the specific clinical picture or the results of preliminary tests (e.g.: hormone levels, liver and kidney function).

CONDUCT

After ruling out the main organic causes of bleeding, the treatment is individualized according to age, menstrual history and severity of bleeding. Cases of irregular bleeding of low intensity usually occur in the first years after menarche. There is uncertainty regarding the frequency, duration and volume of the catamenia, but there are no symptoms; the hematocrit (Hto) remains above 35% and the hemoglobin (Hb) is 11 g/dl. The patient is asked to fill out a menstrual calendar regularly (Figure 1) and to return in three months, with guidance and a diet rich in iron and proteins being indicated(1). If the irregular pattern persists, progesterone is used in the second phase of the cycle to prevent excessive proliferation of the endometrium.

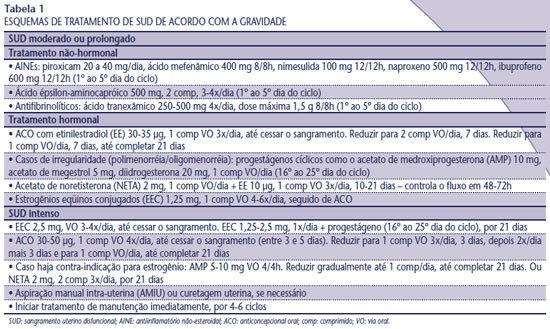

Non-hormonal treatment of menorrhagia is initiated with prostaglandin inhibitors (

Table 1 ) and the drug of choice is mefenamic acid due to its greater efficacy and lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects(3). If the response is insufficient, an antifibrinolytic agent such as tranexamic acid can be used. Epsilon-aminocaproic acid, previously classified as an antifibrinolytic agent, actually corrects abnormal platelet function. Thus, its effect on menstrual flow is comparable to that of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and not to that of antifibrinolytics, which act by inhibiting endometrial plasminogen activators. Therapy with tranexamic acid reduces bleeding significantly more than other drugs, including NSAIDs, second-phase progestins, and epsilon-aminocaproic acid(3, 4). Its effect translates into a reduction in catamenial volume and the number of pads used per cycle, in addition to improving the quality of the patient’s sexual life. There are no reports of significant side effects or increased risk of thromboembolic events with its use(4).

In cases of anovulatory bleeding, with Hto maintained between 25% and 35% and Hb between 9 and 11 g/dl, combined contraceptives are the treatment of choice, especially in sexually active young women. However, progestogens in the second phase of the cycle (10 days) are prescribed more often for menorrhagia. The treatments have similar results among themselves and when compared to regular NSAIDs (5, 6). If there is profuse bleeding, extending the use of progestogens for 21 days is more effective in reducing blood loss (1, 5). Anemia should be corrected with iron replacement and maintenance of continuous hormonal therapy until Hb > 11 g/dl.

In acute SUD, immediate interruption of bleeding and evaluation of hemodynamic repercussions are necessary. In cases of severe anemia (Hto < 25% and Hb < 8 g/dl) with hemodynamic instability, hospitalization, stabilization and estrogen therapy are recommended; replacement of blood products and uterine curettage or manual intrauterine aspiration (MVA) are evaluated. The injectable formulation of conjugated equine estrogens for intravenous use, considered the first choice of therapy, is no longer available in the Brazilian market. According to Machado, intravenous estrogen is not more efficient than oral estrogen, therefore conjugated equine estrogens 2.5 mg orally are prescribed four times a day, for 24 hours, with interruption of bleeding within 48 hours (7) (Table 1).

After controlling acute phase bleeding, it is essential to start maintenance treatment immediately for four to six cycles (

Table 2 ). It is important to inform the patient that breakthrough bleeding may occur when restarting the cycles and that therapy must be maintained. Bleeding will become regular after a few cycles, allowing hormones to be suspended. However, in the case of sexually active adolescents, we can continue taking combined oral contraceptives (OC).