INTRODUCTION

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune, multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown origin that is characterized by the presence of several autoantibodies

1 . It is described in the literature that lupus patients are more likely to develop cardiovascular events, although its mechanism is still unknown. It is proposed that lupus itself, as an inflammatory disease, triggers chronic activation of the immune system, with greater stimulation of inflammatory cytokines, leading to the formation of premature atherosclerosis

2 .

Modifiable risk factors for atherosclerosis in adolescents with SLE include obesity, systemic arterial hypertension (SAH), insulin resistance,

diabetes mellitus , dyslipidemia (elevated low-density lipoprotein

( LDL), increased triglycerides (TG) and low high-density lipoprotein

( HDL), smoking, increased homocysteine and interleukins (IL-1), (IL-6) and (IL-8)

3 . Non-modifiable factors include age, sex, genetics and family history. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors are more prevalent in lupus patients, resulting in changes in the integrity of the vascular endothelium, with presence in the active or remission phase of the disease

4 .

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is a set of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, which include abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia

5 . MS has become a common disorder in Brazil, affecting approximately 7.5% to 30% of the Brazilian population, and is considered a major public health problem

6 .

A study conducted with lupus patients showed a high prevalence of excess weight, which increases the chance of developing MS by 50%

7 . This reinforces the extent to which these individuals are susceptible to developing metabolic disorders throughout therapy, and early detection of metabolic changes is of great importance, enabling measures to stimulate improvement in quality of life and health promotion

8 . In addition, there is a lack of studies on the metabolic profile of adolescents with SLE. In view of this, the objective of this study was to determine the frequency of MS and its components in adolescents with SLE.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the rheumatology outpatient clinic of the Center for Studies on Adolescent Health at Pedro Ernesto University Hospital. All adolescents diagnosed with SLE participated in the study

9of both sexes, aged between 10 and 19 years, who signed the informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were the inability to stand upright or lie on their backs to perform the nutritional assessment. The anthropometric measurements taken were weight (kg), measured using a

Micheletti

digital scale with a capacity of 200 kg and a graduation of 0.05 kg, and height (cm) using a Sanny stadiometer fixed to the wall

, with an accuracy of 0.1 cm. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the weight (kg)/height (m2) ratio

, with subsequent classification of nutritional status, performed using criteria established for adolescents by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2007

10 . To measure waist circumference (WC), an inelastic millimeter tape was used at the midpoint between the last fixed rib and the upper edge of the right iliac crest, measured at the end of a normal expiration. To classify WC, the Freedman parameters

11 were used . The criteria for diagnosing MS were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the

International Diabetes Federation (IDF)

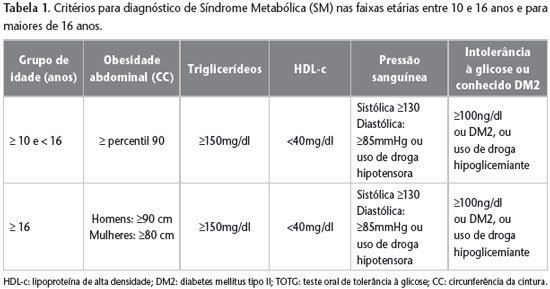

12 as shown in Table 1.

Patients were selected into groups with one, two or more than two components of MS. The diagnostic criteria referred to by the IDF (2007)12 were abdominal obesity – which includes increased waist circumference according to percentile > 90 for age and sex, triglycerides > 150mg/dl, HDL < 40mg/dl, systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 and diastolic ≥ 80mmHg, or use of hypotensive medication, fasting blood glucose ≥ 100mg/dl or use of hypoglycemic medication. The hexokinase enzymatic method was used to assess fasting blood glucose, and the enzymatic colorimetric method was used to measure triglycerides, total cholesterol and HDL. Laboratory tests were performed in the hospital’s own laboratory after a twelve-hour fast was indicated.

Data on education and family income were extracted from the patients’ medical records. Blood pressure (BP) was measured on the right arm with an appropriate cuff, determined by the brachial circumference (BC), covering approximately 80% of the distance between the olecranon and the acromion, through the oscillometric method, using the Omron 705-IT

r equipment . Three measurements were taken at three-minute intervals, after the adolescent had rested for five minutes. Adolescents with systolic and/or diastolic BP below the 90th percentile for height, sex, and age were considered normotensive; those with borderline BP were considered hypertensive if systolic and/or diastolic BP was between the 90th and 95th percentiles; and those with hypertensive if systolic and/or diastolic BP was above the 95th percentile

13 . The International Physical Activity Questionnaire

for Older Children

(PAQ-C) was applied to investigate the level of physical activity. Those who obtained a score > 300 minutes/week were classified as active and those with <300 minutes/week were classified as inactive. Individuals with a level of physical activity greater than 2,100 minutes/week were excluded from this variable

14 . The SLEDAI (

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index ) index was used to determine disease activity in adolescents with SLE

15 and a cutoff value of ≥ 3 was adopted to classify disease activity. The use or non-use of corticosteroids and antimalarials was analyzed, adopting as the cutoff point the continuous administration of at least one month of use

16 . For data analysis, the data were first stored in an Excel spreadsheet version 7. Subsequently, they were analyzed using the

software

STATA version 10. Continuous variables were described by means of mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables by proportion. The variables were tested using the Kolgomorov-Smirnov test to verify whether they had a normal distribution. Those with a normal distribution were compared using the

Student ‘s t-test , and those with a nonparametric distribution were compared using the

Mann-Whitney test . For categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. For all analyses, a value of (P<0.05) for significance was adopted.

RESULTS

A total of 42 adolescents were analyzed, 37 girls (88%) and 5 boys (12%). The mean age was 16.8 ± 1.5 years. Regarding the classification of nutritional status, the highest number of eutrophic individuals was obtained

(57.1%), followed by obese (26.2%), overweight (12%) and underweight (4.7%). It was observed that 24 adolescents used corticosteroids (57.2%) and 37 antimalarials (88.1%). Regarding disease activity, the SLEDAI index was altered in 23 patients (54.7%). The other results are shown in Table 2.

In the individual analysis of the components of MS, it was evident that 15 adolescents (35.7%) presented two risk factors, 13 (30.9%) presented one risk factor and no patient presented the four components used in the IDF criteria. MS was diagnosed in seven patients (16.7%). Of these, five (71%) were female and two (29%) were

male. Of the seven adolescents who were diagnosed with MS, all were in the age range of 17 to 19 years, and six of them (85%) had a family income ≤ 3 minimum wages. In this same context, it was observed that within the group with MS, five (71%) presented SLEDAI ≥ 3. As shown in Table 3, the mean BMI was significantly higher in individuals with MS (

p=0.006 ) when compared to the mean of those without MS (28.4 kg/m2

vs 23.6 kg/m2

) . For WC, a statistically significant mean (

p=0.0006 ) was observed in those with MS. As for fasting blood glucose, it was higher in adolescents with MS. A relevant aspect in this study was the percentage of sedentary adolescents in the study (62.5%), and of these, 24% presented MS. Table 4 shows the frequency of the MS components, where high WC, hypertension and low HDL were the most prevalent.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the frequency of MS was 16.7%. Ford et al. found a prevalence of 4.5% of MS using the IDF as a diagnostic reference in a population of healthy American adolescents

17 . Another study conducted with 79 obese adolescents found a prevalence of 45.5% of MS

18 . Regarding the diagnostic criteria for MS stratified in relation to nutritional status, in the present study it was confirmed that MS was more prevalent in obese individuals (27.3%).

The percentage of excess weight measured in the study was 38.2%. The research carried out by Mina et al. with children and adolescents with SLE showed a prevalence of 25% of obesity in a sample of 202 patients, where this metabolic disorder was correlated with a negative impact on quality of life, including reduced physical capacity and social and emotional dysfunction

19 . The study by Sinicato et al. revealed a frequency of 31% of adolescents with lupus with obesity, associated with high levels of inflammatory cytokines, with statistical significance for TNF-alpha

20 .

The treatment of SLE is individualized with regard to the medications administered and their dosages, depending on the degree of organ or tissue involvement

21 . Glucocorticoids are the drugs most commonly used in the treatment of SLE, and their daily doses will differ according to the individualized protocol

22 . According to a study carried out by Mok et al., who evaluated 29 lupus patients for six months, it was observed that those who used high doses of corticosteroids had a correlation with changes in BMI, increased body fat percentage and reduced lean mass

23 . In this study, more than half of the adolescents with lupus used corticosteroids and the majority used antimalarials. A study carried out by Reis

et al. 24 found a frequency of 93.7% of prednisone use and 69.6% of antimalarials.

The frequency of adolescents considered active according to IPAQ-C was 37.5% (n=15). Considering the total sample, approximately 62.5% (n=25) of the adolescents analyzed were considered sedentary, and of these, 24% (6) had MS, corroborating the importance of physical activity in preventing risk factors for MS. The literature reinforces the importance of improving the body composition of lupus patients with physical activity, as well as exercise resistance, better cardiorespiratory capacity and quality of life, without stimulating disease activity

25 .

The SLEDAI index, used to classify disease activity, was altered in more than 50% of the sample, indicating disease activity. In a study conducted with women with lupus at the University Hospital of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (HU-UFMS), a 22.1% alteration was observed

26 .

After analyzing the components separately, WC was altered in 31% of adolescents with lupus. It is assumed that elevated WC becomes an aggravating factor of MS in children and adolescents, and could be used to identify the risk of CVD in clinical practice

27 .

The mean fasting blood glucose levels remained higher in adolescents with MS when compared to those without MS. A study conducted by Sánchez-Pérez et al. verified the presence of IR through the analysis of HOMA-IR and C-peptide in individuals with SLE, when compared to the control group

28 . Although our data did not verify IR in adolescents with lupus, it is known that it is important to periodically monitor this parameter as a way of preventing chronic non-communicable diseases, such as

diabetes mellitus 29 .

High levels of LDL cholesterol and low levels of HDL are closely related to the process of atherogenesis

30 . However, this study did not find a significant value that related HDL to MS. However, LDL and total cholesterol (TC) levels, although not part of the diagnosis recommended by the IDF, remained high in those with MS. The presence of dyslipidemia worsens the progression of atherosclerosis, especially when TC, LDL and TG levels are high and HDL levels are low

31 .

SAH is an independent risk factor for the occurrence of atherosclerotic vascular damage in lupus. Rahman et al. described an important association between SAH, hypercholesterolemia and vascular events in patients with SLE

32 . In the aforementioned study, 50% of the individuals evaluated presented changes in BP. In a study by Telles et al., the most prevalent risk factor for CVD in lupus patients was hypertension, present in 48.8% of the individuals studied

33 .

CONCLUSION

In the present study, it was possible to conclude that the individuals who presented the highest prevalence of MS were female adolescents, aged between 17 and 19 years, attending high school, with a family income of less than three minimum wages, obese, using antimalarial drugs, sedentary and with a time since diagnosis of the disease ranging from one to three years. As a limitation of the study, we can highlight the absence of individual doses of corticosteroids used by the adolescents during the study.

Metabolic syndrome is a serious public health disorder, and it is extremely important to monitor individuals at metabolic risk so that prevention and control measures can be established. Particularly, the young population with SLE may present metabolic dysfunctions with significant complications throughout the therapeutic trajectory, and early monitoring alleviates future complications, especially the prevention of NCDs. Additionally, healthy lifestyles, such as physical activity and a balanced diet, are essential for maintaining adequate nutritional status. Therefore, this study warns of the need to screen for MS in adolescents with SLE, so that there is more attention to the early detection of metabolic abnormalities.