INTRODUCTION

Chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the main causes of death worldwide, with emphasis on diseases of the circulatory system, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease, with the main associated factors being tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol consumption

1 .

During adolescence, with the various biopsychosocial and behavioral changes specific to this phase

2 , there is a greater vulnerability to the insertion of these risk behaviors early on, which can extend throughout the life cycle, considering that young people who adopt risk behaviors, as they advance in age, tend to have a greater predisposition to NCDs

3 .

In this context, the reversal of the NCD epidemic precedes a comprehensive population approach, with preventive and care interventions from intrauterine life to adolescence, with the purpose of minimizing risks in all phases of life

4 , considering that modifying bad health habits already established in adult life are difficult goals to achieve. However, healthy habits acquired in childhood and adolescence that are continued into adulthood can contribute to the primary prevention of NCDs

5 .

Thus, the multidisciplinary team faces the challenge of implementing effective, long-lasting, and viable strategies in the field of public health that lead to the adoption of a healthy lifestyle in the first two decades of life

6 . Studies to identify population groups at risk and factors that influence poor health habits in childhood and adolescence are essential for the development of policies and programs that will intervene in the control of chronic diseases in adulthood

7 .

Given the need to identify risk factors in the adolescent population in order to create, improve, and evaluate health policies and programs that will prevent the incidence of NCDs, the present study aims to identify the main modifiable risk factors for individual and associated NCDs in Brazilian adolescents.

METHODS

An integrative review of the literature was conducted with the purpose of synthesizing the results obtained in research that addresses a theme or issue in a systematic, orderly, and comprehensive manner

8. The question that guided the review was: What modifiable risk factors for NCDs have been identified and how are these risk factors associated according to research conducted with the Brazilian adolescent population? To identify published studies on this issue, an online search was conducted in the following databases: Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS),

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) and

Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO). The descriptors used for the search were: “Risk Factors” AND “Adolescent” AND “Chronic Disease”. The following inclusion criteria were used to select the articles: research conducted in Portuguese, Spanish or English, with Brazil as the reference country and published between 2011 and 2016. This time period was determined by the creation and implementation in 2011 of the Strategic Action Plan to Confront Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases in Brazil 2011-2022

4 . The articles were selected after careful reading of the titles and abstracts. Those not related to the adolescent age group, non-epidemiological studies, and those whose title and abstract were not within the objectives proposed for the review were excluded.

The search strategy identified 51 studies in the LILACS, MEDLINE and SciELO databases. After analyzing the titles and abstracts, regarding the eligibility criteria, 48 studies were excluded: one due to repetition in LILACS and SciELO, and 47 because they were outside the proposed theme, leaving three documents to compose this review (Figure 1).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

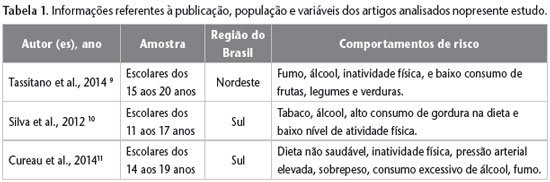

The studies analyzed were cross-sectional with a probabilistic sample of adolescent students. The first study selected, conducted by Tassitano et al.

9 , aimed to verify the aggregation of the four main risk behaviors (smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity and low consumption of fruits, vegetables and greens) in 600 adolescents aged between 15 and 20 years in a municipality located in the Northeast of Brazil. The second, carried out by Silva et al.

10 , aimed to estimate the prevalence and patterns of risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases according to socioeconomic level and age in a sample of 1675 adolescents aged between 11 and 17 years in a municipality in the South of the country. In the third article, Cureau et al.

11evaluated the grouping of behavioral and biological risk factors for NCDs (unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, overweight, and high blood pressure) associated with sociodemographic variables in 1,132 adolescents aged 14-19 years from a city in the southern region of Brazil.

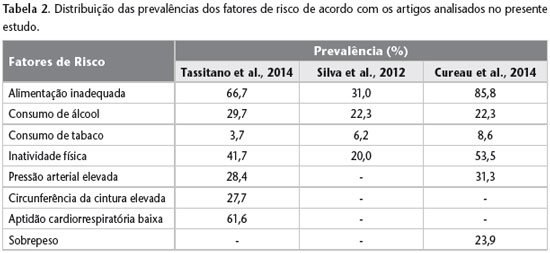

The three documents were presented in the format of original articles; the research participants were between 11 and 20 years old. Two studies were conducted in the southern region of Brazil and one in the northeast region. Regarding the year of publication, one article was published in 2012 and the other two in 2014. The main risk behaviors for NCDs investigated in the adolescent population were smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, and inadequate diet and their respective prevalences (Tables 1 and 2).

In the first article, to verify the consumption of fruits, vegetables and legumes, the frequency of consumption was used by the number of days per week and the amount of servings ingested each day. Adolescents who reported consuming less than five servings per day were considered exposed to the risk factor

9 . In the second study, diet was measured based on total caloric intake of fats, with fat intake being considered high by adolescents who had a percentage greater than 30%

10 . The third study investigated the frequency of intake of fifteen foods rich in fats and nine foods rich in fiber, classified from 0 to 4, in which 0 (zero) corresponded to low frequency and 4 to high frequency. Adolescents who scored 27 points for foods rich in fats and 20 or less points for foods rich in fiber were considered to have unhealthy diets

11 .

According to Table 2, the risk factors related to inadequate nutrition, being high in fat and low in fiber, are the most present in the adolescent populations studied, corresponding to 66.7% and 85.8% in the first and third studies, respectively.

Tassitano et al.

9 estimated the level of physical activity (PAL) through the number of minutes per day and times per week that adolescents performed moderate to vigorous physical activity (PA) in various areas, namely: leisure, occupation, domestic activities and transportation. Adolescents who reported having performed less than 300 minutes of PA per week were considered exposed

9 , a cutoff point also established by Cureau et al.

11 using two instruments aimed at having an overall view of the PA performed during the week

11 . Silva et al.

10 used an instrument in which adolescents were asked to recall the PA performed on three days of the last week, two weekdays and one weekend day. The days were divided into 36 periods of 30 minutes each, and the intensity was assessed in 30-minute blocks using a scale of one to nine in which each number represented an activity and how the adolescent would be performing such activity. Energy expenditure was calculated by the amount of time spent in each period multiplied by the metabolic equivalent value, with the 1st quintile of energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day) being classified as least active

10 .

Regarding tobacco use, the authors considered adolescents who reported having smoked in the last week

9 or in the last month

10 ,

11 to be exposed., there is a consensus regarding the classification of exposed individuals regardless of the number of cigarettes smoked. With regard to the consumption of alcoholic beverages, the first study considered as an exposure factor adolescents who reported drinking alcoholic beverages on at least one day in the previous week

9 . The second study considered the consumption of one dose of alcoholic beverage in the last thirty days

10 , and the third study classified as excessive consumption the report of ingesting five or more doses of alcohol, at least, on one occasion in the previous month

11 .

The variable blood pressure (BP) was analyzed by two studies following the same protocol, the measurement was performed twice on the adolescent’s right arm with a five-minute interval. For adolescents under 18 years of age, values that were above the 90th percentile for sex, age and height were considered high BP. For those over 18 years old, Silva et al.

10 used the cutoff point of 120×80 mm Hg, while Cureau et al.

11 considered 130×85 mm Hg as the cutoff point.

Only the second study analyzed the variables waist circumference (WC) and cardiorespiratory fitness. The values obtained through WC measurement were classified as normal or elevated according to sex, age and skin color. WC is a predictor of cardiovascular diseases and dyslipidemia. To measure cardiorespiratory fitness, the

Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER) test was used. When the student stopped due to exhaustion or was unable to maintain the required speed, the test was ended. To categorize fitness levels, the number of complete laps performed and the criteria proposed in the FITNESSGRAM manual, from the

Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research, for gender and age were considered, classifying as low or adequate/high fitness

10 .

When the association of risk factors was carried out, in the study developed by Tassitano et al.

9 , it was found that there is a greater association of one or two risk factors for NCDs in the adolescent population. When the three behaviors were grouped together, smoking, alcohol and physical inactivity stood out among boys; and among girls, smoking, alcohol and low fruit consumption stood out. The study also carried out an aggregate comparison of two risk behaviors between boys and girls. The prevalence of the combination of smoking and alcohol consumption was observed, as well as smoking and physical inactivity for boys. Among girls, smoking and alcohol consumption stood out

9 .

When aggregating risk factors for NCDs in the study developed by Silva et al.

1019.0% presented two or more unhealthy behaviors and 32% presented biological risk factors (high WC and BP/low respiratory fitness). When the prevalence of tobacco and alcohol consumption was combined, it was 4.1 times higher for boys and 2.2 times higher for girls when compared to the expected value. When combining the prevalence of tobacco consumption, alcohol and high fat composition in the diet, it was 4.7 times higher than expected for boys and 3.5 times higher than expected for girls. The combination of high WC, high BP and low cardiorespiratory fitness were respectively 85 and 69% higher than expected for boys and girls

10 .

The combination of risk factors in the study developed by Cureau et al.

11 identified 2, 3 and 4 or more risk factors, with their prevalences being respectively 40.9%, 23.1% and 11.5%. The highest prevalence identified corresponded to the combination of unhealthy diets and physical inactivity, representing a prevalence 32% higher than expected. When stratified by sex, the combinations with values above the expected were unhealthy diet, excessive alcohol consumption and smoking for boys. For girls, the combinations were stronger for unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, excessive alcohol consumption and smoking

11 .

Cureau et al.

11 found in their population of adolescents living in the municipality of the southern region of the country, 75.5% with more than one risk factor for NCDs, a higher percentage in relation to those found in the studies carried out by Tassitano et al.

9 and Silva et al.

10 as shown in Table 3.

It was also identified that adolescents with higher socioeconomic status presented up to three risk factors

9 ,

11 . Other factors such as being married or having a partner, studying during the day and not attending physical education classes presented a greater risk for exposure to three or more health risk behaviors. In the three articles analyzed, the authors reported that older adolescents have a higher prevalence of risk behaviors. There is an increase in risk factors for NCDs with advancing age, and this is associated with lifestyle, which in adolescence is strongly influenced by social life, local culture, peers and fashion trends, with direct consequences for the adoption of habits that can perpetuate throughout life

9-11 .

The three studies used different instruments to collect risk factors for NCDs: Tassitano et al. used the COMCAP Questionnaire, with questions related to lifestyle, general information (sociodemographic issues and work) and health (eating habits, physical activity, risk behaviors,

preventive behaviors and health perception)

9 ; Silva et al. used three instruments – The level of physical activity and food consumption were collected through recalls, tobacco use and alcohol consumption were collected through questions based on the

US Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire, to assess the socioeconomic level the criteria proposed by the Brazilian Association of Research Companies (ABEP) were used

10 . Cureau et al. had the level of physical activity and food consumption collected through recalls, with tobacco use and alcohol consumption collected through questionnaires, with reference in the article to the

US Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire and criteria proposed by ABEP

11 .

The authors of the three selected articles suggest approaches to associated risk factors through health promotion among young people, which could occur in two different ways: interventions aimed at two or more health risk behaviors to investigate whether this would reduce their prevalence, and intervention aimed at only one risk behavior, in order to explore the impact on other combined risk factors, for example: which combinations of risk behaviors are likely to change the others?

9-11

All three selected articles agreed on the creation of health policies and programs that can reduce the prevalence of these factors through health actions during adolescence so that these habits can be modified and reflected in adult life

9-11 . Therefore, it is possible that the school environment is a favorable environment for identifying this lifestyle, since it is in this space that this population is most easily found.

It was considered relevant to public health to investigate how these risk factors combine and what their distribution is in different economic classes, since this information fosters intervention strategies aimed at reducing health problems in the young population.

CONCLUSION

In view of these results, it was possible to perceive the need to perform an analysis of risk factors for chronic diseases such as: eating habits, physical activity and consumption of alcohol and other drugs in the adolescent population, since these habits influence the quality of life and the incidence of NCDs. The presence of more than one risk factor for NCDs in adolescents and the association with sociodemographic conditions were also observed. Further studies of these factors are needed to identify strategies that aim to reduce these behaviors during adolescence, covering not just one but several factors.