Background: Risky play, characterized by adventurous and uncertain activities, is essential for children’s development, fostering resilience, confidence, and problem-solving skills. However, parental attitudes toward such play vary widely, influenced by cultural norms, personal experiences, and safety concerns. This study aims to measure the levels of parental tolerance for risky play, identify factors that contribute to variations in this tolerance, evaluate children’s sensory environments, and examine the relationship between parental tolerance of risky play and the attributes of sensory environments. Methods: A descriptive correlational study design was used. The current study was conducted in eight primary schools in the Karbalaa city center, Iraq. A total of 480 primary school students of both sexes in the first, second, and third stages were randomly selected. A validated questionnaire consisting of three parts was used. Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied to analyze the results using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26. Results: The results reveal that 49.6% of parents have a moderate tolerance for risky play. Both parents are predominantly in the 30–39 age range, with over half of the fathers (54.2%) and nearly half of the mothers (47.3%) falling within this category. Mothers show a higher proportion having completed intermediate school (27.7%), while fathers are most frequently graduates of primary school (26%). Most of the children (65%) fall within the 6–7 age range. Conclusions: Less than half of the parents demonstrated a moderate level of tolerance for risky play. The sensory environment emerged as a crucial factor, having a significant direct positive effect on parental tolerance for risky play. Recommendations: Interventions and educational materials should be designed with varying literacy levels and educational backgrounds in mind. This will ensure that information on risky play and sensory environments is accessible and impactful for all parents. Future research should explore the causal mechanisms between sensory environments and parental tolerance through longitudinal or interventional studies.

Risky play has been shown to significantly contribute to physical, emotional, and cognitive development in recent studies on childhood development. According to Sandseter [1], risky play is characterized as exhilarating and thrilling play activities that carry a risk of bodily harm, such as climbing, jumping from heights, rough-and-tumble play, or wandering unattended. This form of play enables children to test their limits, develop motor coordination, foster independence, and build resilience [2]. However, societal changes have resulted in more parental control and fear-based restrictions, reducing children’s opportunities to participate in risky activities, even though there is growing evidence of its advantages [3]. Parental tolerance, or lack thereof, for risk in children’s play is at the core of this trend. Such play opportunities are more likely to be restricted by parents who feel that the environment is dangerous or overwhelming, which can affect whether or not children participate in experiences that are good for their development [4]. The impact of the sensory environment on parents’ tolerance of risky play is a crucial area that has not received enough attention, despite the fact that a lot of research has looked at parental attitudes and risk perception. Psychological comfort and decision-making are significantly influenced by sensory environments, which are defined by stimuli like temperature, lighting, sound levels, and spatial organization [5].

Calm, minimally stimulating, and controlled sensory input environments are referred to as chilled sensory environments. Parents may feel more at ease and be more willing to allow risky play in such settings since they reduce anxiety and foster a sense of control [6, 7]. Parents may view risky play as more manageable and less dangerous if they are less overwhelmed or overstimulated by their environment. Additionally, new research highlights the importance of taking an ecological perspective on risky play, taking into account not only social and individual aspects but also the physical and sensory aspects of play environments [8]. For instance, Sobel [9] contends that play spaces that are naturally occurring and carefully planned, frequently devoid of sensory chaos, promote both adult trust and child agency. In a similar line, kids who play in cool settings might behave more responsibly, which comforts parents and raises their risk tolerance.

The relationship between parenting style and environmental design implies that risk perception is both an internal assessment and a reaction to external sensory cues. This study, therefore, seeks to explore the relationship between parental tolerance of risky play and the presence of a chilled sensory environment. By focusing on how sensory-regulated environments influence parental perceptions and decisions, this research addresses a critical gap in the literature and extends understanding of how to design spaces that support healthy risk-taking in children. Findings may inform early childhood education, urban playground design, and parental guidance practices to strike a balance between safety and developmental freedom. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the connection between the availability of a calm sensory environment and parental tolerance of risky play. This study fills a significant gap in the literature by concentrating on how sensory-regulated environments affect parents’ perceptions and choices. It also advances knowledge about how to create environments that encourage children to take healthy risks. In order to balance safety and developmental freedom, the findings may influence parental guidance techniques, urban playground design, and early childhood education.

The present study employed a descriptive correlational design. The study was carried out from 12 November 2024 to 15 May 2025 to examine the statistical relationship between two or more variables without the researcher manipulating or controlling any of them. It looked at the relationship between “parental tolerance of risky play” and the “chilled sensory environment.”

The current study was conducted in eight primary schools in the Karbalaa City center, Iraq (four private schools and four public schools). These schools were randomly selected from the total number of schools in the Karbalaa City center.

The study sample included primary school parents. Using a probability (simple random sampling) method, 480 primary school students of both sexes in the first, second, and third stages were selected for the study. The information-gathering procedure was completed over a two-month period, from 4 February to 4 April 2025.

The inclusion criteria involved parents of selected primary school children in the first, second, and third grades in the selected schools who agreed to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria involved parents of primary school children who did not agree to participate in the study.

Data were collected using a self-reported questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part included the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics such as parents’ age, parental level of education, occupation of the household head, monthly income, number of children, child’s gender, child’s age, school type, and grade. The second part included a developed version of a five-point Likert scale measuring factors affecting risk tolerance, ranging from (1 = Never a factor, 2 = Rarely a factor, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Sometimes makes me say no, and 5 = Definitely makes me say no). The third part included a developed version of a 15-item Likert scale measuring participation and sensory environment, ranging from (Never = 1, 2 = A little, 3 = Somewhat, 4 = A lot, 5 = Shares too much).

The content validity of the study was assessed by a panel of 10 experts in the field of community health nursing. The modified and newly developed items were pilot-tested on a separate group of 18 participants to assess their internal consistency. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.93 for the factors affecting parents’ tolerance scale and 0.82 for the chilled sensory environment scale, indicating high levels of reliability.

The researcher used a self-reported questionnaire as the main method of data collection. After obtaining approval and agreement from the General Directorate of Education in Karbalaa Governorate and the selected primary schools in Karbalaa City center, the Arabic versions of the questionnaire were distributed to the selected children. After obtaining consent, the children returned the questionnaire filled out by their parents the following day.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Descriptive statistics, frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were used to describe the demographic characteristics. Mediation analysis of the effect of the sensory environment (SE) on parents’ tolerance was also conducted.

The results presented in Table 1 show the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics. Concerning parents’ age, the results indicate that both parents are predominantly concentrated in the 30–39 age range, with over half of fathers (54.2%) and nearly half of mothers (47.3%). However, mothers have a markedly higher average age (39.8 ± 7.7 years) compared to fathers (35.2 ± 6.8 years). Regarding the parental level of education, the results highlight disparities in educational attainment between mothers and fathers, with distinct trends across education levels. Mothers show a higher proportion in intermediate school (27.7%), while fathers are more frequently primary school graduates (26%). The findings show that nearly half of household heads (48.5%) are employees, while 47.7% rely on informal or freelance work. Income distribution highlights economic instability, with 47.7% earning \(\leq\)600,000 Iraqi Dinar monthly and only 4.6% exceeding 1.5 million. Family size trends toward smaller households, as 61.9% of families have 1–3 children, while larger families (7+ children) are rare (2.9%). Sex distribution is perfectly balanced (50% male, 50% female). For child age, the results reveal a predominantly young sample with a mean age of 7 ± 0.8 years, where 65% fall within the 6–7 age range. School enrollment shows equitable representation across public and private institutions (50%). Each grade distribution is uniform, with equal proportions in first, second, and third grades (33.3% each).

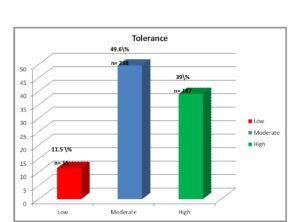

The findings in Table 2 indicate that parents’ tolerance for risky play is significantly influenced by various fears and beliefs, with certain concerns standing out as particularly strong. The highest-rated factors contributing to reluctance include fear of child injury (M = 3.97, SD = 1.269), fear of harm by others such as kidnapping (M = 3.81, SD = 1.479), fear of being unable to rescue the child in case of an emergency (M = 3.74, SD = 1.439), and gender-related beliefs about risky play (M = 3.69, SD = 1.395). These results suggest that safety concerns, protective instincts, and societal norms play a crucial role in shaping parental attitudes. While some fears, such as legal consequences (M = 2.90, SD = 1.562) and negative judgment from others (M = 2.57, SD = 1.443), are rated lower, they still reflect a moderate level of influence. Figure 1 reveals that 49.6% of parents have moderate tolerance and 39% have high tolerance regarding risky play for their children.

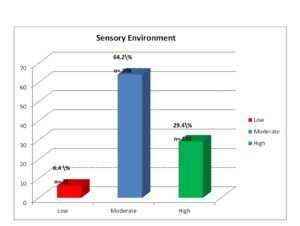

The findings in Table 3 indicate that children’s sensory environment experiences are generally assessed at a moderate level across all activities, with no extreme difficulties or ease reported. Among the assessed activities, mealtime with family members (M = 3.55, SD = 1.099) and playing with siblings/children at home (M = 3.53, SD = 1.195) were rated slightly higher. Conversely, bathing (excluding hair washing) received the lowest rating (M = 2.83, SD = 1.270). Other tasks such as sleeping (M = 3.48, SD = 1.141), toileting (M = 3.47, SD = 1.079), and brushing teeth (M = 3.39, SD = 1.060) also showed moderate assessments. Figure 2 reveals that 64.2% of children experienced a moderate sensory environment.

Table 4 indicates that the sensory environment (SE) has a significant direct effect on parents’ tolerance (PT) (\(\beta = 0.2252\), \(p = 0.0029\)), suggesting that a more accommodating sensory environment positively influences parental tolerance.

| No. | Variables | Groups | Mother | Father | |||

| F | % | F | % | ||||

| 1 | Parents age | 20 – 29 | 24 | 5 | 100 | 20.8 | |

| 30 – 39 | 227 | 47.3 | 260 | 54.2 | |||

| 40 – 49 | 162 | 33.8 | 98 | 20.4 | |||

| 50 \(\leq\)) | 67 | 14 | 22 | 4.6 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 39.8 ± 7.7 | 35.2 ± 6.8 | |||||

| 2 | Level of education | Read write | 16 | 3.3 | 36 | 7.5 | |

| Primary school | 106 | 22.1 | 125 | 26 | |||

| Intermediate school | 133 | 27.7 | 81 | 16.9 | |||

| Secondary school | 61 | 12.7 | 67 | 14 | |||

| Diploma | 21 | 4.4 | 37 | 7.7 | |||

| Bachelor | 116 | 24.2 | 111 | 23.1 | |||

| Higher Diploma | 6 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.3 | |||

| Master | 13 | 2.7 | 17 | 3.5 | |||

| Doctorate | 8 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 3 | Occupation of Household Head | Employee | 233 | 48.5 | |||

| Retired | 18 | 3.8 | |||||

| Free work | 229 | 47.7 | |||||

| 4 | Monthly income (Iraqi Dinar) | 300000 | 107 | 22.3 | |||

| 300000 – 600000 | 122 | 25.4 | |||||

| 601000 – 900000 | 103 | 21.5 | |||||

| 901000 – 1200000 | 65 | 13.5 | |||||

| 1201000 – 1500000 | 61 | 12.7 | |||||

| 1501000 + | 22 | 4.6 | |||||

| 5 | Number of children | 1 – 3 | 297 | 61.9 | |||

| 4 – 6 | 169 | 35.2 | |||||

| 7 + | 14 | 2.9 | |||||

| 6 | Child sex | Male | 240 | 50 | |||

| Female | 240 | 50 | |||||

| 7 |

Child Age

M±SD= 7±0.8 |

6 – 7 | 312 | 65 | |||

| 8 – 9 | 168 | 35 | |||||

| 8 | School Type | Public | 240 | 50 | |||

| Private | 240 | 50 | |||||

| 9 | Grade | First | 160 | 33.3 | |||

| Second | 160 | 33.3 | |||||

| Third | 160 | 33.3 | |||||

| F: Frequency, %: Percentage, M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation | |||||||

| List | Factors | M | SD | Assess. |

| 1 | Fear of negative judgment from others | 2.57 | 1.443 | Moderate |

| 2 | Fear of legal consequences (e.g., police involvement) | 2.90 | 1.562 | Moderate |

| 3 | Fear of my child getting injured | 3.97 | 1.269 | High |

| 4 | Fear of being unable to rescue my child if something happens | 3.74 | 1.439 | High |

| 5 | Fear of my child being harmed by someone (e.g., kidnapping) | 3.81 | 1.479 | High |

| 6 | Belief that boys/girls should not engage in this type of risky play | 3.69 | 1.395 | High |

| 7 | Fear that the play activity/situation is too challenging for my child | 3.59 | 1.319 | Moderate |

| 8 | My personality/prior experiences with similar activities | 3.15 | 1.298 | Moderate |

| 9 | Guilt that something unexpected/bad could happen to my child or others | 3.32 | 1.401 | Moderate |

| 10 | Fear that my child will face problems from engaging in the activity | 3.26 | 1.331 | Moderate |

| 11 | Cultural views that the play activity is inappropriate or unsafe | 3.31 | 1.291 | Moderate |

| 12 | Fear of long-term effects/consequences on my child | 3.35 | 1.285 | Moderate |

| 13 | Belief that my child’s personality would interfere | 3.19 | 1.405 | Moderate |

| 14 | Perception that play materials/situations are unsafe | 3.58 | 1.322 | Moderate |

| 15 | Influence of media reports about child injuries/abductions | 3.22 | 1.486 | Moderate |

| 16 | Belief that my child is too young to participate in this risky play | 3.55 | 1.342 | Moderate |

| 17 | Fear that the environment/activity is unfamiliar | 3.30 | 1.302 | Moderate |

| M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation Low= 1 – 2.33, Moderate= 2.34 – 3.67, High= 3.68 – 5 | ||||

| List | Sensory Environment | M | SD | Assess. |

| 1 | Putting on clothes (excluding socks/shoes/coat) | 3.06 | 1.238 | Moderate |

| 2 | Putting on socks and shoes | 3.37 | 1.204 | Moderate |

| 3 | Putting on a coat independently or with assistance | 3.14 | 1.201 | Moderate |

| 4 | Brushing teeth | 3.39 | 1.060 | Moderate |

| 5 | Bathing (excluding hair washing) | 2.83 | 1.270 | Moderate |

| 6 | Washing hair | 3.33 | 1.153 | Moderate |

| 7 | Brushing/combing hair | 3.33 | 1.233 | Moderate |

| 8 | Trimming fingernails/toenails | 3.25 | 1.202 | Moderate |

| 9 | Toileting (diaper changes or using the toilet) | 3.47 | 1.079 | Moderate |

| 10 | Sleeping | 3.48 | 1.141 | Moderate |

| 11 | Staying asleep through the night | 3.35 | 1.175 | Moderate |

| 12 | Eating | 3.26 | 1.077 | Moderate |

| 13 | Mealtime with family members | 3.55 | 1.099 | Moderate |

| 14 | Playing with siblings/children at home | 3.53 | 1.195 | Moderate |

| 15 | Playing with toys/objects | 3.21 | 1.061 | Moderate |

| M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation, Low= 1 – 2.33, Moderate= 2.34 – 3.67, High= 3.68 – 5 | ||||

| Pathway | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | Standardized Effect |

| Direct Effect (X \(\rightarrow\)) Y) | 0.2252 | 0.0752 | 2.9957 | 0.0029 | 0.0775 | .3730 | .1375 |

| X = SE (Predictor), Y = PT (Outcome), Mediators = EF, A, ER LLCI/ULCI = Lower and Upper Confidence Intervals | |||||||

Concerning parents’ age, the results indicate that both parents are predominantly concentrated in the 30–39 age range, with over half of fathers (54.2%) and nearly half of mothers (47.3%). This finding is consistent with the study by [10], which found that most parents were under 39 years old, with 88.5% in this age group, while the prevalence of mothers under 35 years was 92.4%. This finding contradicts the study by Saadoon and Ajil [11], which found a high percentage of mothers aged 35–45 years (63.1%) and fathers aged 37–46 years (71.6%). The findings indicate that mothers show a higher proportion in intermediate school (27.7%), while fathers are more frequently primary school graduates (26%). This finding is supported by the study of Minello and Blossfeld [12], which found that mothers had a higher proportion of intermediate school graduates (27.7%), while fathers were more frequently found among primary school graduates (26%). This highlights distinct trends in educational attainment between mothers and fathers in West Germany.

The study contradicts the study by Omar and Muttaleb [13], which found that the highest percentages of mothers and fathers were primary school graduates (39.2% and 36.1%), respectively. The findings showed that nearly half of household heads (48.5%) were employees. This finding is similar to the study by Hachim et al. [14], which found that approximately half of the study participants’ households were employers (49.3%). Income distribution highlights economic instability, with 47.7% earning \(\leq\)600,000 Iraqi Dinar monthly. This result contradicts the findings of a study conducted by Mohammed and Hatab [15], which found that around 46% of families had a monthly income of more than 900,000 ID. Family size trends toward smaller households, as 61.9% of families have 1–3 children. This finding aligns with the study by Shauq [16], which found that most of the studied mothers had 1–4 children (68.2%). Sex distribution is perfectly balanced (50% male, 50% female), and this finding aligns with the study by Al-Jubouri [17], which found that sex distribution was balanced among male and female students due to the random selection of study participants (50% each). For child age, the results revealed that most children (65%) fall within the 6–7 age range. This finding is supported by studies [18, 19], which found that most children were in the 6–8 years age range (72%). School enrollment shows equitable representation across public and private institutions (50% each). This finding is supported by the study of Shahzadi and Iqbal [20], who conducted a comparative study of public and private primary schools with regard to effective teaching activities and outcomes. They found an equal proportion of public and private institutions (50%). The research emphasized the importance of balanced representation in educational studies. Grade distribution is uniform, with equal proportions in first, second, and third grades (33.3% each). This finding contradicts the study by Alarawi et al. [21], who found equal grade distribution in the fourth, fifth, and sixth stages (33.3%).

The study indicates that parents’ tolerance for risky play is significantly influenced by various fears and beliefs, with certain concerns standing out as particularly strong. The highest-rated factors contributing to reluctance include fear of child injury, fear of harm by others such as kidnapping, fear of being unable to rescue the child in case of an emergency, and gender-related beliefs about risky play. These results suggest that safety concerns, protective instincts, and societal norms play a crucial role in shaping parental attitudes. This finding is supported by the study by Oliver et al. [22], who found that “risk of injury” was a significant concern for parents in Britain, often leading them to restrict adventurous play despite recognizing its benefits. Jelleyman et al. [23] also identified “stranger danger” as a concern leading to restricted independent mobility and outdoor play opportunities.

The study results reveal that approximately half of the participants (49.6%) have a moderate level of tolerance. This finding is supported by the study of Jerebine et al. [24], which found that 52% of parents had a moderate level of tolerance for risky play, indicating that approximately half of parents were positive about their children’s engagement with risk. The study indicates that mealtime with family members (M=3.55, SD=1.099) and playing with siblings/children at home (M=3.53, SD=1.195) were rated slightly higher for sensory activity. This finding is supported by Powell et al. [25], who observed that children aged 6 to 10 exhibited fewer food refusals and were easier to feed when mothers ate with them and consumed the same food, suggesting that a structured mealtime environment positively influences children’s eating behavior. This supports the notion that a calm and structured sensory environment during mealtimes can encourage positive child behaviors. The finding also aligns with a study by Wade [26], who found that sensory play combined with repeated exposure to new foods improved food acceptance among preschoolers. This highlights the importance of sensory experiences in shaping children’s responses to various activities, including mealtime and play.

The study indicates that the sensory environment (SE) has a significant direct effect on parents’ tolerance (PT) (\(\beta = 0.2252\), \(p = 0.0029\)), suggesting that a more accommodating sensory environment positively influences parental tolerance. This finding is supported by Little and Akdemir et al. [27], who found that environmental characteristics—especially sensory ones such as noise levels, spatial layout, and physical comfort—had a measurable impact on parental tolerance for risky activities. Moore and Lynch [28] also found that calmer, sensory-regulated environments promoted greater parental engagement and less restrictive supervision.

Less than half of parents demonstrated a moderate level of tolerance for risky play. The sensory environment emerged as a crucial factor, having a significant direct positive effect on parental tolerance for risky play. A substantial majority of children were found to experience a moderate sensory environment. When combined with the finding that a more accommodating sensory environment increases parental tolerance, this highlights a potential area for intervention.

Interventions and educational materials should be designed with varying literacy levels and educational backgrounds in mind. This will ensure that information on risky play and sensory environments is accessible and impactful for both parents. Programs could focus on strategies to gradually increase their comfort with supervised risky play, emphasizing its developmental benefits. Highlighting the link between a positive sensory environment and increased tolerance could be a key component of such programs. Future research should explore the causal mechanisms between sensory environments and parental tolerance through longitudinal or interventional studies. Investigating specific elements of the sensory environment that are most impactful would also be beneficial.

Hansen Sandseter EB. Categorising risky play—how can we identify risk‐taking in children’s play?. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal. 2007 Jun 1;15(2):237-52.

Yamada M, Arai H. Self-management group exercise extends healthy life expectancy in frail community-dwelling older adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017 May;14(5):531.

Gill T. Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities. Riba Publishing; 2021 Mar 3.

Niehues AN, Bundy A, Broom A, Tranter P. Parents’ perceptions of risk and the influence on children’s everyday activities. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015 Mar;24:809-20.

Dudek M. Architecture of Schools: The New Learning Environments. Routledge; 2012 Sep 10.

Moore A, Lynch H. Accessibility and usability of playground environments for children under 12: A scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015 Sep 3;22(5):331-44.

Hussein AN. Perceived social support and psychological well-being among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder in Al-Nasiriyah city. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology. 2021;25(4):10117-26.

Brussoni M, Olsen LL, Pike I, Sleet DA. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012 Sep;9(9):3134-48.

Sobel D. Childhood and Nature: Design Principles for Educators. Stenhouse Publishers. 2008.

de Carvalho PH, Machado RA, de Almeida Reis SR, Martelli DR, Dias VO, Júnior HM. Parental age is related to the occurrence of cleft lip and palate in Brazilian populations. Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences. 2016;15(2):167-70.

Saadoon MK, Ajil ZW. Evaluation of parents’ performance towards care of children with hearing disorders. Journal of Advance Multidisciplinary Research. 2024 Feb 21;3(1):46-50.

Minello A, Blossfeld HP. From parents to children: the impact of mothers’ and fathers’ educational attainments on those of their sons and daughters in West Germany. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2017 Jul 4;38(5):686-704.

Omar HK, Muttaleb WM. Parents knowledge of oral health of children with cancer. Iraqi National Journal of Nursing Specialties. 2024 Jun 30;37(1):132-9.

Hachim SN, Muttaleb WM, Mahmood SA. Assessment of mothers knowledge towards care of children with Erb’s palsy. age.;1(5):39.

Mohammed AQ, Hatab KM. Quality of life of children age from (8-lessthan13) years with acute lymphocytic leukemia undergoing chemotherapy. Iraqi National Journal of Nursing Specialties. 2022;35(1).

Shauq A. Burden of mothers’ care for children with colostomy at Baghdad medical city teaching hospital. Iraqi National Journal of Nursing Specialties. 2015 Dec 30;28(2):8-23.

AL-jubouri SM. Assessment of psychological adjustment among preparatory school students. Iraqi National Journal of Nursing Specialties. 2022;35(1).

Maala E. Body satisfaction and depression symptoms among children with precocious puberty in Baghdad City. Iraqi National Journal of Nursing Specialties. 2019 Jun 30;32(1):39-46.

Mohammed QQ. School refusal behavior of primary first class pupils in Baghdad. Journal Of Educational and Psychological Researches. 2016 Jul 3;13(50):378-88.

Shahzadi M, Iqbal H. A comparative study of public and private primary schools with perspective of practice of effective teaching activities and outcomes. 2023.Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/107013516/A_Comparative_Study_of_Public_and_Private_Primary_Schools_with_Perspective_of_Practice_of_Effective_Teaching_Activities_and_Outcomes.

Alarawi RM, Lane SJ, Sharp JL, Hepburn S, Bundy A. Navigating children’s risky play: A comparative analysis of Saudi mothers and fathers. OTJR: Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2025 Jan 15:15394492241311004.

Oliver BE, Nesbit RJ, McCloy R, Harvey K, Dodd HF. Parent perceived barriers and facilitators of children’s adventurous play in Britain: a framework analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022 Apr 1;22(1):636.

Jelleyman C, McPhee J, Brussoni M, Bundy A, Duncan S. A cross-sectional description of parental perceptions and practices related to risky play and independent mobility in children: the New Zealand state of play survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019 Jan;16(2):262.

Jerebine A, Mohebbi M, Lander N, Eyre EL, Duncan MJ, Barnett LM. Playing it safe: the relationship between parent attitudes to risk and injury, and children’s adventurous play and physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2024 Jan 1;70:102536.

Powell F, Farrow C, Meyer C, Haycraft E. The importance of mealtime structure for reducing child food fussiness. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2017 Apr;13(2):e12296.

Wade SL. Commentary: Computer-based interventions in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004 Jun 1;29(4):269-72.

Akdemir K, Banko-Bal Ç, Sevimli-Celik S. Giving children permission for risky play: Parental variables and parenting styles. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education. 2023 Dec;26(3):289-306.

Moore A, Lynch H. Accessibility and usability of playground environments for children under 12: A scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015 Sep 3;22(5):331-44.